Indian Album

One family’s snapshots celebrate 100 years of America’s First Motorcycle

DAVID EDWARDS

THEY STARE BACK AT US FROM ACROSS THE DECADES, sepia-toned snapshots that have now become artifacts of a different time, a different America. Never before published, they document one family’s love affair with the Indian motorcycle, first built in 1901, earliest of the grand old marques of American motorcycling.

That the photographs were made in the first place is due to Harry Glenn Sr., family patriarch, Indian boardtrack hero and “road man” for the company, setting up and servicing dealerships throughout the Southeast.

Along the way, “Smiling Harry” recorded everything on film-the bikes, the shops, the racers and the everyday riders that made up motorcycling in the early part of the last century. As a slice of two-wheeled life, the Glenn family album is a priceless collection.

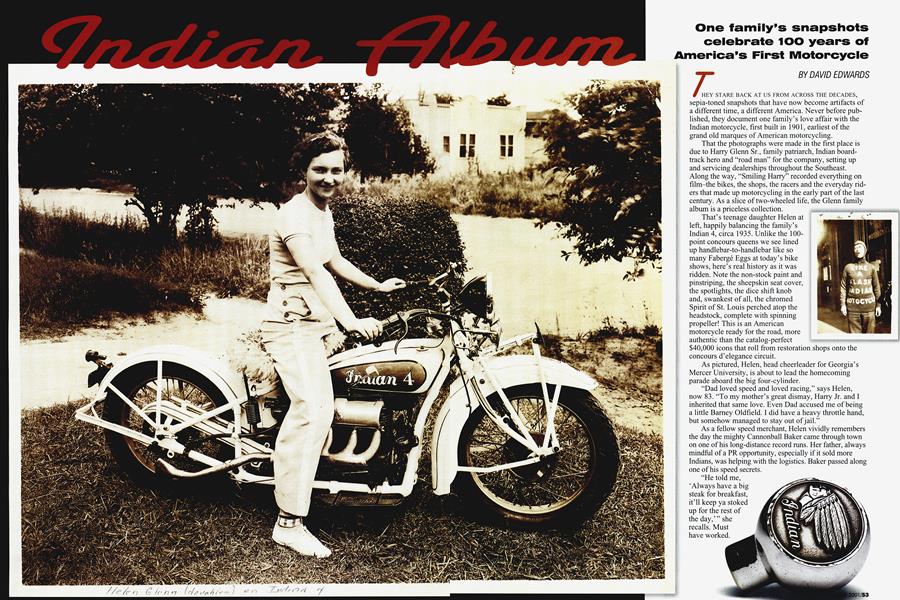

That’s teenage daughter Helen at left, happily balancing the family’s Indian 4, circa 1935. Unlike the 100point concours queens we see lined up handlebar-to-handlebar like so many Fabergé Eggs at today’s bike shows, here’s real history as it was ridden. Note the non-stock paint and pinstriping, the sheepskin seat cover, the spotlights, the dice shift knob and, swankest of all, the chromed Spirit of St. Louis perched atop the headstock, complete with spinning propeller! This is an American motorcycle ready for the road, more authentic than the catalog-perfect $40,000 icons that roll from restoration shops onto the concours d’elegance circuit.

As pictured, Helen, head cheerleader for Georgia’s Mercer University, is about to lead the homecoming parade aboard the big four-cylinder.

“Dad loved speed and loved racing,” says Helen, now 83. “To my mother’s great dismay, Harry Jr. and I inherited that same love. Even Dad accused me of being a little Barney Oldfield. I did have a heavy throttle hand, but somehow managed to stay out of jail.”

As a fellow speed merchant, Helen vividly remembers the day the mighty Cannonball Baker came through town on one of his long-distance record runs. Her father, always mindful of a PR opportunity, especially if it sold more Indians, was helping with the logistics. Baker passed along one of his speed secrets.

“He told me,

‘Always have a big steak for breakfast, it’ll keep y a stoked up for the rest of the day,’ ” she recalls. Must have worked.

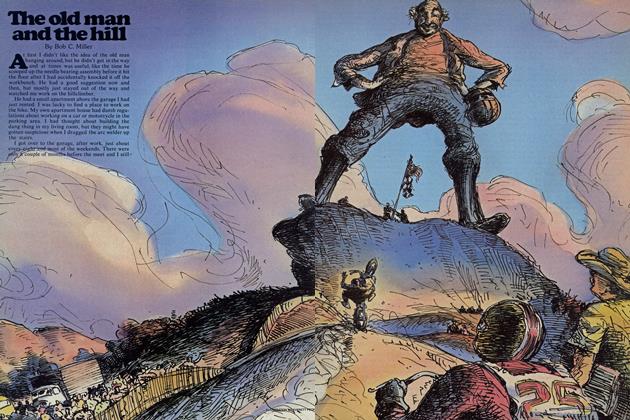

VI#ONE SINCE 1962, HARRY Glenn was one of the daring young men who whistle-stopped around the country risking life and limb on the board-track “murderdromes” of the day. That’s him on Lucky 13, all padded up, ready for the pummeling about to be meted out during a dirt-track endurance event-they sometimes ran 200 or 300 miles at a whack. That’s Harry, too, center of photo, behind the Indian tracker, clowning with his pals for the lensman in 1914 at the Atlanta motordrome. It's not hard to imagine, three years later, young men like these striking similar poses next to a Nieuport or Spad, about to engage in dog fights above the killing fields of the Western Front. Either vocation, the mortality rate was abominable.

Glenn had his brush with the reaper, a bad crack-up on a dusty, bump-strewn track in Kansas. At last coming to from a coma, he was reminded by his young wife that as a family man perhaps it was time to hang ’em up.

Indian was pleased to employ their likeable ex-racer as a district representative, servicing his native South. Helen Glenn remembers taking a year off grade school while the family traipsed around Florida spreading the Indian gospel. A tidy Chief sidecar with distinctive disc wheel covers was Harry’s calling card, adding credibility to his sales spiel.

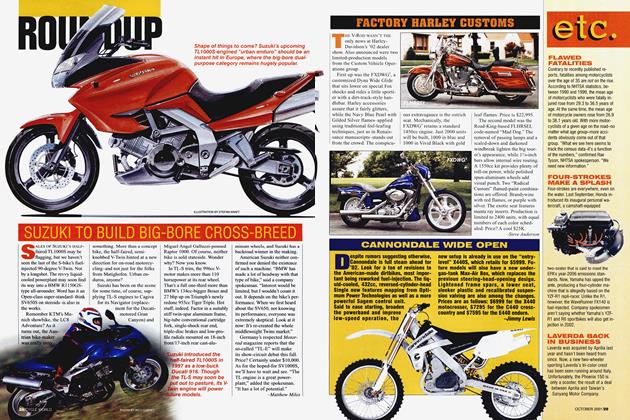

Back in those early days, dealerships were set up on a catch-ascatch-can basis, everywhere from converted general stores to proper brick edifices to tiny hardware stores, where the bikes were sold alongside ¿0Bjjk brooms, dustbins and wood-burning stoves.

LENN KNEW THE VALUE OF custómer relations, which is why he made so many photos of riders with their machines-of course, if the Indian logo made its way into the picture, so much the better.

The series above was made at Ross Rivers’ dealership in Columbia, South Carolina, and enthusiasm couldn’t contend with the Great Depression. Indian production plummeted from a high of

32,000 in 1913 to a paltry 1700 after the stock market crashed. People couldn’t afford motorcycles, but they could come up with 10 cents for a movie ticket, so Glenn reluctantly moved on to a company that built and ran

motion-picture theaters. “But he never gave up his love of motorcycles,” says daughter Helen. includes two dashing female riders, looking very much like low-level Amelia Earharts in I their riding togs.

And just - because he retired I from racing, don’t think Harry lost his edge. Caught in the rnrnrnrnrn^mmmmmflashbulb’s glare, he’s just climbed the “stony” side of Georgia’s Stone Mountain, his passenger looking thankful for the extra anti-bottoming provided by the spare tire. Unfortunately, even Harry’s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue