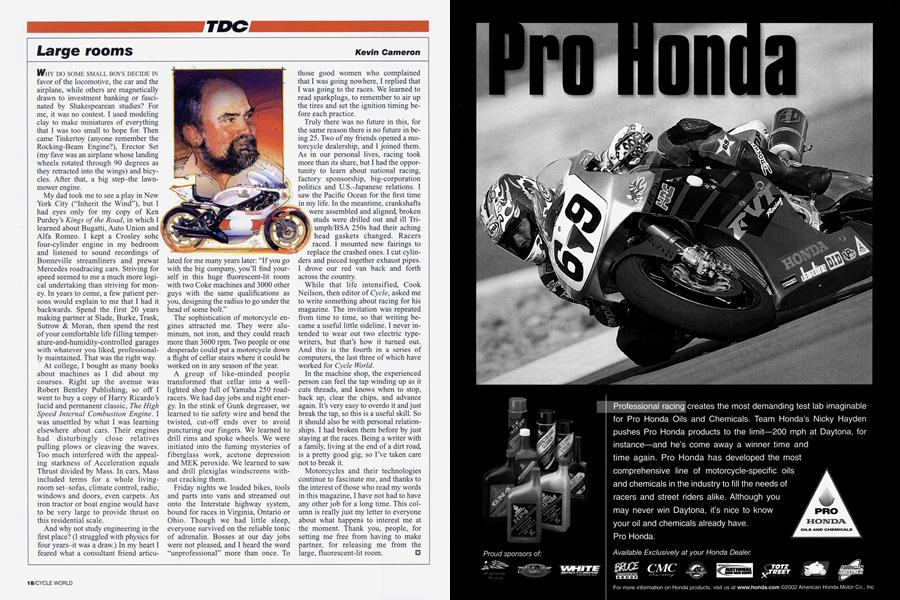

Large rooms

TDC

Kevin Cameron

WHY DO SOME SMALL BOYS DECIDE IN favor of the locomotive, the car and the airplane, while others are magnetically drawn to investment banking or fascinated by Shakespearean studies? For me, it was no contest. I used modeling clay to make miniatures of everything that I was too small to hope for. Then came Tinkertoy (anyone remember the Rocking-Beam Engine?), Erector Set (my fave was an airplane whose landing wheels rotated through 90 degrees as they retracted into the wings) and bicycles. After that, a big step-the lawnmower engine.

My dad took me to see a play in New York City (“Inherit the Wind”), but I had eyes only for my copy of Ken Purdey’s Kings of the Road, in which I learned about Bugatti, Auto Union and Alfa Romeo. I kept a Crosley sohc four-cylinder engine in my bedroom and listened to sound recordings of Bonneville streamliners and prewar Mercedes roadracing cars. Striving for speed seemed to me a much more logical undertaking than striving for money. In years to come, a few patient persons would explain to me that I had it backwards. Spend the first 20 years making partner at Slade, Burke, Trask, Sutrow & Moran, then spend the rest of your comfortable life filling temperature-and-humidity-controlled garages with whatever you liked, professionally maintained. That was the right way.

At college, I bought as many books about machines as I did about my courses. Right up the avenue was Robert Bentley Publishing, so off I went to buy a copy of Harry Ricardo’s lucid and permanent classic, The High Speed Internal Combustion Engine. I was unsettled by what I was learning elsewhere about cars. Their engines had disturbingly close relatives pulling plows or cleaving the waves. Too much interfered with the appealing starkness of Acceleration equals Thrust divided by Mass. In cars, Mass included terms for a whole livingroom set-sofas, climate control, radio, windows and doors, even carpets. An iron tractor or boat engine would have to be very large to provide thrust on this residential scale.

And why not study engineering in the first place? (I struggled with physics for four years-it was a draw.) In my heart I feared what a consultant friend articu-

lated for me many years later: “If you go with the big company, you’ll find yourself in this huge fluorescent-lit room with two Coke machines and 3000 other guys with the same qualifications as you, designing the radius to go under the head of some bolt.”

The sophistication of motorcycle engines attracted me. They were aluminum, not iron, and they could reach more than 3600 rpm. Two people or one desperado could put a motorcycle down a flight of cellar stairs where it could be worked on in any season of the year.

A group of like-minded people transformed that cellar into a welllighted shop full of Yamaha 250 roadracers. We had day jobs and night energy. In the stink of Gunk degreaser, we learned to tie safety wire and bend the twisted, cut-off ends over to avoid puncturing our fingers. We learned to drill rims and spoke wheels. We were initiated into the fuming mysteries of fiberglass work, acetone depression and MEK peroxide. We learned to saw and drill plexiglas windscreens without cracking them.

Friday nights we loaded bikes, tools and parts into vans and streamed out onto the Interstate highway system, bound for races in Virginia, Ontario or Ohio. Though we had little sleep, everyone survived on the reliable tonic of adrenalin. Bosses at our day jobs were not pleased, and I heard the word “unprofessional” more than once. To

those good women who complained that I was going nowhere, I replied that I was going to the races. We learned to read sparkplugs, to remember to air up the tires and set the ignition timing before each practice.

Truly there was no future in this, for the same reason there is no future in being 25. Two of my friends opened a motorcycle dealership, and I joined them. As in our personal lives, racing took more than its share, but I had the opportunity to learn about national racing, factory sponsorship, big-corporation politics and U.S.-Japanese relations. I saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time in my life. In the meantime, crankshafts were assembled and aligned, broken studs were drilled out and ill Tri[) umph/BSA 250s had their aching head gaskets changed. Racers raced. I mounted new fairings to replace the crashed ones. I cut cylinders and pieced together exhaust pipes. I drove our red van back and forth across the country.

While that life intensified, Cook Neilson, then editor of Cycle, asked me to write something about racing for his magazine. The invitation was repeated from time to time, so that writing became a useful little sideline. I never intended to wear out two electric typewriters, but that’s how it turned out. And this is the fourth in a series of computers, the last three of which have worked for Cycle World.

In the machine shop, the experienced person can feel the tap winding up as it cuts threads, and knows when to stop, back up, clear the chips, and advance again. It’s very easy to overdo it and just break the tap, so this is a useful skill. So it should also be with personal relationships. I had broken them before by just staying at the races. Being a writer with a family, living at the end of a dirt road, is a pretty good gig, so I’ve taken care not to break it.

Motorcycles and their technologies continue to fascinate me, and thanks to the interest of those who read my words in this magazine, I have not had to have any other job for a long time. This column is really just my letter to everyone about what happens to interest me at the moment. Thank you, people, for setting me free from having to make partner, for releasing me from the large, fluorescent-lit room.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue