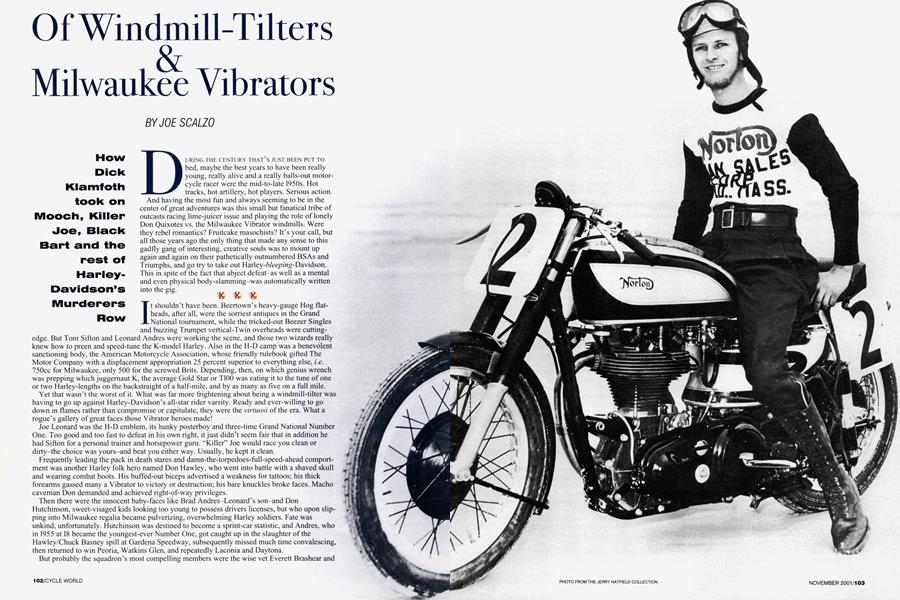

Of Windmill-Tilters & Milwaukee Vibrators

JOE SCALZO

HOW Dick Klamfoth took on Mooch, Killer Joe, Black Bart and the rest of HarleyDavidson’s Murderers Row

DURING THE CENTURY THAT’S JUST BEEN PUT TO bed, maybe the best years to have been really young, really alive and a really balls-out motorcycle racer were the mid-to-late 1950s. Hot tracks, hot artillery, hot players. Serious action. And having the most fun and always seeming to be in the center of great adventures was this small but fanatical tribe of outcasts racing lime-juicer issue and playing the role of lonely Don Quixotes vs. the Milwaukee Vibrator windmills. Were they rebel romantics? Fruitcake masochists? It’s your call, but all those years ago the only thing that made any sense to this gadfly gang of interesting, creative souls was to mount up again and again on their pathetically outnumbered BSAs and Triumphs, and go try to take out Harley-bleeping-Davidson. This in spite of the fact that abject defeat-as well as a mental and even physical body-slamming-was automatically written into the gig.

Ii t heads, shouldn’t after have all, were been. the Beertown’s sorriest antiques heavy-gauge in the Grand Hog flat.National tournament, while the tricked-out Beezer Singles and buzzing Trumpet vertical-Twin overheads were cutting-

edge. But Tom Sifton and Leonard Andres were working the scene, and those two wizards really knew how to preen and speed-tune the K-model Harley. Also in the H-D camp was a benevolent sanctioning body, the American Motorcycle Association, whose friendly rulebook gifted The Motor Company with a displacement appropriation 25 percent superior to everything else, i.e. 750cc for Milwaukee, only 500 for the screwed Brits. Depending, then, on which genius wrench was prepping which juggernaut K, the average Gold Star or T100 was eating it to the tune of one or two Harley-lengths on the backstraight of a half-mile, and by as many as five on a full mile. Yet that wasn’t the worst of it. What was far more frightening about being a windmill-tilter was having to go up against Harley-Davidson’s all-star rider varsity. Ready and ever-willing to go down in flames rather than compromise or capitulate, they were the virtuosi of the era. What a rogue’s gallery of great faces those Vibrator heroes made!

Joe Leonard was the H-D emblem, its hunky posterboy and three-time Grand National Number One. Too good and too fast to defeat in his own right, it just didn’t seem fair that in addition he had Sifton for a personal trainer and horsepower guru. “Killer” Joe would race you clean or dirty-the choice was yours-and beat you either way. Usually, he kept it clean.

Frequently leading the pack in death stares and damn-the-torpedoes-full-speed-ahead comportment was another Harley folk hero named Don Hawley, who went into battle with a shaved skull and wearing combat boots. His buffed-out biceps advertised a weakness for tattoos; his thick forearms gassed many a Vibrator to victory or destruction; his bare knuckles broke faces. Macho caveman Don demanded and achieved right-of-way privileges.

Then there were the innocent baby-faces like Brad Andres-Leonard’s son-and Don Hutchinson, sweet-visaged kids looking too young to possess drivers licenses, but who upon slipping into Milwaukee regalia became pulverizing, overwhelming Harley soldiers. Fate was unkind, unfortunately. Hutchinson was destined to become a sprint-car statistic, and Andres, who in 1955 at 18 became the youngest-ever Number One, got caught up in the slaughter of the Hawley/Chuck Basney spill at Gardena Speedway, subsequently missed much time convalescing, then returned to win Peoria, Watkins Glen, and repeatedly Laconia and Daytona.

But probably the squadron’s most compelling members were the wise vet Everett Brashear and the young, uncanny Carroll Resweber, both of whom had mysterious gleams in their eyes implying that they knew more about the craft and magic of brakeless flat-tracking than anyone else. Who could doubt it? Brashear lost an orb to the ravages of racing and came back faster and more mystic than before. Resweber’s exotic array of gifts included the dangerous pronate-the-front-wheel cornering technique, the gain-200-feet-on-the-whole-field-on-theopening-lap maneuver, and more. Unearthly powers were at work with “Mooch.”

Has anybody been left out? Only a potpourri of dozens, including such fine fellows as the ever-dependable oil-field roughneck Jack Ghoulsen, the aptly named wild roadracer Harry Fearey and the amazing Paul Goldsmith. Formerly of the Indian “Wrecking Crew,” Goldsmith, like Killer Joe Leonard, was destined to later become a car-racing star as well as a big aviation hero.

M eanwhile, in stark contrast to the murderers’ row of hard Harley faces was the laid-back countenance of the windtilters’ best boy, Dick Klamfoth. Actually, there were three Klamfoths, all radically different, and not one the face of a motorcycle racer. The first Klamfoth (circa 1946-47) was the golden blonde with the beatific smile who appeared to have stepped off a California surfer beach-exccpt no such sun-blasted landscapes were to be found in wet, landlocked hinterland Ohio where Dick did his early schooling in forest and swamp enduros. The second Klamfoth (1949-54), the maestro of the Daytona 200, was the curiosity who looked as up-to-the-minute and monumentally cool as the beatniks and bop musicians of the counterculture. In square-as-a-bear motorcycle racing, Dick was the only cat hip enough to grow a goatee, and took to wearing a stylized K with lightning bolt on his race jerseys. The third, and to H-D the most dangerous Klamfoth (1955-60) was the benign bombhead looking older than his years who had the Vibrator herd worried sick, and who was even playing and winning mind games with the great Mooch Resweber.

Klamfoth’s racing style was classic, and it never changed. Whether dirt or road, he made it look so easy. Vibrator bravos flew into combat in crouching postures of hyper-aggression; Dick hung out his skid shoe for business then casually circled a mile or half-mile in a graceful manner that seemed to say, “All is well.” Someone once suggested that his face was split into a dreamy smile of pure pleasure.

Well, perhaps. But during his big Daytona-winning seasons when he was annually spending 200 miles hanging draft in the middle of that endless tomado of raging engines and blinding coral sand and pounding surf that was “The Beach,” it’s hard imagining that the man had much opportunity to flash his pearly whites. Old Daytona was a monster oval 4 miles long, and gassing your brains out in zero visibility was crucial to its mystique. Getting off the beachfront and into the Daytona comers might have spelled relief, except that with packs of 120 starters pummeling the loose sand, the comers turned into canyons. No help there.

So when you rounded the comer and turned onto “Jungle Road,” Daytona’s notorious paved backstraight, it was smooth sailing at last? Yeah, right. A narrow and violent corridor of undulating macadam piercing wild forests of palmetto and mangroves, Jungle was a 2-milelong grapple that lap after lap dialed you straight into the middle of a battling wolfpack of hurtling leaders and slow-moving stragglers.

On account of these and other pleasantries, Daytona wasn’t so much a racetrack as a dirty trick. And it belonged to Klamfoth. He was the first post-World War II name to get a handle on the wonderful/sadistic 200 miles and became the Beach’s first three-time champion (1949, 1951,1952). Norton 88 and Manx models, plus BSA Shooting Star Twins and Gold Star Thumpers, were his cannons of choice.

And where, you might well ask, was the Milwaukee monolith during all this unseemingly Brit win-taking of Dick’s? For once, suckin’ wind. But not for long.

Sx ymbolic of the mess H-D found itself in at mid-century was this gleeful February, 1950, write-up from an anti-Harley comic: “The Harley lads never worked so hard for as little as they did at this year’s Daytona. It was hard to believe the accomplished masters of American dirt-track racing could fall so often. Lacking the speed for the straights, they had to try and make time in the comers with the resultant spills making the worst traffic jams ever seen on the north turn.” Jeering salt in the wounds, the comic tittered, “Apparently the mies will bear changing or the design of the Milwaukee product will be radically altered if the small English overheads continue cleaning up.”

That same December the Vibrator colors were literally at half-mast in memory of the demise of the last living member of the patronymic, Walter Davidson, wiped out (along with four others) in a horseless carriage while making a left turn against traffic. Contributing to the gathering gloom-besides taking a reaming from the Brits on the racetracks-Harley now also seemed to be starting to lose the sales race.

Belatedly but decisively, Milwaukee struck back. Seeking relief and protection, it hired sharks to drag the Brits into federal court so that Norton, BSA, Triumph, etcetera might experience the wrath of the U.S. Tariff Commission. And in 1953 its new Model K hit Class C racing.

The same comic made the mistake of tittering all over again: “This? This is Harley’s answer to overhead valves and vertical-Twins? This is from the company of pentroof heads and pocket valves and eight valves? This is the best U.S. brains can do?”

Within two seasons, though, the mighty Ks had performed a characteristic Vibrator bounceback and were steamrolling Daytona and all the Grand Nationals. A moaning editorial in the comic titled “Where Do We Go From Here?” predicted the total collapse of U.S.

racing unless the competition rules were completely overhauled by the AMA and the sadsack loser Britbikes caught some kind of performance break.

Fat chance. The outfit wasn’t named the American Motorcycle Association for nothing. Milwaukee didn't “own” the AMA per se, just dominated all the important committees.

So, if you were a Harlcyphoid like Dick Klamfoth, there were two unsatisfactory ways to go: crybaby or windmill-tilter. Crybabies petitioned the AMA with statistics galore proving that BSA and Triumph deserved more cc’s or at least a jump of a point or two in compression ratio. But after stating their case brilliantly, crybabies got told-sympathctically yet firmly-that they were rockheads who just didn’t understand what was going on. Actually, AMA engine rules were stacked against poor Harley, see, and in favor of the Brits! The problem was that the Brits had lousy tuners and slow riders!

Going the windmill-tilter route, as Dick chose, was going to lead to defeat, too. But abandoning the lopsided fight and jumping on an H-D was just too easy a cop-out.

T% he one Grand National season when the windmill-tilters looked like they might do something crazy and truly kick butt on the Vibrators was 1954. At Daytona, Bobby Hill’s Shooting Star came in first, with Dick’s duplicate just behind. And then out in California at the new Willow Springs road course, Kenny Eggers, a Vibrator turncoat on another BSA. bopped the Hogs again. Dick got in the act next by hammering Joe Leonard and Tom Sifton at the Richmond Half-Mile, ordinarily an H-D stronghold. When Paul Goldsmith, Leonard and Harry Fearey fiercely responded with an unbroken string of five Milwaukee scores, the windmill-tilters looked routed. But not quite. A Pacific Northwest icon, Gene Thiessen, accomplished something at Portland, Oregon, that any windmill-tilter might have traded a whole career for. The great Gene smoked off all the Vibrators on a mile track! It never happened again in six years, and accounts of what really occurred are confused. Apparently, Leonard and Sifton were tearing up the joint as ever, but some BSA eagle-eye divined that their K’s exhaust stacks were too long. All the windmill-tilters succeeded in raising enough stink to force the stacks’ removal, slowing down Killer Joe just enough for Thiessen’s Shooting Star to win.

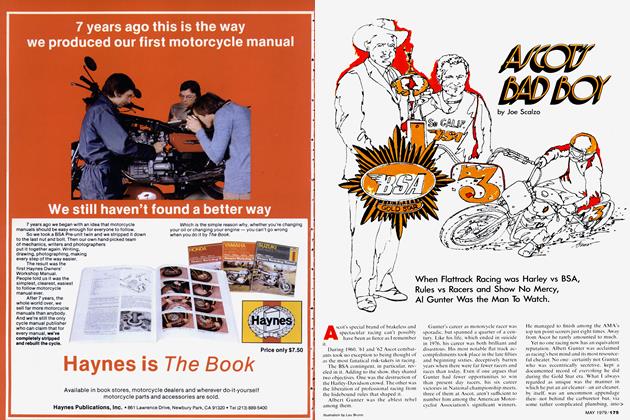

Then, two races later at Sturgis, AÍ Gunter really mucked things up by winning a Gold Star’s first-ever national.

Having been defeated in an unheard-of five nationals, H-D vowed never to let that happen again and, sure enough, Ks won 15 of I955’s 17 nationals and every race in 1956. So it was a shock when the veteran windmill-tilter and rebel sharecropper’s son from Huey Long Louisiana, Gunter, suddenly roused the tournament by strongly challenging Milwaukee and Finishing the 1957 standings just 6 points behind the ever-dominant Killer Joe. But Albert tore up his leg in the process; winded and worn-out, he afterward watched his career hit the skids. He had paid the price of being a windmill-tilter.

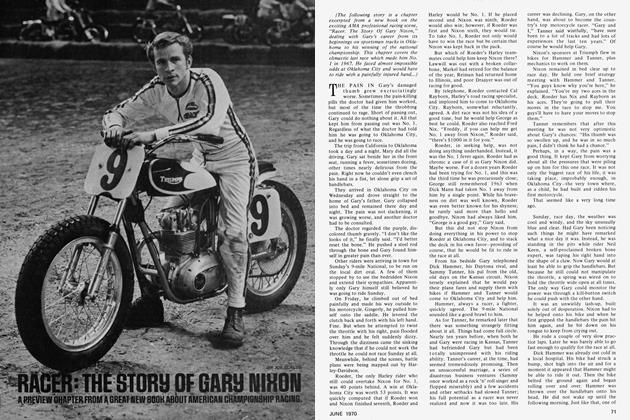

Our boy Klamfoth became the next thorn in the Vibrator armor; for a time, Dick even had Mooch Resweber going. After starting out on a Shooting Star and not much liking the way it carbureted, Dick reinvented himself into the greatest Gold Star supremo since Gunter. For two campaigns running, he won the nationals at Heidelberg, Pennsylvania, and Columbus, Ohio, the latter a difficult black-groove half-mile where H-D never lost and the storied Mooch was defending champion. Yet Dick did it to Resweber at Columbus in 1958 and then really royally in ’59, when he put on a chrome-plated tour de force. Showing up with a tender back he'd corkscrewed just the week before, Dick gingerly mounted up and then proceeded to jet into a lead of 200 feet on the opening lap. And then spend all his remaining laps performing the impossible pronatc-the-front-whcel cornering trick. Resweber afterward looked at him oddly, as if thinking, Who do you think you are, me?

The next national was out on the Left Coast at the Sacramento Mile. Dick, after a halfway decent showing there, found himself leading the AMA standings in the week between Sacramento and the Saturday-night half-mile match at L.A.’s just-built Ascot Speedway. Dick’s chances looked surprisingly good. He’d raced well at Ascot in the past, and ran a strong heat race qualifying for the national.

But his nifty new bubble faccshield malfunctioned, setting itself on “Open,” so Dick had to live the double nightmare of flying blind without eye protection plus having friendly Don Hawley snapping at his right and left elbows for the entire race. And while Dick was lurching about in the caboose, Ascot was being won in a stirring upset by the upstart Triumph of tiny Sammy Tanner, the crooner-cum-fiattracker who brought a T100 off the back row with impossible outside breakaway moves.

Klamfoth’s Ascot miscue was costly. Resweber next won Springfield, St. Paul and yet another Grand National seasonal title. A close third in points in 1958, Klamfoth stumbled back to fourth in '59. Trouble-prone Dick “Bugsy” Mann, second in ’59 points to Mooch, replaced Klamfoth as windmill-tilter-in-chief.

Four seasons later, in 1963, back at Ascot, Bugs was as usual half-dead from injury and fight, but still managed to become the first windmill-tilter to rupture nine unbroken years of Milwaukee stranglehold and capture the Grand National Championship.

Klamfoth was by then in semi-retirement, a distinguished veteran running at his late last best. Finally pushing his luck too far chasing the Harleys, he’d had Bart Market come after him on a kamikaze mission at Mansfield, Ohio, in 1960 (Black Bart got suspended), and at miserable Lincoln, Illinois, had been in the middle of the huge wreck that changed Grand National racing in 1962.

Going out for practice in a clump of riders that included Resweber, Jack Ghou!sen and four others, Dick disappeared into a cloud of dust blinder than Daytona's sand. He never emerged from it. Nor did anybody else.

Somebody unloaded and brought down the lot, including Dick, who landed all wrong and was on the receiving end of extremely serious hurts that included three compressed vertebrae. He and the corpse of Ghoulsen were thrown into the back of the same blood wagon, but Resweber-who’d been on schedule to wrap up his fifth-consecutive Number Onc-was in such dire shape he required an ambulance of his own. For two weeks he and Dick were imprisoned together in the same wretched little hospital, Klamfoth in traction and Resweber deranged with the pain of a leg almost wrenched off and the knowledge that he was facing years of rehabilitation and that his unequalled career was at end. Nobody-not the AMA, not Harley-Davidson-stepped in to pick up the diabolical hospital bills. It was a terrible ending for Mooch.

O nce bitter adversaries, Dick and Mooch in 2001 get drunk together at hall of fame festivities honoring them while the modern generation skeptically examines the crusty duo and privately wonders how such old buzzards could ever have engaged in such mad racing. Or, in Kiamfoth's case, arguably been the ultimate windmill-tilter.

Curious myself, during a recent telephone con versation, I praised Dick for being the all-time biggest Harley-Davidson hater. He asked what I meant. Well, I pointed out, even the diehard likes of Bobby Hill, Al Gunter and Bugs Mann had played the go-along-to-get-along game and occasionally raced Vibrators, but he never did.

Whereupon Dick monumentally surprised me by correcting the record and declaring that he'd never had anything against H-D, had always admired its racing team and at one time had almost agreed to join it.

"But," he went on, "something inside me made me say, `No, I don't want to do this." It was bad news for Harley, but good news for racing. And for Dick. He got to lead one of the top U.S. motorcycle-racing careers, and as a windmill-tiller deluxe be part of one of the hottest competition sagas of the departed century.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAfter the Fall

November 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFirst Bikes

November 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupSneak Peek! 2003 Ducati Multistrada

November 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupOld Pro, New Suspension

November 2001 By Allan Girdler