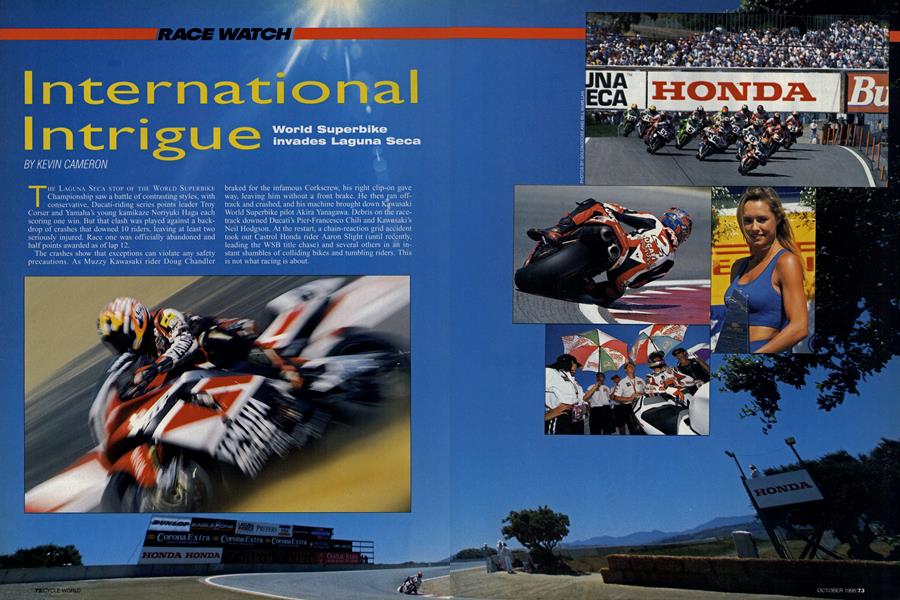

International Intrigue

RACE WATCH

World Superbike invades Laguna Seca

KEVIN CAMERON

THE LAGUNA SECA STOP OF THE WORLD SUPERBIKE Championship saw a battle of contrasting styles, with conservative, Ducati-riding series points leader Troy Corser and Yamaha's young kamikaze Noriyuki Haga each scoring one win. But that clash was played against a backdrop of crashes that downed 10 riders, leaving at least two seriously injured. Race one was officially abandoned and half points awarded as of lap 12.

The crashes show that exceptions can violate any safety precautions. As Muzzy Kawasaki rider Doug Chandler braked for the infamous Corkscrew, his right clip-on gave way, leaving him without a front brake. 1-le then ian offtrack and crashed, and his machine brought down K*wasaki World Superbike pilot Akira Yanagawa. Debris on the race track downed I)ucati's Pier-Francesco Chili and Kawnsaki's Neil Hodgson. At the restart, a chain-reaction grid accident took out C'astrol Honda rider Aaron Slight (until redently, leading the WSB title chase) and several others in an in stant shambles of colliding bikes and tumbling riders. This is not what racing is about.

Haga, who had himself crashed out in the first go-around, rode with wild brilliance in the second leg to over come a craftsman-like attack by Cors er. Haga's intensity was breathtaking. Taking broad, sweeping lines, snapping loose and weaving, running wide onto the rumble strips, raising off-track dust, the chunky, baby-faced 23-yearold development rider showed what his YZF75O's chassis could do at its limit.

Ben Bostrom, the sole remaining American Honda rider after Miguel Duhamel's leg-breaking crash at Loudon, New Hampshire, won a race-long struggle with more experi enced men to finish third. Chili and Suzuki's James Whitham completed the first five.

That's the news. Now for the back ground.

World Superbike has fine prospects after 10 years of existence. The recent alliance with Octagon fits WSB into a vertically integrated scheme of sports development, advertising and distribu tion. With four exceptions (Kawasaki in `93 and Honda in `88, `89 and `97), WSB has been all Ducati, with second billing for whoever wanted to make the effort. Competition and factory in terest have intensified as the 916 has approached the end of its viability.

At the present, WSB is an open se ries that belongs to no one, and that makes it fascinating. Ducati's long-term experience and professionalism have kept it near the top, while the remark able Haga has made the notionally ob solete and soon-to-be-replaced Yamaha YZF75O competitive. Honda's RC45, too, has had wins this year with Aaron Slight and Texan Cohn Edwards. From all this has come a clear perception that there is no longer any single way to win WSB races. All three general types of machines-inline-Fours, Ducati's V Twin and the Honda V-Four-have won races this year.

Here is how it looks to me right now: Traditional inline-Fours like the Kawasaki and Yamaha have slightly longer wheelbases and lower centersof-gravity than the Honda. They steer during corner exits by smooth wheelspin, terminated controllably by knocking the throttle. Then, their rear tires hook up with a little shiver and the bikes shoot off the corner. The Ducati seldom spins because its weight is carried a bit farther back. It hooks up and accelerates, but there's a rub: With less weight on the front wheel, the Ducati will push, making it hard to hold line. This forces riders like Chili to avoid acceleration by substituting high corner speed. He rushes into flat corners like a 250cc Grand Prix rider, and must delay throttle application until past the apex. Once the machine is lifting and the rear tire has surplus grip, acceleration is strong and adequate. But the spin steering inline-Fours have no clear ad vantage either, for once the tire spins, that's all the throttle it will accept. They steer, but they pay for the privi lege with less acceleration.

Honda has its own special category. With its engine set somewhat higher and farther back than the inline-Fours (I have measured this), the RC45 transfers more weight to the rear wheel during acceleration. Instead of spinning smoothly and controllably, it tends to hook up-especially on Michelins, as used by the WSB team. Making the Honda steer, then, takes a combination of rider artistry and spe cialized tire treatment; you can see riders pull themselves as far forward as possible to make these bikes hold line at corner exits. When the bike spin-steers, it does so in a twitchy way, because the chassis can't quite decide whether to spin or hook up.

The choice here is the old one be tween performance and handling. Per formance in this case is off-corner acceleration. Handling is whether or not that acceleration is steerable. But unsteerable acceleration is as useless as acceleration-less steering. So the Kawasakis spin but they steer, while the Hondas hook up but are twitchy-and they push. As Miguel Duhamel and `97 WSB champ John Kocinski have shown, they can be made to spin-steer, but forget everything you thought you knew when you begin to learn how. Finally, the Ducatis accelerate like noth ing else, but they don't spin-steer and they will push.

It all comes down to a multitude of little tweaks and Band-Aids worked out in practice. Whoever hits the day's best compromise of acceleration and steering is in with a chance. Set-up experience counts. As one team man ager put it, "You can't use engineers at trackside. You need racing people for that-engineers know too much about what's impossible."

Think of the tires' angled shoulders as parts of two rolling cones. If the two cones have the right angles, the bike will tend to steer itself through a cor ner. If one is off a bit, it will try to go straight even though it's leaned over, and the rider has to make up the differ ence. Add to that the fact that the tires are flexible, fiber-reinforced bags; at one lean angle, they can act one way, and yet when leaned over a few more degrees, their characteristics can change completely. Get it all right-rim width, tire contour, tire carcass con struction, inflation pressure-and you have something to work with in mak ing all the other choices-damping, springing and machine attitude.

This is not engineering in the for mal sense of applied science. It is what I like to call "vending machine kicking." Rolling a new bike onto the racetrack for the first time is like putting your dollar into the Coke ma chine and not getting a Coke. Nothing works. The bike goes around, but the times are disappointing. The rider feels insecure, the bike is unpre dictable; it pushes, won't turn-in or chatters. Take your pick of a menu of problems. Experienced people know where and how hard to kick the vend ing machine. But some days, they kick and kick and still don't get a cool, refreshing drink.

Therefore, I believe that handling is piling up questions against a road block of hard-to-solve problems. It needs a big idea so that motorcycle performance can take a leap forward. Everyone is getting about the same performance from stunningly different combinations of ingredients.

Ready for some relief? Let's talk about the known world: engines. Be lievable rear-wheel horsepower figures are in the mid-150s now, with crank shaft horsepower 5-10 percent above that. The Hondas are acknowledged to have some extra top-end power, but getting off corners doesn't benefit from that. Some wildly inflated figures have been bandied about, but as one of my former riders put it, that's measured "at the advertiser's penpoint."

If a given engine is making 160 crankshaft bhp at 13,800 rpm, that means the stroke-averaged net com bustion pressure is a hefty 200 psi-a figure that compares well with the best there is. But 13,800 rpm, with the roughly 45mm strokes common in four-cylinder Superbike engines, translates to a piston speed of 4100 feet per minute. This was state-of-theart in 1956, but Ducati, with its much longer 66mm stroke, develops peak power at 10,500-10,800 rpm, for a piston speed of close to 4700 feet per minute. Both Fours and Twins are rev limited higher than these figures, but that mainly provides mechanical safety and overrev capability for situa tions in which the rider can go faster by carrying a gear rather than shifting.

If the Fours could be pushed to the higher piston speed, yet retain the same combustion pressure, they would make more than 180 bhp at al most 16,000 rpm. Since power re quirement goes up roughly as the cube of the speed (to go twice as fast, you'd need eight times the power), this potential extra 20 bhp would con fer an extra 7 or so mph on top.

So why not rev `em up? Mass-pro duction engines lack the rigidity of race engines, and production camand valve-drive arrangements also have lower limitations. As an example of the differences, consider this: Cur rent purpose-built auto-racing engines often use valve accelerations so vio lent that idling is impossible; even a few seconds of idle wipes out cams and tappets because there's too little velocity to form an oil film that can carry the pressure. By contrast, it's normal for a Superbike engine to warm up at idle, which you can hear at any of these races. Big difference.

What is the future of World Super bike? On the one hand, technology beckons. Engineers would love to build 200-bhp, pneumatic-valve, ultra short-stroke engines, but no one could afford them. Plus, Superbikes must begin life on the street, where the EPA, TUV and other regulatory agen cies are king. The alternative? Right now, the All-Japan Superbike series is permitting 900 and 1000cc production bikes, with lesser modifications, to compete with traditional 750cc Fours and 1000cc Twins. Something like this is under consideration by the FIM for World Superbike, and hints of it are present in U.S. forms of racing such as AMA Formula Xtreme.

I love technology, but racing has to come first. When it takes the combined wealth of all five factories to build one fabulous machine, racing is over. Every year, fewer privateers remain in WSB, so I'd like to see the 900/1000 idea implemented. Besides, the really interesting problems are not with en gines, but with chassis and suspension. Anyone with a workable suspension innovation will move ahead, no matter what kind of engine he's using.

World Superbike began as and re mains a repository for riders whose best years were spent in other series. There are exceptions, but this pattern remains visible. We saw the same thing in U.S. Superbike. Initially, some theorized that older, more expe rienced men were needed to master the complexities of blending street chassis with race engines. When Fred die Spencer hit the scene, the old-man theory was blown quickly into the weeds where it belonged. This is tem pered by the difficulty of set-up. Ex GP rider Chil4, 34, is skilled at this and can still show his heels to younger men who have to fight their own bikes as well as his.

Currently, you hear muttering to the effect that, "Haga won't be so fast once he's crashed really hard." This is sour grapes. Haga practices a religion of speed. His mind is unclouded by nonsense about investments, life in Monaco and which speedboat to buy. For the moment, he wants to win races. What a novel concept.

But maybe the factories prefer skilled-but-conservative riders? After all, a pile of trashed factory Superbikes costs millions. Better to have men who always bring `em back whole? That's not how it works. The factories are steadily getting more se rious about WSB, and there is real pressure to win. Yes, it was a nice, light-hearted, sportsmanlike series not so many years back-a breath of fresh air compared with GP racing's grim ness. But now that the privateers are all but squeezed out, and now that the factories have to cut their financial fu tures out of each other, it's not so frothy any more. The Greeks said to their soldiers, "Return with your shield, or upon it." The performance clauses in factory contracts surely sound much the same. Not so long ago, a rider could choose to lay low at tracks he considered extra-risky. Now, doing that will earn him a recitation of the Articles of War, if not worse. Racing is fun when the lap times come easily, not so much fun if it's just a job. Haga is lucky, and we are lucky to have him.

The upshot is that WSB contains a number of fine riders and machines of contrasting character. This makes it less likely that only one of them will stum ble into a killer set-up on a given day, and split. The result is often brilliant racing of the kind we saw at Laguna Seca between Haga and Corser-one on the supposedly underpowered, aged Yamaha, the other on the underpow ered, aged Ducati. Couple this good cast of characters with excellent busi ness prospects and you have a fine, if increasingly serious, race series.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUp In Smoke

October 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsLove the One You're With

October 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWise Cracks

October 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1998 -

Roundup

Roundup1999 Triumphs Ready To Roll

October 1998 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupGettin' High On the Hog!

October 1998 By Wendy F. Black