A town too far

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

WHEN I RODE INTO TOWN ABOUT TWO hours before sunset, it occurred to me that Jackson, Wyoming, had everything a touring rider could want at the end of a long, hot day.

Motels, movie theaters, Mexican restaurants, invitingly cool bars with invitingly cool drinks, camping and fishing stores to browse in, bookshops full of books on Western history and a large number of mixed tourists to gaze upon while eating an ice cream cone on a park bench. The place was jumping.

Not that I’m normally drawn to places with hoards of tourists, but it is nice to be able to walk around town at night and get some exercise without being followed by the police car because you’re the only guy who isn’t home.

I cruised the entire length of Jackson to scope out the motels, riding all the way to the western city limits and noting that several inns still had VACANCY signs burning. I pulled into a parking space and looked at my watch. It was only about 6:30 p.m.-a little too early to stop-but I had been riding my old R100RS Beemer for about 10 hours and was feeling a little buzzed.

The best way to gauge your touringfatigue level, I’ve found, is to get off your bike for a minute and shut it off. If your head is humming like a tuning fork and you can’t put change in a parking meter, it’s probably time to stop. Dropped gloves are a bad sign, too. The brain is switching over to its menu-contemplation mode (appetizer and beer list phase) and doesn’t want to be bothered with basic motor skills.

I should have turned around right then and gone back into town. But I didn’t. After all, there were nearly two hours of good riding light left. I looked at my watch and uttered those terrible words, “One more town.”

Seemed like a good decision at the time. The ride out of Jackson was stunning. I swung up through the southern end of the Teton range on Highway 22 toward Teton Pass (8429 ft.), a curving mountain two-lane with only moderate traffic. Pulling off at a scenic overlook, I flipped up my faceshield and looked at the map on my tankbag for a minute.

Hmmm. Not many big towns out there. If the motels were full in the tiny villages of Wilson or Victor or Swan Valley, my next sure bet for a hot meal and a bed would be Idaho Falls. About 85 miles away. The cars were àlready turning their headlights on, and in the dark shadows of the mountains my faceshield was beginning to shimmer with the halos of many departed bugs. Road signs warned of deer and elk. Maybe I should go back.

Yeah, that was the ticket. Mexican dinner, movie, walk. Buy a book. Have a margarita nightcap. Stop a little early for once and live like a human instead of a forward-progress machine. I turned around and rode back to Jackson, now more glittering than ever in the warm dusk.

Trouble was, much of the glitter came from newly lighted neon that said NO in front of the former VACANCY signs.

I cruised all the way back to the other end of town before I saw one lone vacancy sign, in front of a nice log-cabin-style lodge. But when I walked into the lobby I heard the desk clerk say to a family of four, “Sorry, we just gave away our last room. And absolutely everything in town is full. I’ve been calling around for the past half-hour, and there’s nothing.”

The family looked hollow-eyed and tired. So did I, one would suppose.

I had ridden right through town during that critical window of time another motorcycle journalist long ago (I can’t remember who) referred to as “the witching hour.” It’s that fleeting period every evening when motels suddenly fill up, restaurants begin to run out of their prime rib special and movies start. If you don’t stop then, you will probably be out of luck. An hour later, you’ve missed the boat. One more town is a town too far.

I have ridden through the witching hour and aced myself out of a perfectly idyllic stopping place so many times I hesitate to admit it. I generally ride through some scenic little town that’s so perfect Walt Disney might have designed it, and end up sleeping at some bleak motel out on the highway with a diesel idling outside my window, and dining on the last piece of fried chicken from a convenience store where they are just mopping up and their last customer looks like he’s waiting for me to leave so he can rob the place.

I should make a little sign and put it on the inside of my fairing that reads, “On the other side of Paradise is a great abyss.”

It was almost dark when I headed for Idaho Falls, and I made it a few hours later.

Luckily, Idaho Falls is anything but a great abyss. It’s a lovely little city right on the Snake River, with a nice park right around a real set of waterfalls (hence the name, I suppose). Unfortunately, all the motels were full.

Well, not quite. A helpful clerk at a big chain motel called all over town and found one room left, a cancellation at a remarkably inexpensive place across the river. “You’d better head over there right now,” he said. “This is, literally, the last room in town.”

“Tell them to hold it for me,” I said, slamming on my helmet without bothering to fasten the chin strap. It was starting to rain when I found the motel.

Seldom have I been so glad to see a flat bed, a roof and four walls.

I ate that night at a nearby restaurant that was just closing but let me in anyway, then had a beer at a brew pub that was also just closing but let me in anyway.

Perfect timing, once again. Another big victory for intrepidness and the Western concept of linear progress.

And nothing so warms the heart of the weary, wayward traveler as the sight of chairs stacked upside-down on tables, the quiet clack of salt shakers being refilled by a tired waitress, the reassuring sound of the night manager locking doors from the inside and the shriek of a vacuum cleaner picking up bread crumbs left by customers who dined much, much earlier.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTales From the Tour

February 2001 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCGordon Jennings

February 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

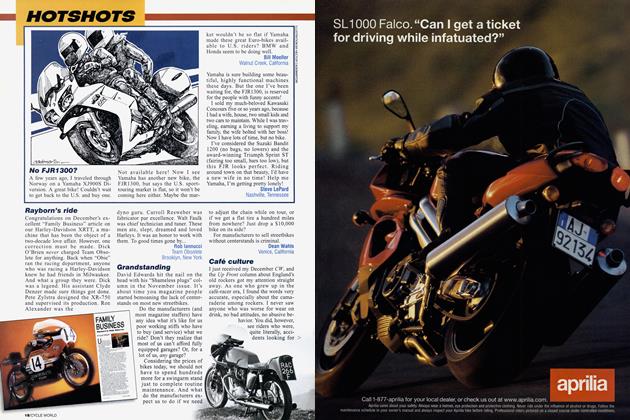

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2001 -

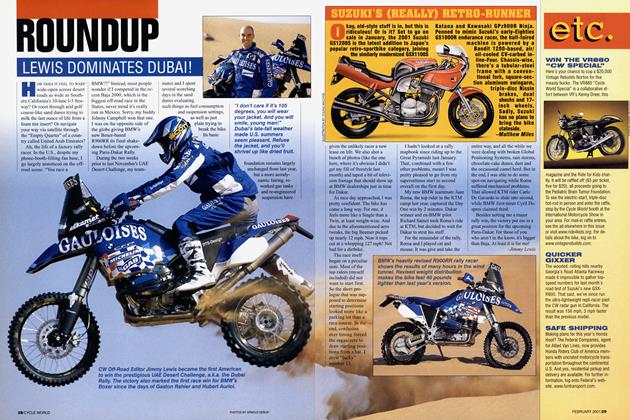

Roundup

RoundupLewis Dominates Dubai!

February 2001 By Jimmy Lewis -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's (really) Retro-Runner

February 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

February 2001