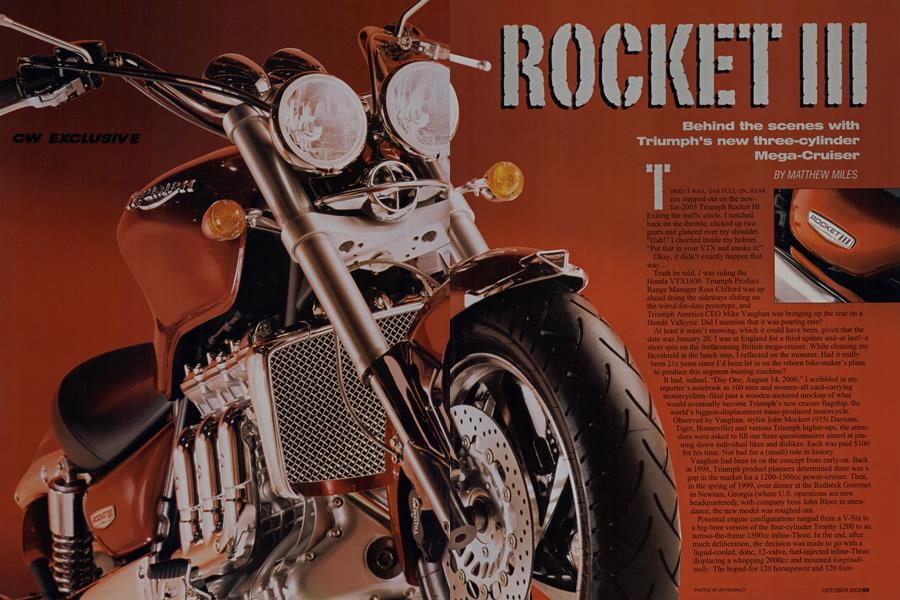

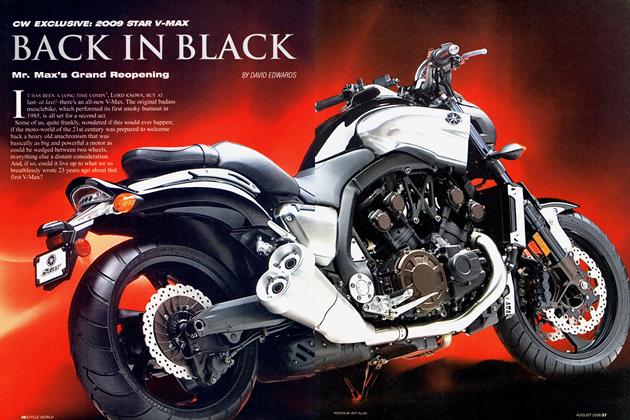

CW EXCLUSIVE

ROCKET III

Behind the scenes with Triumph's new three-cylinder Mega-Cruiser

MATTHEW MILES

THERE I WAS, GAS FULL ON, REAR tire stepped out on the newfor-2005 Triumph Rocket III. Exiting the traffic circle, I notched back on the throttle, clicked up two gears and glanced over my shoulder. “Hah!” I chortled inside my helmet. “Put that in your VTX and smoke it!” Okay, it didn’t exactly happen that

way...

Truth be told, I was riding the Honda VTX 1800. Triumph Product Range Manager Ross Clifford was up ahead doing the sideways sliding on the wired-for-data prototype, and

Triumph America CEO Mike Vaughan was bringing up the rear on a Honda Valkyrie. Did I mention that it was pouring rain?

At least it wasn’t snowing, which it could have been, given that the date was January 20.1 was in England for a third update and-at last!-a short spin on the forthcoming British mega-cruiser. While cleaning my faceshield at the lunch stop, I reflected on the moment. Had it really been 202 years since I’d been let in on the reborn bike-maker’s plans to produce this segment-busting machine?

It had, indeed. “Day One, August 14, 2000,” I scribbled in my reporter’s notebook as 100 men and women-all card-carrying motorcyclists-filed past a wooden-motored mockup of what would eventually become Triumph’s new cruiser flagship, the world’s biggest-displacement mass-produced motorcycle. Observed by Vaughan, stylist John Mockett (955i Daytona, Tiger, Bonneville) and various Triumph higher-ups, the attendees were asked to fill out three questionnaires aimed at pinning down individual likes and dislikes. Each was paid $100 for his time. Not bad for a (small) role in history.

Vaughan had been in on the concept from early on. Back in 1998, Triumph product planners determined there was a gap in the market for a 1200-15OOcc power-cruiser. Then, in the spring of 1999, over dinner at the Redneck Gourmet in Newnan, Georgia (where U.S. operations are now headquartered), with company boss John Bloor in attendance, the new model was roughed out.

Potential engine configurations ranged from a V-Six to a big-bore version of the four-cylinder Trophy 1200 to an across-the-frame 1500cc inline-Three. In the end, after much deliberation, the decision was made to go with a liquid-cooled, dohc, 12-valve, fuel-injected inline-Three displacing a whopping 2000cc and mounted longitudinally. The hoped-for 120 horsepower and 120 footpounds of torque would be transferred to a massive 240/50-16 rear tire via shaft final drive.

Employed as a stressed member of the chassis, the all-new engine would be hung from a steel-backbone frame set off by an inverted fork, twin shocks and triple-disc brakes. Dual headlights from the Speed Triple nakedbike would add a distinctive styling element (not to mention a familial resemblance), with a swept-back handlebar, dished seat -—^

and forward-mounted footpegs pro\

viding the sought-after cruiser \

ergonomics. X

When Vaughan made his pitch to \

Bloor, the bazooka-piped \

VTX1800 hadn’t yet been intro-

duced. Ditto the Harley-

Davidson V-Rod or Yamaha Road

Star Warrior. So, for all intents and

purposes, the competition comprised two bikes: the

Valkyrie and Yamaha’s 15-year-old V-Max. At 1198cc,

the V-Max didn’t present any real concerns, but what if, a

rumored, Honda upped the Valkyrie’s displacement from

1520cc to the 1832cc of the Gold Wing? If

Triumph’s Triple came to market in 2003, as

planned, it would have less than a 200cc JÊÊM

advantage over the pumped-up flat-Six.

Out came the calculators. .9

Displacement

was increased to

liters, or 140 cubic inches. It was estimated the bigger motor would produce a staggerggp* ing 140 horsepower and nearly 150 foot-pounds of torque! At just 2000 rpm, it would make four times as many foot-pounds as a V-Max. At 2500 rpm, it would produce double the grunt of a Valkyrie. “Lots of low-end power,” a senior engineer promised. “Power, power, power!”

The Triumph factory in Hinckley, Leicestershire, is smack in the middle of a busy industrial park. Unlike Ducati, which makes its presence known in Bologna with giant wall murals of its products, or Milwaukee-based HarleyDavidson with its character-rich brickwork and neighboring breweries, Bloor’s nondescript tilt-up has all the allure of a wet sock. To unknowing passersby, it could warehouse cleaning products.

Inside, however, it’s a completely different story. The seemingly ever-expanding facilities are spotless, expertly organized and furnished with up-to-the-minute machinery and tooling.

Twenty people were assigned to the project. Nine worked on the engine, another nine on the chassis, and two more on styling. Despite all this manpower, in February,

2002, Vaughan telephoned to inform me that the project was six months behind schedule. The bike might not go on sale until 2004.

Worse, British tabloid Motor Cycle News had just published spy photographs of a prototype, and Bloor was hell-bent on finding the leak. 3

One month later, the factory suffered what initially appeared to be a devastating fire. The overnight blaze was confined to the centermost portion of the factory, specifically bike assembly, the mold shop and powdercoating. The high-tech paint booth was spared, along with engine machining and assembly.

“We lost about 200 bikes,” former Managing Director Karl Wharton explained as he led me through the charred debris. “But we were back up and running more or less as normal within a day.”

With the cleanup ongoing, our meeting was moved to one of several portable offices set up in the parking lot. A parts cart was wheeled out with a crankshaft, connecting rod, piston and clutch. All appeared as if they belonged in a car, not a motorcycle. I needed both hands to hoist the clutch. The crankshaft weighs 39 pounds, 1 pound less than a VTX1800 crank. The pistons are the same size as the slugs that dance up and down in the cylinders of a Dodge Viper. In fact, Triumph had to find new vendors that were capable of manufacturing such large parts, and has equipped the new engine line with electric-motored lifts to ease assembly. Fortunately, computer modeling allowed engineers to scrutinize everything on-screen before hard parts were commissioned. That’s important when your engine cases alone cost $1 million, or about 25 percent of the bike’s total R&D costs.

In spite of the fire damage and Vaughan’s earlier concerns, the meeting broke up on an upbeat note. “We should have a running engine in three weeks,” I was told cheerfully.

This is the company’s first longitudinally mounted engine. It is also the new Triumph’s first dry-sump design, which puts the big, whirring crank in proximity to the pavement for a low center of gravity. It also affords a seat height of 29 inches, on par with the Valkyrie.

Monster torque reaction is nullified by a counter-rotating balance shaft. The five-speed transmission, which also spins

in the direction opposite to the crank, is stacked on the left side of the engine, á la the Yamaha YZF-R1. An automotivespec starter is located behind the engine. Reduction gears ensure the clutch sees only as much torque as a Daytona 1200, so the cable-actuated pull is on par with the Bonneville. The central oil pump is complemented by a scavenge pump, with ports at each end of the engine. Valve-lash adjustment is via shim-under-bucket, with 20,000-mile service intervals-10,000 for oil and filter changes.

Fuel-injection was always part of the plan. Keihin developed the 52mm dual-butterfly injectors, with Triumph doing the mapping in-house. A similar system is used on the new Daytona 600. Ten liters of airbox-six under the seat, three in the plenum chamber and one more in the transition hose-share space with the gas tank, which holds 6.6 gallons of fuel. (Fuel mileage is expected to be better than a Valkyrie’s. Range, too.) The radiator is inverted to hide the intake hoses, but hangs in the traditional spot in front of the engine, with chromed grillwork and sidecovers to jazz up its appearance.

As for the lozenge-shaped object located below the fuel rail and above the transmission on the left side of the engine, that’s the oil tank. From the beginning, the shape and overall appearance of the reservoir was a significant styling issue. The needed volume dictated basic size, but what it should or shouldn’t look like was cause for argument. This past January, when I was shown a full-size mockup, the tank was adorned with a three-pronged fork-a trident. “Looks like you’ve settled on a name,” I ventured, referring to Triumph’s ray-gun-mufflered road-bumer from 1968. Heads nodded all around.

In April, however, Triumph-owned subsidiaries and key distributors were asked to supply their top five names for the bike. Finalists included “23,” “Crusader,” “Magnum” and “Rocket III.” Not long thereafter, “Trident” gave way to “Rocket III.” And yes, Britbike buffs, the design team is well aware that the original Rocket III was a BSA.

“Rocket III fulfills all the marketing criteria,” explained one executive. “It’s a Three, it has British heritage, and it says something about the performance of the bike.” Lettering on the sidepanels aside, there’s no denying this is the most important Bloor Triumph yet. The U.S. is the target market, and the price will not be insignificant. Three years ago, participants in the styling clinic were told the bike would cost $12,799. Now, that number has ballooned to “between $15,000 and $17,000.” At that price, how many Rocket Ills does Triumph hope to sell? The answer-6000 the first year, 4000 of which will be earmarked for the U.S.-made Vaughan’s jaw drop as if it were filled with lead. “Realistically,” he confided to me later, “I think we can sell 2500 in the first year.” At presstime, final build numbers were up in the air.

But back to our wet ride on the Triumph test mule.

“The bike is tuned to run, that’s it,” I was cautioned. “It’s not properly mapped, totally unrefined. The ergonomics are correct, but the handlebar is handmade. There’s too much span on the clutch, and the engine is very raw. There’s too much engine braking and gear whine, and it’s real snatchy. On dry roads, it will spin the rear tire at 2000 rpm. After 3000 rpm, it pulls really hard. Redline is 6500 rpm.

“The brakes, suspension and steering geometry are correct. It’s stable up to 155 mph; our test rider couldn’t hold on to the handlebar beyond that.”

Clifford glanced out the window. “Geez, it’s horrible out there,” he called out. “Do you guys really want to ride motorcycles today?”

Ummm, on second thought, anyone for tea?

Actually, my time on the prototype went off without a hitch. The bike ran much better than I was led to believe it would, which is an excellent indicator of just how hard the team is trying to hit its target. And it really is fast. From my notes: “Absolutely massive power. Blows away the VTX in top-gear roll-ons. Very little engine vibration. Light-effort controls. Stable, solid. Great brakes.”

With the cosmetically complete bike shown here scheduled to be unveiled to dealers in August, Vaughan is pleased with the outcome. “I’m happy with the way it’s evolved,” he said. “It looks good, and I think the performance will be stunning.

“It’s an important bike for us and a radical departure for Triumph in terms of what it is and how big it is,” he continued. “It was a big investment. We wanted to be in the big power-cruiser business, but we didn’t think we could follow the same path as some of the others with a giant V-Twin, or even a parallel-Twin. The logical thing was to make it a Triple, and to give it as much as we could in terms of, Hey, look at me! stuff.”

Obviously, the power-cruiser landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation since the Rocket III was conceptualized, with the most significant new model being the limitedproduction Honda Rune. When it comes to Look at me!, the Rune is in a class of its own.

“The Rune is a work of art, but not everybody is going to want to plunk down the $25K that it’s going to cost,” reasoned Vaughan. “Also, I think the Rocket III will outperform the Rune. Our bike is more about the engine and straight-line performance.”

Gentlemen, start your engines. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

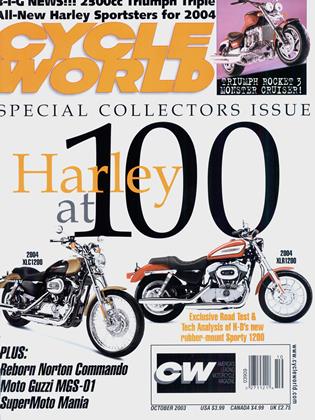

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Last Harley

October 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRevenge of the Soccer Dads

October 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClutch Players

October 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2003 -

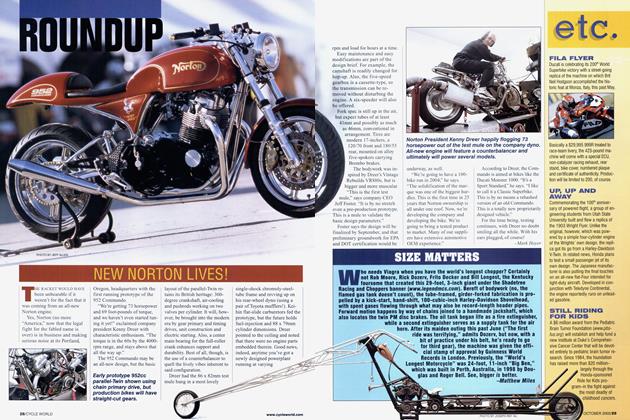

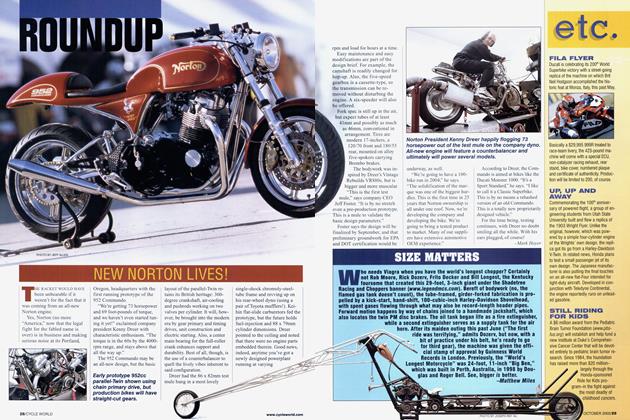

Roundup

RoundupNew Norton Lives!

October 2003 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupSize Matters

October 2003 By Matthew Miles