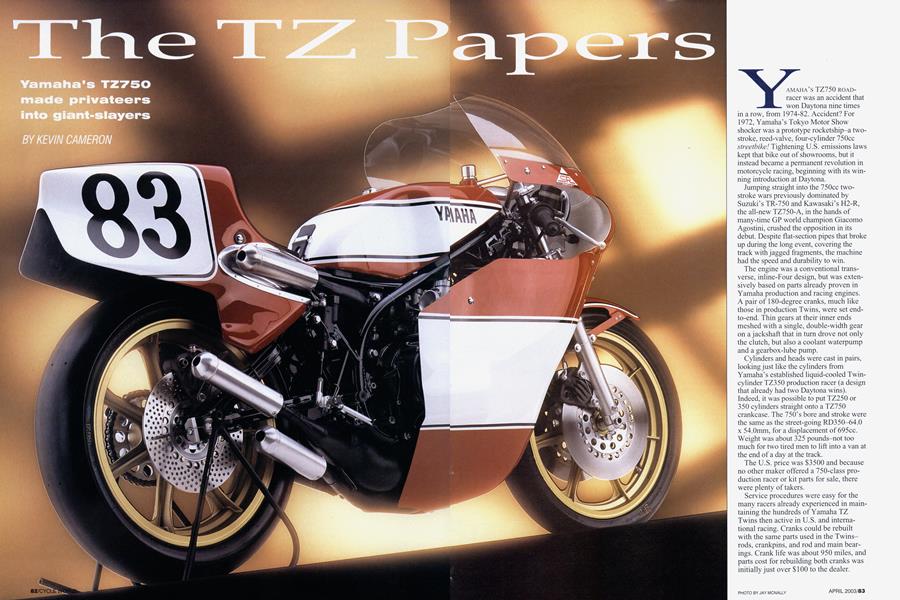

The TZ P apers

Yamaha's TZ750 made privateeers into giant-slayers

KEVIN CAMERON

YAMAHA’S TZ750 ROADracer was an accident that won Daytona nine times in a row, from 1974-82. Accident? For 1972, Yamaha’s Tokyo Motor Show shocker was a prototype rocketship-a twostroke, reed-valve, four-cylinder 750cc streetbike! Tightening U.S. emissions laws kept that bike out of showrooms, but it instead became a permanent revolution in motorcycle racing, beginning with its winning introduction at Daytona.

Jumping straight into the 750cc twostroke wars previously dominated by Suzuki’s TR-750 and Kawasaki’s H2-R, the all-new TZ750-A, in the hands of manyftime GP world champion Giacomo Agostini, crushed the opposition in its debut. Despite flat-section pipes that broke up during the long event, covering the track with jagged fragments, the machine had the speed and durability to win.

The engine was a conventional transverse, inline-Four design, but was extensively based on parts already proven in Yamaha production and racing engines.

A pair of 180-degree cranks, much like those in production Twins, were set endto-end. Thin gears at their inner ends meshed with a single, double-width gear on a jackshaft that in turn drove not only the clutch, but also a coolant waterpump and a gearbox-lube pump.

Cylinders and heads were cast in pairs, looking just like the cylinders from Yamaha’s established liquid-cooled Twincylinder TZ350 production racer (a design that already had two Daytona wins). Indeed, it was possible to put TZ250 or 350 cylinders straight onto a TZ750 crankcase. The 750’s bore and stroke were the same as the street-going RD350-64.0 x 54.0mm, for a displacement of 695cc. Weight was about 325 pounds-not too much for two tired men to lift into a van at the end of a day at the track.

The U.S. price was $3500 and because no other maker offered a 750-class production racer or kit parts for sale, there were plenty of takers.

Service procedures were easy for the many racers already experienced in maintaining the hundreds of Yamaha TZ Twins then active in U.S. and international racing. Cranks could be rebuilt with the same parts used in the Twinsrods, crankpins, and rod and main bearings. Crank life was about 950 miles, and parts cost for rebuilding both cranks was initially just over $100 to the dealer.

When the 750cc Kawasaki and Suzuki two-stroke Triples burst onto the U.S. roadracing scene in 1972, their wobbling, tire-shredding ways established their riders as supermen. The twin-shock TZ750-A was initially not much better. A crisis came at Talladega, where Yamaha factory team A-models weaved so violently at 170 mph that they threw their riders’ feet off the footpegs.

Privateer Dave Smith sat in his lawn chair after first practice, white-faced and visibly shaking. The immediate problem was a displaced wire clip in the fork. The work required to find the problem and restore chassis stability caused U.S. Yamaha team boss Kel Carruthers to make a prophetic utterance that reverberates to this day: “From now on, we’ll have to put as much preparation into the chassis as the engine-if not more.”

The great strength of readily available equipment is that it puts multiple minds to work on a problem. The many TZ750 owners, all trying to make their bikes handle better, soon produced results. The long-travel suspension revolution was ready to leap from motocross to roadracing. Carruthers made his own single-shock conversion of an A-model, and other builders extended suspension travel in other ways. The result was that bump energy could now be absorbed more gradually, over a longer distance. The payoff was less upset to the machine. The frightening weaves and wobbles of 1974 were, in these modified bikes, largely tamed in 1975. That was the year of the “full kit,” which with 66.4mm-bore pistons, cylinders and heads made the engine into a full 748cc. Breakage of gears, cylinder studs and nuts was corrected.

Individuals replaced the crack-prone flat exhaust pipes with a variety of hand-built substitutes. The enduring solution was Carruthers’ three-under/one-over system. Three normal round-section pipes ran back under the chassis, while the fourth pipe snaked under the left side of the engine, up across the ignition, then crossed under the tank, behind the carbs, to exit under the rider’s right thigh. This combined cornering clearance with uncompromised pipe performance.

For 1976, Yamaha rolled out the official factory solution-the very compact and updated monoshock OW-31. Looking like a plump 250 with Carruthers-style pipes, the OW was tremendously fast and its handling was vastly improved. Today, it’s considered normal to wheelie leaned over exiting comers, but Steve Baker did it first on the OW in the Transatlantic Match Races that year. Chassis confidence and 130 horsepower had made this inevitable. By 1978, all the top riders were doing it.

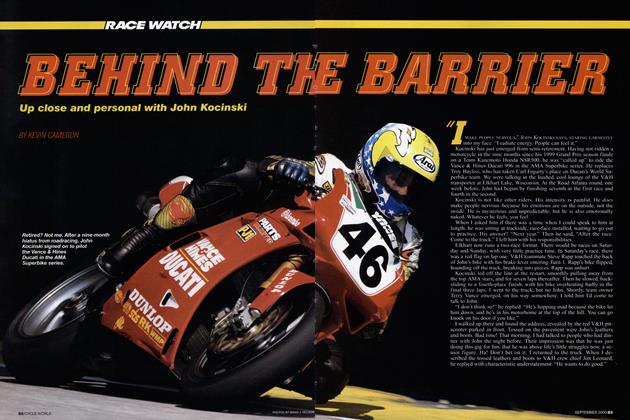

Strarigc Case of the Variishing TZ750

In 1979, Steve McLaughlin, one of the strongest privateers of the TZ era, and his mechanic had a little disagreement about payment. Money was demanded, McLaughlin refused to pay and when he showed up at Laguna Seca for practice, van and racebike were gone, his mechanic filing a lien against the bike. “McLaughlin just wrote the bike off because it was barely worth the lien amount, which was $8000,” says Jeff Palhegyi, the man who tracked down and restored the bike to its glorious condition. The TZ sat in a Redondo Beach, California, garage for 20 years corroding away in the salty air.

“When I found the bike,” says Palhegyi, “it was a complete basketcase, just rotting. It was so bad that when I brought it back to my shop for restoration, everybody laughed at me.” McLaughlin’s old wrench had an inflated opinion of the TZ’s value. He wanted a cool $25,000. “After a year, we finally made a deal—I traded him a brand-new ’01 KTM Duke,” says Palhegyi. Ironically, the Duke was worth right at the original $8000 lien amount...

The 1977 TZ750-D was a productionized OW. Its great leap forward in handling restored the self-confidence many riders had lost on the A-model. This was a tool that any good rider could use-the definitive TZ750.

Kenny Roberts never liked the big TZ-especially in comparison with the growing sophistication of the 500cc Grand Prix bikes he was riding in Europe. The 750 had too much of everything and was like trying to guide an explosion. At Daytona, Roberts looked annoyed on the 750, flinging it over hard in the chicane, straight into tire chatter, then lifting and flicking over to chatter just as hard on the other side-exhausting but effective.

A glance reveals why. Compared with a modem bike, the TZ has almost no chassis. All that holds it together is the same two loops of thinwall steel pipe with a swingarm that Rex McCandiess created for Norton back in 1950-but with 140 bhp going through it all. The basic TZ chassis had been designed when skin ny Dunlop Triangulars were king, but by 1976 it was being forced to han die the grip of wide slick tires. It couldn't do it. The TZ tube frame wound up like a spring and let go like a catapult. Its chatter was textbook stuff-everything flexing and shaking.

When you bend steel repeatedly this way, it cracks. We learned where to look-just below the steering-head gusset on the right-hand downtube, and on the coil and footpeg brackets. If you found no cracks, your rider wasn’t riding hard enough.

Despite its problems, the TZ750 was a huge leap forward in the design of high-power motorcycles. Top privateers on TZ750s regularly beat factory riders on the unobtainable 750s of other makes. In 1974,1 worked with 19-year-old rider Jim Evans, who was able to put his Boston Cyclessponsored TZ third at Talladega and Ontario. Ahead were two factory Yamahas. Behind him were all other factory bikes. Not bad for something anyone could buy.

Worshippers of vintage four-strokes sneeringly call the time of Yamaha TZ750 dominance “The Forgotten Era,” but to me, what was forgotten then was the traditional huge gap between factory and privateer. Was it a golden age in the 1960s, when a single MV Agusta Four won every race by a huge margin from a field of private Singles? Yamaha’s equalizer closed that gap to zero. Privateer Dale Singleton won Daytona twice on TZ750s. Now imagine a privateer of today, on a bike bought for the price of a cheap car, beating factory AMA Pros on the current $800,000 Superbikes. “The Forgotten Era” was the era of the privateer.

Other privateers-Mike Baldwin, Nick Richichi, Rich Schlachter, Skip Aksland, Miles Baldwin and Greg Smrz-won races on TZ750s against factory opposition.

Mike Baldwin beat them all in 1978 at the Canadian F-750 round at Mosport Park-Roberts, Baker and Yvon DuHamel included-on his self-tuned Yamaha TZ750-D. This era came to an end in 1983 when Miles Baldwin (no relation to Mike) and his rough-looking, self-tuned TZ “locomotive” just missed taking the AMA Formula One roadrace title from Honda’s official team. It had been an exciting time when a “man in a van with a plan” could still make waves.

American 750cc racing had been glamorous and fast, and U.S.-style 200-mile races sprang up in Europe beginning in 1972. Formula 750, as it was called, soon came close to displacing 500cc GP racing as the pinnacle of sport, but it didn’t last. Despite factory participation by Suzuki and Kawasaki, world-class TZ750s with good riders were everywhere in the late 1970s, and won too often. A decision was made to end F-750 and concentrate on 500cc GP.

Therefore, when Kenny Roberts raced Daytona in 1982, it was aboard a sophisticated disc-valve 500cc GP bike. The crude TZ750 had been technologically left behind. Honda fielded its pioneering giant four-stroke, the lOOOcc V-Four FWS (father of all subsequent Honda V-Fours). As backup, Yamaha assembled from surplus parts an “obsolete” OW-31 for Graeme Crosby to ride. Kenny’s 500 seized, leaving Crosby to cruise his parts-bike to yet another TZ750 victory as the fast Hondas struggled with tire troubles.

A year later, TZ75Os looked tired and obsolete, even to me. They were.

The TZ750 succeeded because it employed proven ele ments in tested ways. Porting was late-i 960s. Mechanically, the engine was extensively based on parts proven in earlier Twins. Its reed intake valves came from motocross. One of the engineers involved was Masakazu Shiohara-designer of Yamaha's current YZR-M1 four-stroke MotoGP engine.

What made this all work was Yamaha's experience in pro ducing and distributing over-the-counter racing parts, begin ning with the 250cc TD1 of 1962. Yamaha's catalog racer and parts were usually good enough to beat the factory-only equipment of other makers.

TZ75Os were good, but not perfect. Early ones broke the three-spoke gears in the gearbox. Crank gears came loose until we learned to double the torque spec in the manual. Coils and plug caps that ran forever on 250s fell victim to the 750's different vibration. Ignition triggers fried from the heat of the crossover exhaust pipe. The chrome bores of the aluminum cylinders lasted about 600 miles, after which we had them Nikasil-plated by Mahie for about $125 a hole. Later, as privateers ran their bikes harder, flywheel discs cracked, opening up like 1 1,000-rpm brake shoes and wreck ing the $1000 crankcase. We laugh at these prices today, when a crankcase for a GP bike costs as much as a house.

As the last privateers gave up their TZ75Os in 1983-84, the choice was either a Honda RS500 two-stroke Triple at $27,000, or trying to wheedle last year's factory four-stroke racebike of some kind. How about building your own four stroke? Some tried, but the result was the infamous two-level AMA Nationals of the 1980s. After the start, the factory four-strokes would howl past like the MVs of yesteryear. Thirty seconds to a minute later came the “smoking junk”-one factory team manager’s term for the struggling products of backyard ingenuity.

Without available, affordable racing equipment to sustain it, racing could go only two ways-to production classes, or to the factory professionalism of Superbike.

The TZ750, for a time, gave clever people who were willing to work the opportunity to win at roadracing’s highest level, against the best the factory teams had to offer. Try to imagine that happening today.