Vindian

The Chief that might have saved Springfield

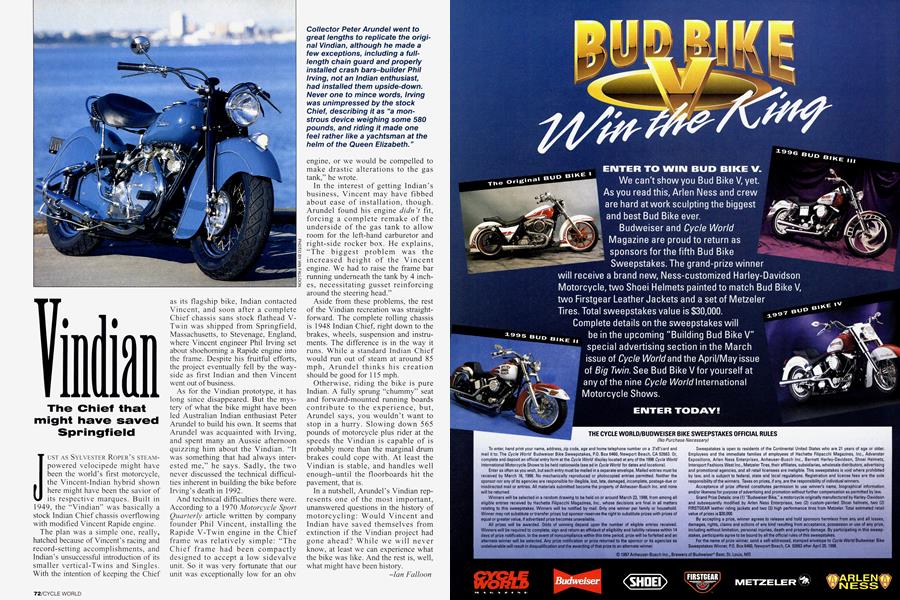

JUST AS SYLVESTER ROPER’S STEAMpowered velocipede might have been the world’s first motorcycle, the Vincent-Indian hybrid shown here might have been the savior of its respective marques. Built in 1949, the “Vindian” was basically a stock Indian Chief chassis overflowing with modified Vincent Rapide engine.

The plan was a simple one, really, hatched because of Vincent’s racing and record-setting accomplishments, and Indian’s unsuccessful introduction of its smaller vertical-Twins and Singles. With the intention of keeping the Chief as its flagship bike, Indian contacted Vincent, and soon after a complete Chief chassis sans stock flathead VTwin was shipped from Springfield, Massachusetts, to Stevenage, England, where Vincent engineer Phil Irving set about shoehoming a Rapide engine into the frame. Despite his fruitful efforts, the project eventually fell by the wayside as first Indian and then Vincent went out of business.

As for the Vindian prototype, it has long since disappeared. But the mystery of what the bike might have been led Australian Indian enthusiast Peter Arundel to build his own. It seems that Arundel was acquainted with Irving, and spent many an Aussie afternoon quizzing him about the Vindian. “It was something that had always interested me,” he says. Sadly, the two never discussed the technical difficulties inherent in building the bike before Irving’s death in 1992.

And technical difficulties there were. According to a 1970 Motorcycle Sport Quarterly article written by company founder Phil Vincent, installing the Rapide V-Twin engine in the Chief frame was relatively simple: “The Chief frame had been compactly designed to accept a low sidevalve unit. So it was very fortunate that our unit was exceptionally low for an ohv engine, or we would be compelled to make drastic alterations to the gas tank,” he wrote.

In the interest of getting Indian’s business, Vincent may have fibbed about ease of installation, though. Arundel found his engine didn’t fit, forcing a complete remake of the underside of the gas tank to allow room for the left-hand carburetor and right-side rocker box. He explains, “The biggest problem was the increased height of the Vincent engine. We had to raise the frame bar running underneath the tank by 4 inches, necessitating gusset reinforcing around the steering head.”

Aside from these problems, the rest of the Vindian recreation was straightforward. The complete rolling chassis is 1948 Indian Chief, right down to the brakes, wheels, suspension and instruments. The difference is in the way it runs. While a standard Indian Chief would run out of steam at around 85 mph, Arundel thinks his creation should be good for 115 mph.

Otherwise, riding the bike is pure Indian. A fully sprung “chummy” seat and forward-mounted running boards contribute to the experience, but, Arundel says, you wouldn’t want to stop in a hurry. Slowing down 565 pounds of motorcycle plus rider at the speeds the Vindian is capable of is probably more than the marginal drum brakes could cope with. At least the Vindian is stable, and handles well enough-until the floorboards hit the pavement, that is.

In a nutshell, Arundel’s Vindian represents one of the most important, unanswered questions in the history of motorcycling: Would Vincent and Indian have saved themselves from extinction if the Vindian project had gone ahead? While we will never know, at least we can experience what the bike was like. And the rest is, well, what might have been history.

Ian Falloon

View Full Issue

View Full Issue