Clipboard

RACE WATCH

The Haga Saga

You’ve got to hand it to Noriyuki Haga. He doesn’t mince his words. This, for example, shortly before the 2001 roadracing season officially got under way: “Of course, 1 plan to get some wins. If possible, the world championship.” Haga was outlining his aims for his first year in the Grands Prix, riding the Red Bull Yamaha YZR500 that has taken the place of his YZF-R7 World Superbike.

“You’re very confident, for your first year,” I replied.

The stubby, tough-looking racer laughed. “No, no,” he said. “Not confident. Those are my aims, my goal. That is what you asked me.”

Haga, former wild child of the fourstroke series, was at Jerez, Spain, for the IRTA tests, along with all the other major teams-an important stage in bringing his fearsomely competitive style to the two-stroke series. He stood on the rostrum at Suzuka in 1998 as a wild card entry. But that was a one-off. Now he is a full-time GP rider, and he claims to be comfortable with switching from a production-based 750 to a feisty, full-race 500.

“When I first rode it (the GP bike), it felt very different from the Superbike,” he mused. “Everything feels more stiff, and there is no engine braking. Also, I am not used to carbon brakes.” But, bullish as ever, he made light of the task: “Already I am used to that. Anyway, I don’t use very hard braking. When you brake too hard, people overtake you!”

Haga’s switch is part of a bigger move by Yamaha, what with the manufacturer pulling out of the World Superbike series to concentrate on the GPs. Haga’s own preference would have been to stay in Superbike for one more year, but he went along with the corporate decision.

“First I was thinking to stay there until 2002, when there will be kit bikes and no factory bikes. Then I must move. But it is okay to come one year early,” he explained. You sense some regret at the loss of a possible championship-a title he might easily have won last year but for the controversial drug-test failure that cost him results and points.

“I prefer racing four-strokes, because I have spent many years on Superbikes-eight years. In ’94 I raced a 250cc two-stroke, but really I have been a four-stroke rider,” he said.

This begs another question. Is he Yamaha’s not-so-secret weapon for the forthcoming four-stroke GP future? He laughs again at the question, and answers, “If possible, I want to race the four-stroke GP bike. But it depends on this year, on my results. I have only a one-year contract!”

There is surely more to it than that, though you can’t expect a rider to reveal corporate plans that may or may not include him. Especially when Yamaha itself has been tight-lipped about its plans. But questions to the boss of racing did elicit some fuller explanations for the seemingly sudden withdrawal from World Superbike, beyond the bland “company strategy” comments of past official announcements.

According to Laurens Kleinkoerkamp, the Amsterdam-based manager of Yamaha Europe’s Motor Sport division, the decision was at least partly a protest against the uncertainty facing the future of the World Superbike series. With the GPs poised to switch to 990cc four-strokes beginning in 2002, WSB technical regulations are far from firm, and may include upping the capacity limit of multi-cylinder motors from 750cc to lOOOcc, to match the Twins.

He explained, “It came after a very long period of discussion, normal discussion about long-term and mediumterm racing strategy. We’d spoken about it for 18 months, because many things about the Superbike regulations were unclear.”

Three years previous, Yamaha (along with the other major Superbike racing factories) had signed an agreement to provide privateers with kit parts that would be the equivalent of the factory entries. During 2000, however, the FIM decided to delay introduction of these regulations from 2001 to 2002, or even withdraw them completely. It was one vagary too many.

“Yamaha and Honda wanted to go ahead as planned. It was quite late to suddenly change the regulations for the next season,” said Kleinkoerkamp. “That was one reason to stop. But there were others.”

The forthcoming new GP regulations was one, with Yamaha at that time already working on its four-stroke project. “That was also tying up a lot of resources,” he said.

But Yamaha was still developing the R7 Superbike, he continued, for the AMA series and the Suzuka EightHour. At the same time, kit parts for World Superbike privateers for 2001 are the same as for last year’s factory bike.

“We may return to Superbikes, depending on what happens in the future. The idea of lOOOcc four-cylinder bikes is interesting,” said Kleinkoerkamp.

“But the regulations will have to be fixed. There must be stability.”

As for Haga, it is not surprising that Yamaha is contemplating a four-stroke GP future for the man. Concluded Kleinkoerkamp: “We felt that switching to a two-stroke now would be the best

preparation for him. The YZR has similar acceleration to what we expect from a four-stroke GP bike-closer than a Superbike. Also, he will have a chance to learn the tracks.”

Can’t ask for much more than that.

Michael Scott

Two-stroke, tour-stroke

Yamaha’s YZ250F four-stroke made a hugely successful racing debut in the AMA 125cc Supercross Series. Costa Rican Ernesto Fonseca won four of the first five rounds in the 125cc West Region, and Nathan Ramsey finished second in the East Region opener. Is this the death knell of two-strokes in the dirt?

I remember when 300-pound Matchless and BSA Gold Star 500 Singles were wrestled around New England “scrambles” tracks, their 35-horsepower four-stroke engines seldom revving above 5000 rpm. They were built for the ages, with heavy tube-and-lug chassis and separate engine-and-gearbox powertrains, held in place by big engine plates and long bolts. Riders had to be mighty because engines were weak and bikes heavy.

Then two-strokes like Greeves and DOT invaded motocross racing. Their lightness and agility made the bigger classes seem like tractor-trailer races. Powerful four-stroke engines were more of a weight penalty than they were a power advantage. Those early two-strokes were primitive and unreliable, making maybe 20 bhp on a good day, but they were so much lighter than the four-strokes that it was no contest.

Four-strokes fought back, using extreme measures like BSA’s titanium frame, but the need to carry a heavy flywheel set in massive engine cases was ultimately too much of a handicap. The Spanish two-strokes, with much more power than engines from rainier parts of Europe, showed the way to rocketship acceleration with no loss of agility. The Japanese added endless power, suspension and reliability development.

Explosive power coupled with light weight led to a special two-stroke riding style. The smaller the engine, the more like a roadracer it was tuned, the more and closer gearbox speeds it needed, and the more precise its rider had to be to keep it in the powerband. Today, a single-cylinder 125cc twostroke roadrace engine makes 50 crankshaft horsepower at 12,500 rpm, and an MX engine is not far behind that. All two-stroke MX engines use some kind of powerband-broadening devices, such as powervalves and 3Dmapped ignitions.

With a blare of trumpets, the fourstroke off-road engine is now being revived on a whole new basis, Yamaha leading the charge with its YZ426F and YZ250F. Instead of straight displacement divisions, four-strokes in the AMA’s “250” and “125” classes are given essentially double the displacement, based on the fact that they fire half as often. Why wasn’t this done in the first place, back in the 1960s? Because while two-strokes do fire twice as often as four-strokes at equal rpm, in 1960 their pitiful cylinder-filling ability was less than half that of a good four-stroke. The result was competitive only because of its lightness. No one in those days could know that twostroke power would quadruple in three decades, so equal displacement classes seemed fair and proper.

The last of the BSA 500cc fourstrokes made 40 bhp. A modern 125cc two-stroke makes at least that much power, with 50-60 pounds less weight. No contest. Today, two-stroke cylinder filling almost equals that of fourstrokes, so given equal rpm, to get horsepower equality you need doublesize four-strokes. Even that still puts the ball in the four-stroke builder’s court to somehow attain reasonable weight.

Weight reduction is the heart of today’s off-road four-strokes, built for high rpm. Because flywheel effect increases with rpm, high-rev four-strokes don’t need the mill-wheel crankshafts of the old Gold Stars. Rolling-element bearings cut the need for oil circulation, sumps or tanks. Small cranks mean lighter cases, lighter engines equal lighter bikes.

Four-stroke power is different, too. Instead of pumping with acoustic pipe waves, the four-stroke has its separate intake and exhaust strokes for that. Pipes work only in a narrow range, but piston pumping works from low revs to high. This gives a four-stroke engine a wider powerband, so the rider shifts less often and devotes less brain-space to engine management. The four-stroke’s superior tractability also lets its rider run tighter lines than his two-stroke competition, finding traction where a two-stroke cannot.

The performance contrast between two-stroke and four-stroke makes the nature of the track very important. The four-stroke works better in heavy going and where total area under the acceleration curve counts. The twostroke gets away where sheer powerto-weight rules.

The four-stroke’s Achilles’ heel is hard starting. In fact, the only race Fonseca has lost to date was caused by his stalling the bike and struggling to re-light it. Don’t be surprised if tiny electric re-starters are soon standard equipment on MXers.

Who wins ultimately? Unless directinjection saves the two-stroke, government emissions standards will ultimately throw the contest to the four-stroke. This means another painful transition in off-road power. Just as the Matchless owners hated the little DOT 250 “ringdings” in 1962, now 125cc two-stroke riders and manufacturers are oppressed by the "unfairness" of giving "diesels" double displacement. Life isn't fair. It doesn't even have to make sense. But we do have to cope with it.

Kevin Cameron

Dave Schultz drag racer, 1948-2001

To understand what type of individual Dave Schultz was, it’s important to know what he wasn’t. Schultz, drag racing’s winningest two-wheeled racer and a sixtime NHRA Pro Stock Bike champ, who passed away on February 11 following a six-month battle with colon cancer, wasn’t the kind of vocal individual who craved the limelight or was prone to shameless displays of self-promotion.

Rather, Schultz was a dignified and stoic family man-an individual who led by example and whose actions, both on and off the racetrack, spoke much louder than his words. For more than two decades, the soft-spoken, deep-thinking Schultz ruled the quarter-mile. No one has won more drag races on a motorcycle or did more to transform the sport of motorcycle drag racing into a mainstream motorsport.

In his prime, Schultz was virtually unbeatable. With wife Meredith and engine builder and crew chief Greg Cope by his side, he won NHRA championships in 1987, ’88, ’91, ’93, ’94 and ’96. In 14 years on the NHRA tour, he never finished lower than seventh in the points standings. His dominance was never more evident than in 1993. He survived a 175-mph crash at the season-opener with little more than a broken wrist, and returned to win seven of the next nine events.

The following season, Schultz reeled off eight straight wins, an NHRA record for professional competitors that has yet to be broken, and finished with a 40-2 record in elimination rounds. In 1994, Schultz also became

the first and only rider to win Pro Stock’s triple crown when he captured the NHRA, International Drag Bike Association and AMA/Prostar Series championships in the same season. All told, Schultz’s career included 15 national championships and more than 150 major event wins. He was also the first Pro Stock Bike racer to run in the 7.5and 7.3-second zone, and the first to top 180 mph.

Schultz learned of his cancer just days before the start of the Brainerd, Minnesota, event last August, but it didn’t stop him from racing that weekend, or reaching the final round. He underwent surgery a few days later and was back at the racetrack within a week, helping to guide replacement rider John Smith to a runner-up finish at the U.S. Nationals.

Schultz’s final race will forever be remembered as a profile in courage and inspiration. Weary and weakened by a series of draining chemotherapy treatments, and 20 pounds under his normal riding weight, he mounted his 190-mph Sunoco Suzuki at the Super nationals in Houston Raceway Park and claimed the 45th and final win of his storied career. The sight of Schultz on the podium, hoisting the winner's trophy, was one of the year's most poignant images.

During his illness, Schultz never allowed his condition to dampen his competitive spirit. Days before his death, he was hard at work in the wind tunnel at Purdue University, refining the aerodynamic package of his Suzuki in preparation for the start of the NHRA Pro Stock Bike season at the Gatornationals in March. Sadly, the 2001 season will be the first one in more than two decades that will start without Schultz.

His passing is another blow to a Pro Stock Bike class that still feels the pain of the untimely death of Schultz’s friend and rival John Myers. The future of the class now rests in the hands of today’s young stars, especially Matt Hines and Angelle Seeling, who have claimed the last four season titles. Hopefully, they have taken a lesson from Schultz and Myers, and will carry on and represent the sport with the same dignity and grace that they exhibited. -Kevin McKenna

Watts up?

Shane Watts is not your typical offroad racer. Then again, the 28-year-old Australian is not your typical National Champion, either. In taking the AMA Grand National Cross Country Championship last year, he slaughtered the competition not only with his riding, but also with his laid-back attitude, odd racing strategy and unprecedented versatility on a wide range of machinery. Simply put, Watts was on a mission.

He states plainly, “I’m just a simple country boy from Australia.” Simple, maybe, but he was also raised by a father who was Australia’s first national enduro champion, so riding was in the family. Trail riding came first, and then motocross. When Watts was old enough, he won six national enduro championships Down Under, as well as a 500cc MX title.

After finishing high school and vocational training in oil-rig instrumentation, he headed off to Europe to seek more competition. “I never set out to win world championships,” recounts Watts. “I just went out to win races. I have a very competitive nature and a drive to compete.”

This drive led to the 1997 125cc World > Enduro Championship, not to mention an overall individual win at the 1998 ISDE in his homeland, also on a 125. From there, the path led Watts to the U.S. “The lifestyle in Europe wasn’t for me,” he explains. “But I’d been to America, and I knew I’d like the crosscountry format of racing for three hours. And, of course, there was better support and money.”

Once Watts got here in ’99, he won four of the first five GNCC rounds in convincing style, leaving his competition wondering where he came from. Granted, this wasn’t the first time a Eu-

ropean champ had competed in the GNCCs. Englishman Paul Edmonson has raced stateside for years, but he didn’t adapt as quickly as Watts. Things were looking good for the young Aussie, until a mid-season knee injury put an end to his title hopes. He did, however, come back to win the last two rounds after his knee healed.

In typical Watts fashion, he returned for 2000 not just ready for battle, but with what seemed like a far-fetched goal. “I wanted to win on every size bike that KTM makes,” he recalls. “It wasn’t the best plan for the championship, but it was a goal I set for myself.”

And he nearly met that goal, winning on 125, 200, 250, 300 and 380cc twostrokes, as well as on the 400cc fourstroke models. The 520cc Thumper was the only KTM Watts didn’t ride to victory, probably because it’s not the best choice for tight woods racing. Watts netted the GNCC title in the end, and left a host of crushed competitors in his wake.

A hidden side of Watts emerges with his admission that he’s a perfectionist. This comes as a bit of a surprise, especially when you look at his bikesstockers with maybe a pipe and a set of handguards added. No fancy suspension work, very few stickers, and a maintenance program consisting of little more than a hosing down and new air filter. “I don’t like to make excuses,” he says. “If I don’t win, I wasn’t the best man that day. But I have confidence. I see myself winning all year. Now that I’ve been here a bit, I’ve got experience and skill.”

If you think Watts’ stock bikes are odd, then how about the fact that he lives in his box van and sleeps at the racetracks? “That’s just who I am. I like to camp with my mates in the bush,” he says with a brisk accent, making you wonder if he ever gets homesick. His response: “I like the States, but I miss a good Aussie hamburger. You guys can’t make a hamburger. And I bring my own vegimite with me.”

Watts also brings a plan for the 2001 season, which is to continue shaking up the ranks. “I took some time off, then started training to get up to speed,” he says. His ploy obviously worked, as Watts took the win in the opening round of the first-ever World Off-Road Championship Series on his personal favorite KTM, a 200 E/XC.

The new series is touted as the West Coast equivalent of the GNCC. He says, “Being out West, it was a bit faster and there was more dust than I was used to. But I was learning every lap and getting faster.” In the process, he beat out GNCC regulars Mike Kiedrowski and Steve Hatch.

Also on Watts’ ’01 schedule are several National Hare Scrambles and, of course, defending his GNCC title. But don’t be surprised if Watts shows up at the Daytona Supercross or qualifies for an Outdoor MX National. He explains,

“I just like the kind of racing where you can get a bike from the dealer’s floor and go out and win a national on it.” At least if you’re Shane Watts, you can.

-Jimmy Lewis

Kocinski steps down, Slight steps in

John Kocinski has an impressive résúmé. He’s raced against the greats in Grand Prix and World Superbike, and has won world championships in both. And after an up-and-down season last year in the AMA Superbike series on a Vance & Hines Ducati, he was looking forward to having another go at the championship with the new Competition Accessories factory-supported Ducati team.

But that’s not going to happen. Kocinski, whose racing career spans enough years that he’s raced against Eddie Lawson, Wayne Gardner, Wayne Rainey, Kevin Schwantz, Mick Doohan, Alex Criville, Max Biaggi, Scott Russell, Carl Fogarty and Colin Edwards-world champions all-has decided to sit out the 2001 season.

“I tried to put this deal together with Competition Accessories, but from what I could see there were maybe some budget problems,” Kocinski said. “In the end, there was some ‘creativity’ in the (most recent) contract, which I thought we had worked out in December. But the December deal and the February deal didn’t match. So it was best they find someone else.”

Neither Kocinski nor Tim Pritchard, the man in charge of the Competition Accessories racing effort, would comment on the specific breaking point, although Kocinski said he felt the team didn’t appear to have what he needed to be competitive. “What I want people to understand is that I’m not asking for anything except the basic things you need to go racing,” he said. “By the basic things, I mean mechanics, suspension technicians, a computer and someone to run it, a couple of bikes and a truck to haul everything. To win a championship, I know what is necessary. You need the basic things. And the competition has the basic things plus. I’ve worked with the best teams in the world and I know what I need to win. >

“I can’t go and ride for fun,” he continued. “When I show up, everyone expects me to win. I don’t mind being under the gun and under pressure, but 1 can’t go to the racetrack and have no ammunition to fight.”

A blow to the team, if not the series, then, losing a major talent such as Kocinski? Well, maybe not. When it became clear the deal with the Californian wasn’t going to work out, Ducati North America and Pritchard tracked down newly unemployed Castrol Honda World Superbike rider Aaron Slight. A week later, the New Zealander was riding Kocinski’s vacant 996 at a Willow Springs test, and working with Kocinski’s own hand-picked mechanics, although at least one of them was considering leaving the team.

Slight, dropped from Castrol Honda after racing in the series since ’89, was immediately up to speed on a track and motorcycle he’d never seen before. His best time was 1:20.65, about 1 second off Yoshimura Suzuki’s Mat Mladin, who was also testing at the Southern California facility. “Mladin was showing him some lines and Scott Russell worked with him for a few laps, too,” Pritchard said. “But it was remarkable. He’s a tremendous talent.”

Slight hasn’t yet signed a contract with the team, however, because he’s been working on securing a part-time ride in the British Touring Car Championship. “Aaron’s put a lot of priority on that since he’s near the end of his motorcycle racing career, so right now he’s trying to focus on both,” Pritchard said.

Kocinski’s immediate future, meanwhile, is worked out. “I’m a real estate investor,” he said. “I’ll be in the Beverly Hills area this week. I’m just working on some new projects we’re trying to put together. I’ve been doing it for about a year and half.”

One of those is an $8 million estate he purchased for himself, and he’s been involved in various other transactions of similar value for profit.

“I’ve had unbelievable success,” he said. “Like anything, you just have to have good instincts about knowing if it’s the right deal or not. Then you have to go in and actually make the deal.”

Kocinski has, in recent years, negotiated all his racing and sponsorship deals himself, and commented that once you’ve dealt with entities worth billions of dollars (Honda, perhaps?), working at the level he’s at now is quite comfortable.

He hasn’t given up on racing, however. “If the conditions are right, I would stick my neck on the razor’s edge because that’s how much winning means to me,” he said. “I race because I have a passion for racing. My passion is simply winning.”

And so Kocinski says he will continue to train on his motocross bike and hone his considerable riding skills while waiting for the right deal. “I guarantee at some point somewhere in the world, somebody’s going to fall down and get hurt. You never know what opportunities will come my way. I’ll be ready. I couldn’t ask for a better life than what I have now. I’m 32, healthy and have a great career. Why take the 1S(

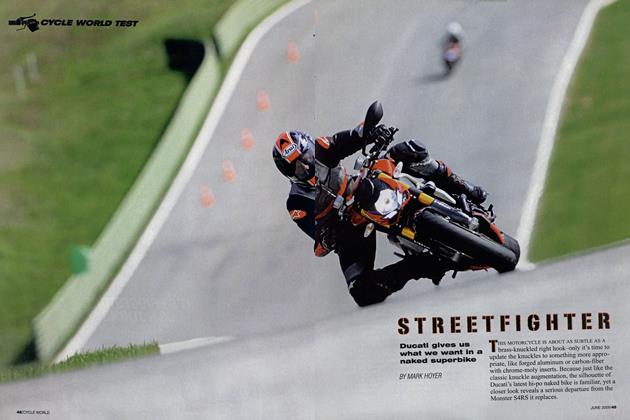

Mark Hoyer