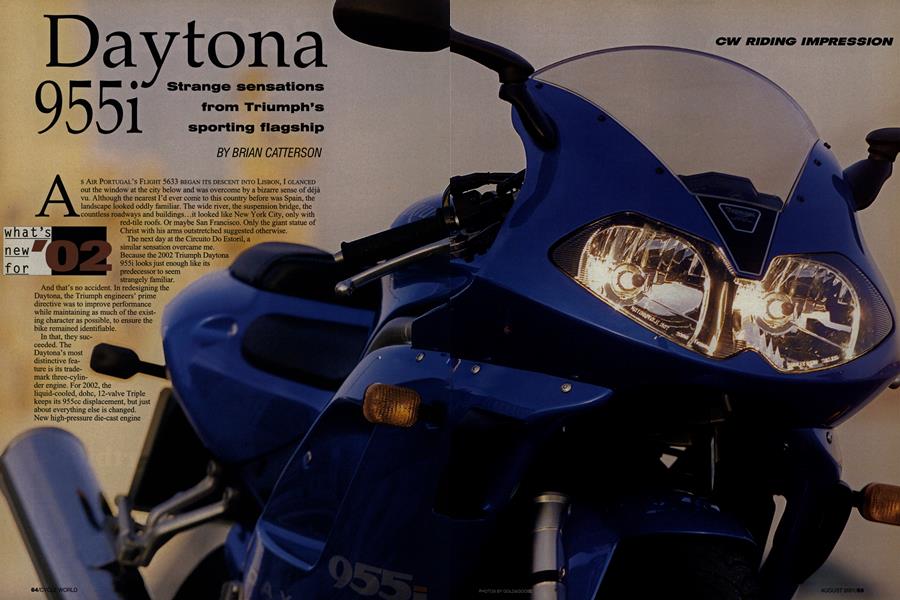

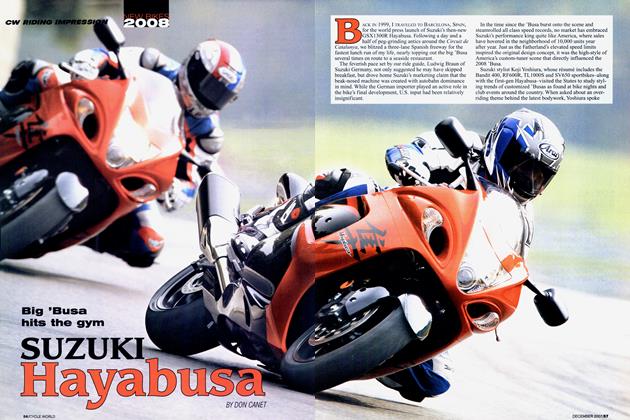

Daytona 955i

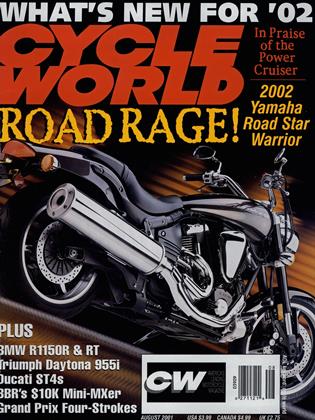

what's new for '02

Strange sensations from Triumph's sporting flagship

BRIAN CATTERSON

As AIR PORTUGAL’S FLIGHT 5633 BEGAN ITS DESCENT INTO LISBON, I GLANCED out the window at the city below and was overcome by a bizarre sense of déjà vu. Although the nearest I’d ever come to this country before was Spain, the landscape looked oddly familiar. The wide river, the suspension bridge, the countless roadways and buildings...it looked like New York City, only with red-tile roofs. Or maybe San Francisco. Only the giant statue of Christ with his arms outstretched suggested otherwise. The next day at the Circuito Do Estoril, a similar sensation overcame me. Because the 2002 Triumph Daytona 955i looks just enough like its predecessor to seem strangely familiar.

And that’s no accident. In redesigning the Daytona, the Triumph engineers’ prime directive was to improve performance while maintaining as much of the existing character as possible, to ensure the bike remained identifiable.

In that, they suc ceeded. The Daytona's most distinctive fea ture is its trade mark three-cylin der engine. For 2002, the liquid-cooled, dohc, 12-valve Triple keeps its 955cc displacement, but just about everything else is changed. New high-pressure die-cast engine cases similar to those on the TT600 have replaced the old sand-cast jobs, in the interest of more consistent production quality, less weight and reduced mechanical noise. The alternator and starter motor have been relocated to the ends of the crankshaft, eliminating the noisy gear drives employed previously. Lightweight carburized connecting rods hold forged pistons that boost compression from 11.2: 1 to 12.0:1, while smaller, lower-friction crank journals and a revised crankcase breather help raise the redline from 10,500 to 11,000 rpm.

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

Topping it all off is a new cylinder head with 1mm larger intake valves and 1mm smaller exhaust valves set at a shallow 23-degree included angle, a notable reduction from the 39 degrees of old. The intake and exhaust tracts have been redesigned for better flow, with the intakes and combustion chambers now CNC-machined to more exacting tolerances.

The Sagem closed-loop fuel-injection system also boasts a number of refinements, including smaller, lighter injectors and larger Keihin throttle bodies, which like the engine cases are now die-cast. Feeding the system is a larger under-tank airbox, with its inlets aimed backward at the rider to let him hear the intake roar. Character, you know.

The exhaust sounds better now, too, with a deeper tone emanating from the new muffler. There also are new headers and a balance pipe meant to boost midrange performance, while California models are equipped with a secondary air-injection system that reduces unbumed hydrocarbons in the interest of meeting that state’s stringent emissions standards.

Cooling has been upgraded, too, thanks to a more efficient radiator and oil cooler, plus GSX-R-like oil jets that squirt under the pistons. Revised radiator ducts route heated air away from the rider.

The net result of these changes is a claimed 147 crankshaft horsepower at 10,700 rpm, 19 bhp more than was claimed for the old Daytona. Maximum torque is said to be unchanged at 75 foot-pounds, though that figure is now obtained at 8200 rpm, 600 revs higher than before. Apply the usual 15 percent correction factor and you’re looking at a realistic 125 bhp and 65 ft.-lbs. at the rear wheel, numbers that should make the Daytona competitive with a YZF-R1, if not a GSX-R1000.

Visually, the most obvious holdover is the tubular-aluminum frame, a distinctive piece that has graced the Daytona since its 1997 debut. According to Triumph Export Sales Manager Ross Clifford, “We could have used a twin-spar frame like we did on the Sprint, and probably saved a few pounds, but we wanted the Daytona to be instantly recognizable.” That, it is. But while the frame looks the same, it has in fact been changed. The steering head now sits at a steeper, 22.8degree angle (down from 24.0 degrees), and trail has been reduced to 3.2 inches (down from 3.4 in.). There’s a new aluminum subframe, and the sexy singlesided swingarm has been replaced by a less attractive but stiffer and lighter (7 pounds, if you believe the press kit) double-sided job, painted black as if to disguise it. Wheelbase is said to have been reduced by a half-inch, to 55.8 inches. The rear suspension also was revised, with a new aluminum-bodied shock wrapped in a smaller-diameter spring (said to save 2 pounds) and a revised leverage ratio that improves action while reducing wheel travel from 5.7 to 5.1 inches. Lightening steering are a TT600-style front wheel (that saves a pound) and a 180mm wide rear tire (down from 190mm). Triumph claims these changes add up to a 22-pound weight reduction, the revised Daytona’s brochure weight given as 414 pounds dry. Swap those last two digits and you’ll probably be closer to the real number.

It seems a shame to hide most of these changes from view, but that’s just what Triumph did, cloaking the Daytona in a new fairing with a sharper nose and plastic-covered dual headlamps. Arguably less distinctive than the previous cat’seyes treatment, the new fairing certainly looks racier and more modem, which should appeal to the younger buyers Triumph is hoping to attract. Overall, the revised Daytona resembles a Kawasaki ZX-9R, particularly in our testbike’s blue (the other color is a very flattering silver).

That similarity continued beyond pit lane, because on the racetrack, the 955i evoked memories of the last ZX-9RI rode. This is both good and bad, for reasons I’ll get to in a moment.

On the positive side, the new Daytona is a runner! Holding the throttle wide-open down Estoril’s long front straightaway, the Tmmpet ripped through the gears, hitting sixth and an indicated 162 mph on the digital speedometer before braking for second-gear Tum 1. The next lap, though, it only hit 153, the difference attributable to the lack of tailwind assist. So gusty was it at Estoril that there would probably be a limerick along the lines of “The Rain in Spain,” if only there were a rhyme for Portugal.

Braking for the first comer was no problem, however, thanks to the superb four-piston Nissin brakes, and turn-in was surprisingly light-much lighter than on the last Daytona I sampled. The revised chassis and suspension also soaked up Estoril’s many bumps without deflecting.

But leaning the bike over, I encountered the bike’s first shortcoming: limited cornering clearance. Even after I’d returned to the pits and added a turn of shock-spring preload, the footpegs touched down way too easy, particularly in the long, right-hand sweeper that leads onto the pit straight. By the end

of my three 15-minute sessions, I’d ground a hole through the toe of my right Alpinestars boot, which wouldn’t have bothered me so much if this hadn’t been the first time I’d worn them! But on a positive note, the exhaust header didn’t touch down like on the old bike.

Exiting that first comer revealed another glitch: a sort of three-stage hesitation while cracking open the throttle to begin the drive down the hill toward Turn 2. Fortunately, this was only noticeable here and in the ultra-tight chicane near the end of the lap, and the old Daytona’s midrange flat spot seems to have been eradicated. Everywhere else, the engine ran fine.

No, make that fabulous, as I discovered during that afternoon’s 30-mile street ride. Triumph makes no bones about the Daytona being a stfeetbike-that’s one reason the engine displaces 955cc. too large for Superbike racing. And on publie roads, the bike was right in its element.

Our street ride consisted of tight, twisty and occasionally dirty two-lanes, punctuated by slow-moving tourist traffic-in other words, a lot like Highway 1 headed to Laguna Seca. At first I was discouraged, rowing the shift lever back and forth between first and second gear and cussing under my helmet.

But after leaving the tranny in first for one romp past a tour bus, my frown turned upside-down. With a tall first gear good for 60-plus mph and a mile-wide powerband, the Daytona is made for passing-and wheelying! After a while, I found myself leaving it in first and mono-wheeling from comer to comer, much to the amusement of my Spanish companions. (“El Americano esta loco!”) The only problem here was that the engine zinged through the rev range so quickly (yeah, that’s a problem...), I sometimes wheelied smack-dab into the rev-limiter.

On the street, I never found myself leaning over so far in a tight comer that the cracked-throttle hesitation bothered me, and cornering clearance simply wasn’t an issue. In fact, I appreciated the comfy seating position afforded by the low footpegs, narrower (though larger in capacity) fuel tank and high handlebars, which now are less pulled back than before. And despite its racy chassis geometry, the Daytona was as stable as the rocks at Capo Rocas, the westernmost point of Europe to which we rode.

So, who’d buy a Daytona? Diehard Anglophiles, obviously, including existing Daytona owners anxious to upgrade to Version 2.0. Those looking for a European alternative to a Kawasaki ZX-9R would also do well to consider it.

But there’s a whole other group that’s ripe for Daytona ownership without even knowing it. If you’re one of those sportbike enthusiasts who’s tom between an Italian Twin and a Japanese Four, stop torturing yourself and opt for the bike that strikes the perfect compromise: a British Triple! □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue