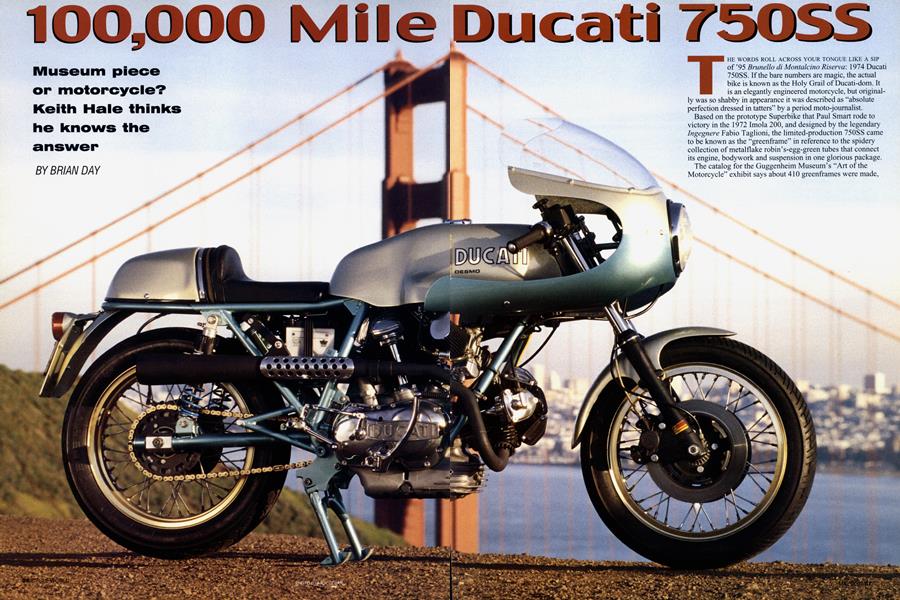

100,000 Mile Ducati 750SS

Museum piece or motorcycle? Keith Hale thinks he knows the answer

BRIAN DAY

THE WORDS ROLL ACROSS YOUR TONGUE LIKE A SIP of '95 Brunello di Montalcino Riserva: 1974 Ducati 750SS. If the bare numbers are magic, the actual bike is known as the Holy Grail of Ducati-dom. It is an elegantly engineered motorcycle, but original-

ly was so shabby in appearance it was described as “absolute perfection dressed in tatters” by a period moto-journalist.

Based on the prototype Superbike that Paul Smart rode to victory in the 1972 Imola 200, and designed by the legendary Ingegnere Fabio Taglioni, the limited-production 750SS came to be known as the “greenframe” in reference to the spidery collection of metalflake robin’s-egg-green tubes that connect its engine, bodywork and suspension in one glorious package.

The catalog for the Guggenheim Museum’s “Art of the Motorcycle” exhibit says about 410 greenframes were made, but Ducati's official figure is 200 of which perhaps 180 are still in existence, mostly entombed in private collections and museums. As a result, they're extremely valuable; a mint example with 750 original miles recently sold for $37,000 on eBay. Fortunately, greenframes are not always hidden away in vaults like rare and costly jewels. Just ask Keith Hale, a San Francisco artist who has logged more than 100,000 miles on his 1974 Ducati 750SS since buying it new. That's not a misprint: one owner, 100,000 miles on the quintessentially rough-and-randy `70s Ducati production racer.

How many times has Hale cursed the clip-ons, the tall first gear, the recalcitrant kickstarter, the skanky Bongiorno Guido Italian build quality?

Hale bought his greenframe in 1975, when he was living in Selma, a small Central California Valley agricultural town. He was 22 years old, inexperienced by his own admission, absolutely not rich and certainly not the kind of sea-

soned rider who could push the potent Ducati to its considerable limits. Searching for a bike to replace the Norton 850 Mk. II he’d “shortened” in a crash, he saw the local Ducati dealer warming-up a brand-new 750SS in front of the shop one morning. Hale was immediately hooked on the Ducati’s look and sound, and from that moment owning one became an obsession.

For the next few months in late 1974 and early ’75, he searched high and low for his dream bike with no success, then heard through the

grapevine that Jack’s Motorcycles in Fresno had one squirreled away. Disappointed to find the bike in question was really a next-generation 900SS, Hale was about to leave when he spied a glint of iridescent green paint in the back of the shop. Sure enough, Jack himself owned a prized greenframe, but wasn’t about to turn it over to some obsessive, wild-eyed kid. Jack hadn’t anticipated Keith’s determination, however, and Hale pressured him mercilessly to sell the bike. In April, 1975, after months of alternately badgering and sweettalking Jack, Hale signed the loan papers and paid $3600 for his 1974 Ducati 750SS with 17 miles on the odometer.

Hale admits the blueblooded and pedigreed Ducati intimidated him for the first few years, and he didn’t ride it very far nor very well. Learning to use the bike’s 65 horsepower and race-bred handling required that he push the limits of his own abilities.

Darrell Nealon, a childhood friend, taught Hale how to adjust the finicky desmodromic valves and perform the requisite maintenance to keep

the bike in top form. And Chris Quinn of Wheelworks, a San Leandro, California, motorcycle shop, introduced Hale to roadracing, first as a monkey on a BSA sidecar and then solo on a Ducati 250 Single. This was circa 1978, and in ’79 Hale took the 750SS to the track for the first time. He came in “second to last” in the 750cc Twins class at Sears Point Raceway. “The bike was faster than 1 was,” he admits.

Hale raced the bike in essentially stock trim, though he replaced the low Contis with high pipes to avoid the kind of crash that Cook Neilson and Phil Schilling had suffered with their famed “California Hot Rod” SS. Hale’s best finish was third in class at Laguna Seca in 1981. “The fast

guys were all at a national meet somewhere else,” he recalls, “so us slow guys got to race each other, and I made the podium.” The 750SS was campaigned at various racetracks until 1982, when its escalating value and rarity made Hale rethink the whole racing thing. “Back then you could still get parts, so I could always fix it,” he says. “But I was more and more aware of how special it was, so I decided to just ride it on the street.”

Not that he didn’t ride it often: Hale used the bike as his only means of transporta-

tion for about four years, frequently commuting from the Central Valley to the San Francisco Bay Area. And not that he didn’t ride it hard: His best time from Oakland to Selma was 2 hours and 10 minutes, the Smiths speedo often touching 130 mph along the two-lane backroads! Even so, he’s only dropped the bike once, resulting in a cracked fairing, damaged pipes and a slightly bruised ego.

“I had this route from San Leandro to Berkeley through the East Bay hills, and every time I rode it, I'd drag the Contis,” Hale recollects. “Hearing the pipes scrape got to be familiar, but one day I was leading Darrell and ran too hot into a turn...”

Hale took the 750SS on yearly treks to spectate at Laguna Seca and other California tracks. And he’s also taken it touring, to Sequoia, Yosemite, Nevada and Oregon. Yet despite the bike’s racy seating position, the owner actually finds it more comfortable than the 1995 Ducati 900SS he also owns, thanks to his compact physique.

In 1987, the Europeanspec odo quit working at 71,000 kilometers, but Hale has calculated that he’s ridden his 750SS well over 100,000 miles total.

In all that time, the bike has proven remarkably reliable, using three or four sets of piston rings (the original

rings crackea only 200U miles trom new; Hale blames brit tie factory parts installed on the Ducati assembly line), and having its vaive guides replaced several times. As the years and miles built up, however, the fabled Italian indifference to quality control began to show. "The fiberglass tank got

really rough and I had to patch the bot tom over and over again," Hale says, "Finally, it just stopped holding gas." By 1996, first and fifth gears were worn out, and shifting became sketchy. It was becoming clear that a major overhaul would soon be needed. By now, the machine had acquired a fine patina of age, hard use and loving care, and the green paint on the frame had been eaten away in places by acid from a split battery casing.

ac~ing me runas ror a compiete overnaul, 1-lale aisas sembled the 750SS in 1997 not knowing when it would be street-worthy again. But fate had a whimsical answer to his monetary dilemma. Hale is a talented and highly disciplined artist, and he conceived of a series of fine-art paintings using the Ducati's lyrically designed mechanical bits as creative inspiration. His a ti 1998 exhibition at the Bradford Smock Gallery in San Francisco was titled "Steel Life.” and ended up an unqualified success artistically and financially.

“Basically, the motorcycle paid for its own restoration,” explains Hale. “One of the ‘Steel Life’ pieces even went to an executive of the Texas Pacific Group, which currently owns Ducati!”

The artist did all the restoration work himself except, ironically, for the painting, which he farmed-out to Rand Dobleman.

The gang at Munroe Motors, a well-known San Francisco shop, also assisted Hale during the rebuild, with top mechanic Matt Prentiss generously lending his expert advice.

Hale had religiously changed his

Ducati’s straight 50-weight oil every 1000 miles, which may help explain why the complete crank assembly-something that often caused trouble in later bevel-drive engines-was found to be perfectly serviceable after 100,000 miles of hard running. He replaced the gearbox main bearings, first gear, the first-gear layshaft, the gear-selector forks and fifth gear, but resisted the temptation to make any performance modifications.

“I haven’t made any internal changes except to round-file the breakage-prone helper springs,” Hale says. “When 1 was

racing, I had visions of flowed heads, bigger valves and Imola cams, but lacked the funds to make it happen. By the time I quit racing, I had so much respect for the bike’s reliability 1 wanted to leave well enough alone.”

In his racing days, Hale had used the famous K-mart high-output coils that provided juice to the California Hot Rod’s sparkplugs, but he later switched to a Rita electronic ignition with Lucas coils for ease of maintenance. He also rewired the alternator and regulator for higher output, and replaced the leaky stock Scarab front

leaky brakes with a modern Brembo master cylinder and Grimeca calipers. The wheels were long ago upgraded, with a wider D.I.D. rear rim to accommodate racing slicks, gold anodizing on the rims themselves and stainless-steel spokes. The bike’s stock Marzocchi shocks were replaced with custommade Works Performance dampers, but the fork remains stock except for progressively wound springs. Total rebuild costs came to about $5000.

The quality of Hale’s restoration work is exemplary, with attention to detail far exceeding the Ducati’s original shoddy finish. Returned to the road in August, 2001, the 750SS has a shimmering, intense physical presence that literally stops traffic-and in one case saved the owner from an expensive speeding ticket.

“I was riding to work early one morning on a part of the East Bay Freeway known as ‘The Maze,’”

Hale recalls. “I was doing close to 120 mph. A CHP cruiser pulled me over, and I was sure I would get arrested or at least slapped with a huge fine. But the officer turned out to be a rabid motorcycle enthusiast, and we spent a good 20 minutes parked by the side of the road jawboning about old Ducatis and bikes and racing. He let me go with a warning not to do it again.”

Keith Hale’s 1974 Ducati 750SS is a tribute to the basic soundness

and engineering brilliance of Dr. T’s original design. In contrast to hearsay about the inherent fragility of bevel-drive

Ducatis, Hale has kept his Desmo running reliably year after year. Come rain or shine, he’s in the saddle and piling on

the miles. Resplendent in new paint, polished

alloy and with smartly freshened mechani-

0mm, Â - E cals, the bike looks set to carry its owner for

another 100,000 miles. I

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMad Max Found!

May 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Trip To the Barber

May 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRoom At the Top

May 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the V-Rod: Harley's Next Revolution?

May 2002 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDesmosedici!

May 2002 By Brian Catterson