Two-stroke landfill

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

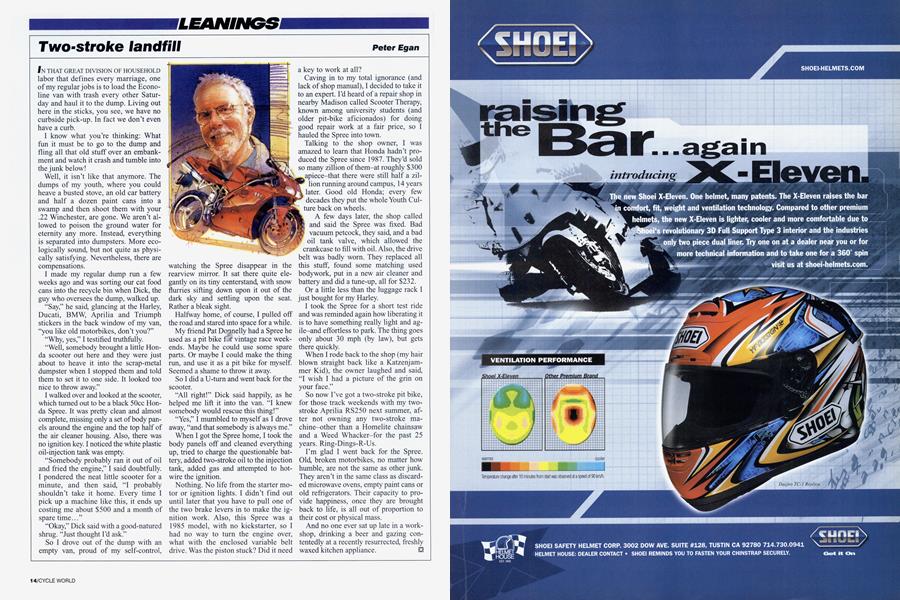

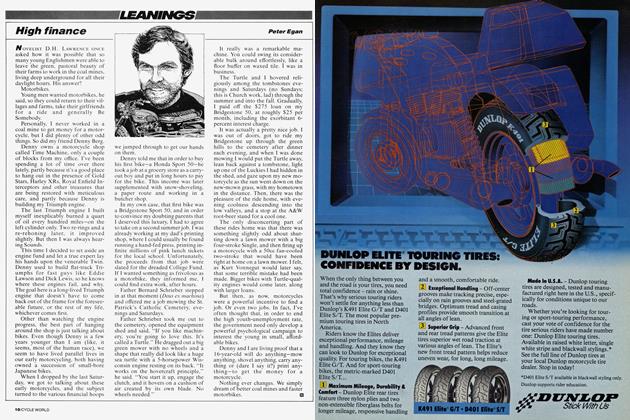

IN THAT GREAT DIVISION OF HOUSEHOLD labor that defines every marriage, one of my regular jobs is to load the Econoline van with trash every other Saturday and haul it to the dump. Living out here in the sticks, you see, we have no curbside pick-up. In fact we don’t even have a curb.

I know what you’re thinking: What fun it must be to go to the dump and fling all that old stuff over an embankment and watch it crash and tumble into the junk below!

Well, it isn’t like that anymore. The dumps of my youth, where you could heave a busted stove, an old car battery and half a dozen paint cans into a swamp and then shoot them with your .22 Winchester, are gone. We aren’t allowed to poison the ground water for eternity any more. Instead, everything is separated into dumpsters. More ecologically sound, but not quite as physically satisfying. Nevertheless, there are compensations.

I made my regular dump run a few weeks ago and was sorting our cat food cans into the recycle bin when Dick, the guy who oversees the dump, walked up.

“Say,” he said, glancing at the Harley, Ducati, BMW, Aprilia and Triumph stickers in the back window of my van, “you like old motorbikes, don’t you?”

“Why, yes,” I testified truthfully.

“Well, somebody brought a little Honda scooter out here and they were just about to heave it into the scrap-metal dumpster when I stopped them and told them to set it to one side. It looked too nice to throw away.”

I walked over and looked at the scooter, which turned out to be a black 50cc Honda Spree. It was pretty clean and almost complete, missing only a set of body panels around the engine and the top half of the air cleaner housing. Also, there was no ignition key. I noticed the white plastic oil-injection tank was empty.

“Somebody probably ran it out of oil and fried the engine,” I said doubtfully. I pondered the neat little scooter for a minute, and then said, “I probably shouldn’t take it home. Every time I pick up a machine like this, it ends up costing me about $500 and a month of spare time...”

“Okay,” Dick said with a good-natured shrug. “Just thought I’d ask.”

So I drove out of the dump with an empty van, proud of my self-control, watching the Spree disappear in the rearview mirror. It sat there quite elegantly on its tiny centerstand, with snow flurries sifting down upon it out of the dark sky and settling upon the seat. Rather a bleak sight.

Halfway home, of course, I pulled off the road and stared into space for a while.

My friend Pat Donnelly had a Spree he used as a pit bike fot vintage race weekends. Maybe he could use some spare parts. Or maybe I could make the thing run, and use it as a pit bike for myself. Seemed a shame to throw it away.

So I did a U-turn and went back for the scooter.

“All right!” Dick said happily, as he helped me lift it into the van. “I knew somebody would rescue this thing!”

“Yes,” I mumbled to myself as I drove away, “and that somebody is always me.”

When I got the Spree home, I took the body panels off and cleaned everything up, tried to charge the questionable battery, added two-stroke oil to the injection tank, added gas and attempted to hotwire the ignition.

Nothing. No life from the starter motor or ignition lights. I didn’t find out until later that you have to pull one of the two brake levers in to make the ignition work. Also, this Spree was a 1985 model, with no kickstarter, so I had no way to turn the engine over, what with the enclosed variable belt drive. Was the piston stuck? Did it need a key to work at all?

Caving in to my total ignorance (and lack of shop manual), I decided to take it to an expert. I’d heard of a repair shop in nearby Madison called Scooter Therapy, known among university students (and older pit-bike aficionados) for doing good repair work at a fair price, so I hauled the Spree into town.

Talking to the shop owner, I was amazed to learn that Honda hadn’t produced the Spree since 1987. They’d sold so many zillion of them-at roughly $300 apiece-that there were still half a zillion running around campus, 14 years later. Good old Honda; every few decades they put the whole Youth Culture back on wheels.

A few days later, the shop called and said the Spree was fixed. Bad vacuum petcock, they said, and a bad oil tank valve, which allowed the

crankcase to fill with oil. Also, the drive belt was badly worn. They replaced all this stuff, found some matching used bodywork, put in a new air cleaner and battery and did a tune-up, all for $232.

Or a little less than the luggage rack I just bought for my Harley.

I took the Spree for a short test ride and was reminded again how liberating it is to have something really light and agile-and effortless to park. The thing goes only about 30 mph (by law), but gets there quickly.

When I rode back to the shop (my hair blown straight back like a Katzenjammer Kid), the owner laughed and said, “I wish I had a picture of the grin on your face.”

So now I’ve got a two-stroke pit bike, for those track weekends with my twostroke Aprilia RS250 next summer, after not owning any two-stroke machine-other than a Homelite chainsaw and a Weed Whacker-for the past 25 years. Ring-Dings-R-Us.

I’m glad I went back for the Spree. Old, broken motorbikes, no matter how humble, are not the same as other junk. They aren’t in the same class as discarded microwave ovens, empty paint cans or old refrigerators. Their capacity to provide happiness, once they are brought back to life, is all out of proportion to their cost or physical mass.

And no one ever sat up late in a workshop, drinking a beer and gazing contentedly at a recently resurrected, freshly waxed kitchen appliance. E3