Anyone can do it

TDC

Kevin Cameron

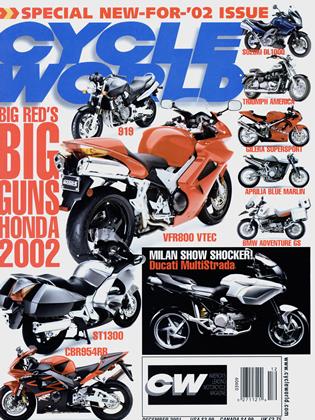

MOTORCYCLES CAN NOW BE MADE anywhere in the world where there is capital, labor and demand. This means it is no longer necessary to have a national tradition of established brands in order to enter the market.

The first example was England. Once the remnants of its formerly great motorcycle industry had self-combusted to ash, England was ripe for a new beginning. John Bloor provided it, and the new Triumph has taken its place as an established brand.

India, China, Indonesia and Thailand are more recent proofs. These industries began with “knock-down” factoriesobsolete Japanese production lines exported wholesale to other countries and operated there to produce low-priced “transportation specials.” Local industries have developed from such beginnings, so that China is now the world’s largest producer of motorcycles, followed by India and only then Japan.

These beginning industries had to be satisfied for years with reproducing outdated Japanese models, but many things worked against a continuation of that policy. National governments are quite aware of what will happen to their cities if vehicle emissions are not regulated, and this requires new technology. Local businessmen in these countries naturally ask why Japan should take a profit from their sales, so local producers seek independence. And finally, pure transportation motorcycles lead to hotter rides as these countries develop their own middle classes. This is why we saw Chinese machines up to 350cc at last year’s Munich motorcycle show.

Right now a crisis is developing between Japan and China over the issue of design piracy. Chinese copies of Japanese models are being produced without payment of license fees, with names that sound much like Japanese originals but with consonants changed here and there (“Suzaki,” for example). In the course of the past couple of years, Japanese bike sales to China have dropped substantially as Chinese factories have expanded. Japanese planners know that even if the piracy issue is somehow resolved in their favor, Chinese companies are now ready to move on from copying to original design.

This has been the pattern in all industrial revolutions. First comes a period of copying foreign examples, resulting in not only manufacturing competence but a growing understanding of design. Then comes original creation. What is more ominous for Japan is that each new country to make the leap into major industry does so with an advantage over the previous.

Germany was able, in the period 18401900, to create major industries overnight because they had the pioneering example of England’s mistakes and triumphs to guide them. Japan’s industrial base was mostly destroyed by the end of WWII, and so started afresh-with the very latest and most productive machinery and research equipment. The result was Japan’s phenomenal postwar commercial success. By contrast, England, in debt and saddled with obsolete prewar machinery and practices, endured decades of postwar stagnation.

A major business magazine recently asked the question, “Knowing that China can do it cheaper, why would you want to manufacture any of the goods they now produce anywhere else?” Chinese business is making hay while Japan struggles with its troubled banking system.

One result of this is the recent announcement of a commercial alliance between Suzuki and Kawasaki. Despite record dollar exports to the U.S., Japan’s motorcycle giants face a very contracted domestic market, now only 25 percent of what it was a decade ago. The loss of Chinese sales is a further blow that suggests sagging exports will continue as other Asian countries develop their own industries.

European motorcycle producers are well aware of these developments and are making hay of their own as fast as ever they can. Expect ever more tasty offerings from both established and new Euro producers as they rush to seize opportunities Japan cannot at the moment afford.

A major product of the European industry is refreshing variety in style. Automated manufacturing puts high quality at the disposal of all producers today. Because of this, the decision to buy is more often influenced by fashion and other emotional issues. “How will this product make me feel or look?” is the new question. Faced with a choice between a stylish high-quality Italian scooter and an equally high-quality Japanese import of dated style, which does the Italian teenager choose? Japanese industry still holds by the principles that made it great-product quality and price-but now that industrial techniques are understood worldwide, Japan has lost its monopoly in those areas.

I grew up rooting for rationally designed Japanese products in racing. I felt that a desirable and inevitable kind of revolution was taking place when in the 1960s and ’70s, lightweight two-stroke Japanese machines won races against outdated traditional designs. When Japanese production became all four-stroke, sport machines were rationalized and refined to an amazing extent, bringing to the consumer features once limited to use in only the most expensive and specialized factory racing machines. Even the former arts of handling-once held to be the exclusive province of god-like English and Italian wizards-were gradually transformed into a product by Japanese thoroughness. Beginning with the Kawasaki GPz550 and Honda Interceptor, and continuing through years of sportbike refinement, it has become possible to combine racebike-like handling, braking and acceleration with almost any desired kind of external style. Touring bikes have gained agility, cruisers have real power to back up their rumble.

The result of all this Japanese achievement is that this knowledge is now everywhere. That has created capable competitors around the world.

No one can say what lies ahead, but I expect to see strong competition and therefore a continuing powerful challenge to Japanese makers as alternatives spring into being in Asia, Europe and, yes, maybe even the U.S.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWind Machine

December 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCanadian Ducks

December 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupMerger Mayhem In Japan

December 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupIs Saddleback Back?

December 2001 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupYzr-M1 Gets Naked!

December 2001 By Matthew Miles