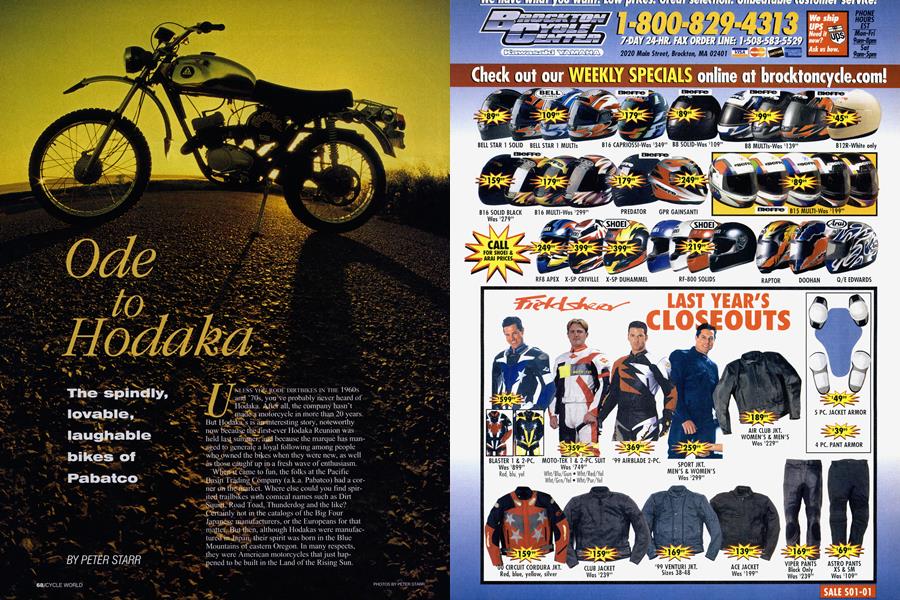

Ode to Hodaka

The spindly, lovable, laughable bikes of Pabatco

PETER STARR

UNLESS YOU DIRTBIKES IN THE 1960s and '70s, you've probably never heard of Hodaka. After all, the company hasn't made motorcycle in more than 20 years. But Hodaka's is an interesting story, noteworthy now because the first-ever Hodaka Reunion was held last summer, and because the marque has managed to generate a loyal following among people who owned the bikes when they were new, as well as those caught up in a fresh wave of enthusiasm. WEien~t came to fun, the folks at the Pacific ,Dasjn Tr4ding Company (a.k.a. Pabatco) had a cor ner o~ th~tnarket. Where else could you litid spir ited trailbikes with comical names such as Dirt Squit~, Road Toad, Thunderdog and the like? .C~rtainly not in the catalogs of the Big Four Japan~~ç manufacturers, or the Europeans for that ma~ter.~ But then, although I lodakas were manufac ture~~n~apan, their spirit was horn in the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon. In many respects, they were American motorcycles that just hap pened to be built in the Land of the Rising Sun.

Pabatco headquarters were in a small rural town called Athena (population: 1000). The company was established in 1961 as a division of Farm Chemicals of Oregon, which distributed fertilizer throughout the Pacific Northwest. To create bigger profits, company executives planned to trade local ly grown produce for whatever products friendly nations felt they could sell in the U.S. At the time, currency was regulated by stringent V exchange restric tions, and as such was in short supply. The Japanese needed American cur rency to buy wheat and other crops, and by trading goods the currency issue was sidestepped. Through this process Pabatco met Yamaguchi, and motorcycles quickly became their most signif icant business. By 1963, Pabatco had imported 5000 machines and distributed them through its 480 dealers. But in April of 1963,

Yamaguchi suddenly went bankrupt, leaving Pabatco and a well-established dealer network with nothing to sell.

This is really where the American Hodaka story begins. Yamaguchi’s bankruptcy, in addition to leaving Pabatco in the lurch, threatened to sink the Hodaka Industrial Company of Nagoya, Japan, supplier of engines to Yamaguchi. Swift, creative thinking from the nowrabid trail riders at Pabatco brought them to the only acceptable conclusion: “Let’s build our own bike!”

After all, these enthusiasts knew what American buyers wanted, the Hodaka engineers knew how to build engines and transmissions, and together they were abundantly capable of designing, producing and marketing their own motorcycle. Pabatco offered to design and market the bike if Hodaka-whose name in Japanese means “to grow higher”-would adapt its factory to manufacture and assemble the entire machine. Seeing as how it didn’t have a lot of options if it was to recoup its engineering investment and sell the 300 engines still sitting on its factory floor, Hodaka agreed.

Key in developing the initial concept of what a Hodaka trailbike should be were Henry “Hank” Koepke and Adolf Schwartz. Koepke was an employee at Pabatco who took the lead in keeping the company in the motorcycle business. And Schwartz, a retired Harley-Davidson dealer, was Koepke’s friend and mentor.

While Pabatco’s development team flailed about, day in and day out, designing and testing the “perfect” trailbike in the mountains that graced their backyard, Hodaka wasted no time in redesigning its factory. By 1964, the first Pabatco-designed Hodaka rolled off the assembly line. It was a sturdy, dependable and, for its time, high-performance trailbike that fulfilled the needs of the burgeoning market. The single-cylinder two-stroke was named the Ace 90, and in addition to many design firsts, it was street-legal, meaning it could be ridden to the trailhead rather than hauled on a truck or trailer. And its $379 price tag proved to the public that motorcycling was affordable to just about anyone.

In designing the Ace 90, the Pabatco team looked at the leading machines of the day-Cotton, Greeves, Dot, etc.-and built into their bike all those goodies on their personal wish lists. Cotton was the most influential of these brands, as the Ace 90 adopted the British bike’s double-downtube frame-a feature other trailbikes of the time did not have.

Although planned obsolescence was the order of the day in automobile manufacturing, Pabatco’s designers decided early on that instead of creating a new model each year, they would refine the basic design as dictated by engineering or customer demand, and not fall foul of fad or fashion-inspired cosmetics. Like Henry Ford’s decree from years earlier, Hodakas were available in one color only (red), to eliminate the need for multi-color parts inventories and help achieve a higher resale value. In 1965, Shell Chemical, a division of the Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company, purchased Farm Chemicals

of Oregon, Pabatco's par ent compa ny. What Shell did not under stand at the time was that it now owned a

motorcycle company!

At this time, Pabatco was little more than an extra file cabinet, and somewhere in that cabinet was Hodaka motorcycles.

But it was a favorite file cabinet of Ed Miley, one of the three original shareholders. When Shell’s principals “discovered”

Hodaka, they simply shook their corporate heads and let Miley continue to play in his personal sandbox. And why not? The motorcycle division was profitable and growing, albeit in an area that made the Shell executives nervous.

In June, 1966, the 10,000th Ace 90 was shipped from Nagoya-an amazing feat from a company that had looked extinction squarely in the eye just three years earlier. That same year, to display their faith in their product, Marketing Manager Marvin Foster and crazyman Frank Wheeler rode a couple of Ace 90s on a 3800-mile tour of Baja, Mexico, without experiencing a single mechanical failure. Marvin later settled down to corporate life in Oregon, but Mr. Crazy went on to ride a Hodaka 125 around the perimeter of Australia in 1972, covering 10,000 miles in 21 days.

You know what happens when two trail riders get together for a Sunday ride? Yes, the spirits get lifted and a little contest ensues. Last guy to the river is a Nancy! Well, that’s probably how the first racing Hodaka was conceived, and in short order the little trailbikes were winning all manner of races. Famous names such as Jim Pomeroy, a native of nearby Yakima, Washington, and the first American to win a Motocross Grand

Prix (Portugal, 1973), and Sammy Miller, the world trials champion, rode Hodakas in competition. And the diminutive Harry Taylor even rode a Hodaka to victory in the 1968 Daytona lOOcc roadrace. Whether it was motocross, desert, observed trials, flat-track or roadracing, Hodakas made an indelible mark on the competitive map of the day.

Such was the level of success that by the fall of 1969, Hodaka was ready to begin limited production of a straight-out-of-the-crate racer for under $500. The boys from Athena scored another marketing coup, and by January,

1970, the first shipment of Super Rats arrived in the U.S. The bikes were winners straight away, and the magazine testers of the day welcomed them with open arms.

Never ones to rest on their laurels, Hodaka in 1972 heeded the calls from its customers and

customers designed an entirely new motorcycle, powered by a 125cc engine, called the Wombat. This was later joined by Hodaka’s second purpose-built racer, the Combat Wombat, which was a much more serious machine than the Super Rat.

During the spring of 1973, northeast Oregon hosted the Bad Rock Two-Day Qualifier. World-class competitors such as Malcolm Smith rode more than 450 miles across the snow-covered Blue Mountains in their quest to eam a place on the U.S. International Six-Day Trials (ISDT) team. Marvin and his peers at Hodaka saw the event as a marketing opportunity, and commissioned the production of a film for television distribution-the first of its kind. “The Bad Rock” was seen on TV stations across 70 percent of the country, and became the next marketing plateau onto which Hodaka leaped and others feared to tread.

While it could be argued that Hodaka created the trailbike market, no one would dispute the fact that the company introduced a tremendous number of people to the sport on a first-class bike that didn't cost a fortune. Yet the company's marketing efforts never lost sight of the reason people ride motorcycles: They're fun!

So, what brought about the demise of this cheerful ftíZÍV/w little company? As might be expected, there was not Just one reason, but many. Principle in the years prior to 1979 might have been the comI ^^B pany’s inability to adopt the latest technology at a pace to match its now much bigger rivals. What Hodaka got was whatever obsolete components were leftover after the bigger companies (namely Honda and Yamaha) had chosen theirs. Another factor was the sheer size of Hodaka’s competitors, who were able to subsidize their dirtbike sales with profits made from their streetbikes.

The short version of what led to the end was the economic recession of the late ’70s. The dollar was devalued against the yen, making Japanese products too expensive for the American market. There was a glut of competitors’ bikes in the U.S. that were being sold at fire-sale prices, and Shell began to view its struggling motorcycle division as a liability rather than an asset. Hodaka either had to get bigger with better or more complete control, or be disbanded. In vying for the former, Shell tried to purchase the Hodaka engine plant, but the Japanese wouldn’t sell, so Shell decided not to renew the manufacturing contract and the business was shut down. Hodaka later sold its tooling to a Korean company that used it to make utilitarian motorcycles for the Asian market.

So, why did 600 enthusiasts descend upon Athena in June, 2000, to honor this long-dead marque? Mostly it was due to the single-minded enthusiasm of Paul Stannard, who has become the force majeure of the Hodaka revival. This Rhode Island resident owns 200 (!) Hodakas, and has sourced the manufacture of spare parts to the original specs (www.strictlyhodaka.com) for people who, like him, enjoy buying and restoring Hodakas. This gathering brought out the obscure and the famous alike, with such luminaries as Jim Pomeroy taking a leading role in making sure everyone had a riotously good time. Can you spell f-u-n yet?

Many of the original employees that helped create Hodaka were there, too, including Marvin Foster, Harry Taylor, Jim Gentry and Chuck Swanson. Everyone agreed that the spirit of Henry Koepke, killed in a street accident in 1967, wove itself with vibrant color through the tapestry of this event. The Grand Marshall was Mildred Miley, the charming and erudite 85-year-old widow of the former head of Pabatco, who wore a sash emblazoned with “Mrs. Hodaka.”

The two-day event began with a parade though the town of Athena, passing the original “factory” en route to the local baseball field. There was the obligatory concours d’elegance, with the original Hodaka luminaries serving as judges, a swap meet and a field trials, which included a weenie-eating contest wherein riders attempted to eat hot dogs dipped in jabanero-laced (read: stupendously hot) mustard off of strings! For those who didn’t have a job to go to on Monday, there was a trail ride that retraced part of the Bad Rock trail.

The weekend-and perhaps the very essence of Hodaka-was best summed up by two of the key people dedicated to keeping the brand alive. First Foster: “I was attracted to Hodaka by an ad I saw in Cycle World, with a photo of the Ace 90. The bike was a significant departure from the other trailbikes that were step-through, pressed-frame models with the engines hanging down below. When I found out that it was designed by a few dedicated off-road riders here in Oregon, I had to join them. It was great-a handful of trail riders with our own motorcycle factory. I’d have worked there for free!”

And second, Stannard: “Hodaka is more than just a motorcycle brand. The Hodaka name represents the bragging rights and vivid memories of all those who have ridden them. My friends and I are excited to be able to keep them alive. If you ask a Hodaka enthusiast to sum up Hodaka in one word, you will always hear the word ‘fun.’ ”

Yes, had these people not known the true meaning of the word fun, the Hodaka trailbike and the tremendous impact it had on the motorcycle world would never have happened. That alone was worthy of a reunion in 2000, and hopefully for many years to come. □

Peter Starr is a filmmaker best known for producing the motorcycle flick Take it to the Limit. When he ’s not astride one of his innovative camera bikes, he enjoys fettling his 1973 Hodaka Ace 100 B+.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

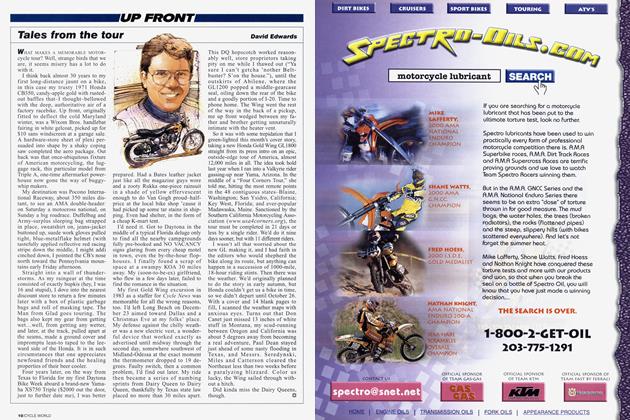

Up FrontTales From the Tour

February 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Town Too Far

February 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGordon Jennings

February 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2001 -

Roundup

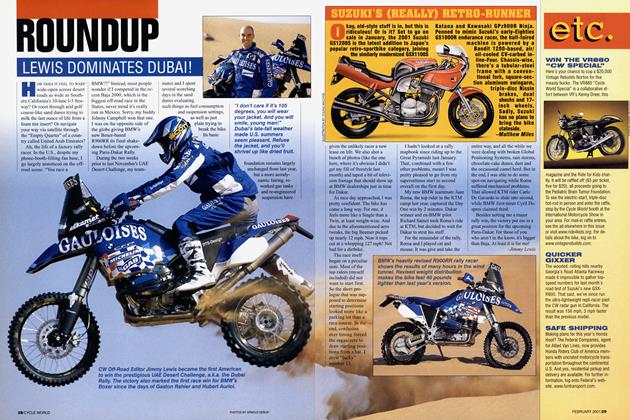

RoundupLewis Dominates Dubai!

February 2001 By Jimmy Lewis -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's (really) Retro-Runner

February 2001 By Matthew Miles