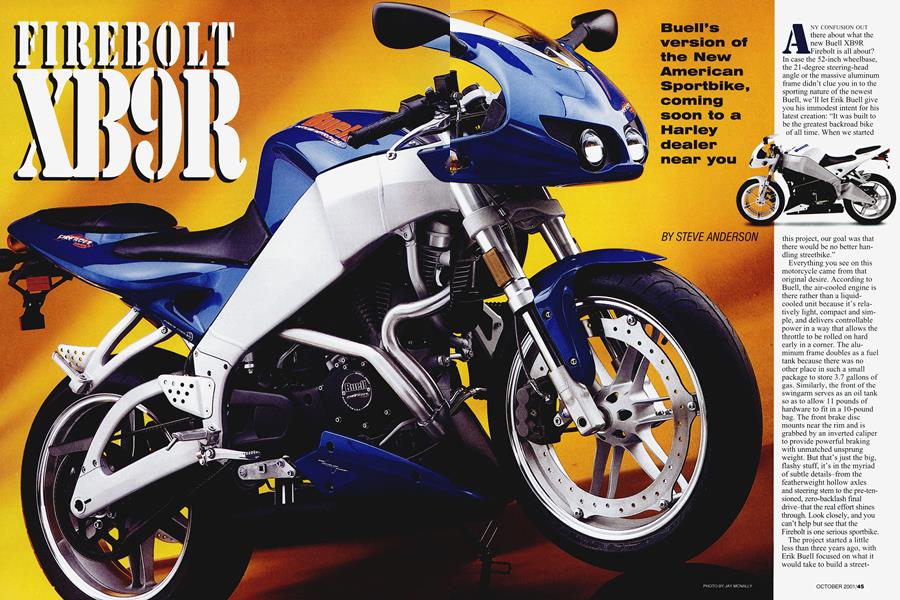

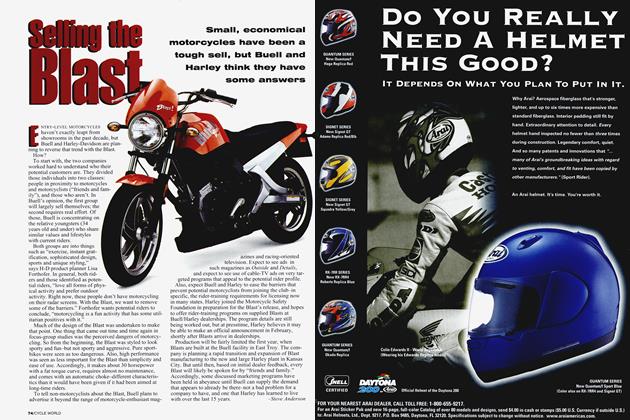

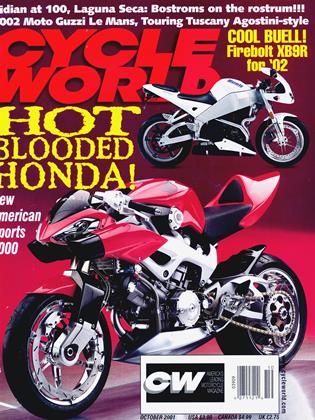

FIREBOLT XB9R

Buell’s version of the New American Sportbike, coming soon to a Harley dealer near you

STEVE ANDERSON

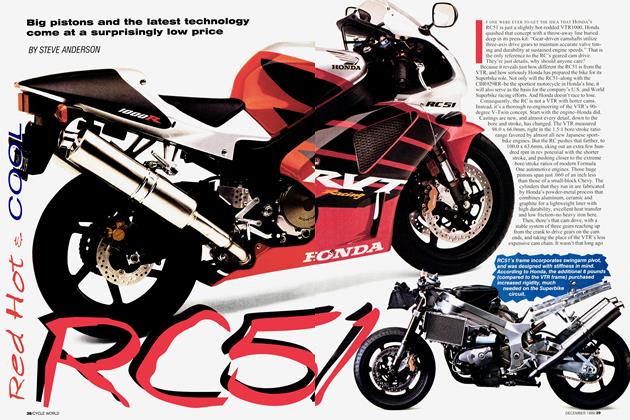

ANY CONFUSION OUT there about what the new Buell XB9R Firebolt is all about? In case the 52-inch wheelbase, the 21 -degree steering-head angle or the massive aluminum frame didn’t clue you in to the sporting nature of the newest Buell, we’ll let Erik Buell give you his immodest intent for his latest creation: “It was built to be the greatest backroad bike of all time. When we started this project, our goal was that there would be no better handling streetbike.” The project started a little less than three years ago, with Erik Buell focused on what it would take to build a streetbike with truly superlative handling. “The idea,” Buell says, “was to get a machine the size of Max Biaggi’s 250 GP bike, but with a lOOOcc, big-torque engine.” Such a machine could compete with Japanese middleweights (600s and 750s) in the marketplace, as well as more traditional European Twins.

Everything you see on this motorcycle came from that original desire. According to Buell, the air-cooled engine is there rather than a liquidcooled unit because it’s relatively light, compact and simple, and delivers controllable power in a way that allows the throttle to be rolled on hard early in a comer. The aluminum frame doubles as a fuel tank because there was no other place in such a small package to store 3.7 gallons of gas. Similarly, the front of the swingarm serves as an oil tank so as to allow 11 pounds of hardware to fit in a 10-pound bag. The front brake disc mounts near the rim and is grabbed by an inverted caliper to provide powerful braking with unmatched unspmng weight. But that’s just the big, flashy stuff, it’s in the myriad of subtle details-from the featherweight hollow axles and steering stem to the pre-tensioned, zero-backlash final drive-that the real effort shines through. Look closely, and you can’t help but see that the Firebolt is one serious sportbike.

From the beginning, the idea of a short-stroke revamp of the Sportster-based Buell engine was part of the program, but the final aluminum frame was not. “We were originally going to do a tube frame,” says Vance Strader, engineering lead on the chassis team, “but every design we tried always left one component out. It was either the gas tank, the shock or the airbox-we couldn’t fit it all in the 52-inch package.” So instead of abandoning the 250 GP size, Erik suggested resurrecting a design he had done in 1989 for an unproduced prototype, one that wrapped huge beams around the engine, and used all the volume inside the beams to replace the fuel tank. That was the key that finally allowed the Firebolt package to come together. The massive-appearing frame holds fuel in an “O” (looking down from the top) around the engine, with the fuel filler immediately behind the steering head. Fuel resides in the box formed behind the steering head, in the side beams themselves and in a large cross member behind the engine. Fabricated by Italian frame specialist Verlicchi (maker of Bimota, Ducati and some BMW frames) from aluminum sheet and castings, the structure allows the Firebolt to be both compact and, as Buell himself describes it, “obscenely stiff.”

Similarly, the swingarm now carries oil, an idea that dates back to the early tube-frame designs for the Firebolt. The elaborate swingarm casting is by Brembo, and carries 3 liters of oil in the box behind the swingarm pivot. The arms themselves are oil-free, and actually have open sections facing the tire. Because the oil is carried close to the pivot, the effect on unsprung weight is minimal, and early testing at Buell actually indicated a couple of pleasant benefits: Suspension movement acts to de-aerate the oil, and the large mass of aluminum helps bring oil temperature down.

If you were to look at the short wheelbase and steep steering head and wonder if the Firebolt is a twitchy, unstable beast, you wouldn’t be the first. But Buell and his engineering staff assure that the Firebolt is anything but that. “It’ll turn inside anything...” says Strader, “...without scaring you,” pipes in Tim Osterberg, overall engineering head of the project. According to Buell, there’s no one feature that makes the machine’s handling work; instead, it’s the whole design. The steep steering head and compact 45degree V-Twin are both part of it, with the engine being positioned as far forward as possible, putting 52 to 53 percent of the machine and rider’s weight on the front wheel. All else being equal, more weight on the front wheel makes for a more stable motorcycle. Erik’s pomographically rigid chassis is another factor. Buell has been measuring the overall stiffness of racing and competitive sportbikes for years, and claims the Firebolt stands out. “It’s not just the frame stiffness; it’s the specific stiffness over the whole wheelbase length,” he says.

“That gives you instant response and minimizes resonances.”

Some of the XB9R’s handling prowess comes from the distribution of mass. “Full of fuel,” says Buell, “it has a lower center of gravity than a Yamaha R6.” Every major mass is moved as close to the center of gravity as possible for quick roll rates and improved damping ratios. Erik has once again put the heavy muffler under the engine, “where it belongs.” Fie simply can’t understand why anyone would locate such weighty parts back by the rear wheel, tradition or no.

More of the handling combination comes from low unsprung weight and the high-quality Showa suspension fitted to the machine. The front wheel is truly exceptional.

Freed from braking torque by the inverted rotor, the spokes are minimal, and the wheel itself weighs just 9 pounds-an aluminum part lighter than most magnesium racing wheels. The Showa suspension runs the

Japanese company’s best, fully adjustable dampers, and the rear shock-no longer under the engine-now works conventionally in compression and without a linkage, just as on every Honda CBR600.

But a substantial part of the handling package with the Firebolt is the engine itself. It’s not the “Twin Blast” some of the internet rumor sites were describing, nor is it simply an uprated Sportster-the changes are far more extensive than that. Instead, think of it as the best sport engine that can be built on Harley’s existing Capital Drive tooling, helping keep the Firebolt list price under $10 grand, instead of the $17,000 of the Harley-Davidson V-Rod with its new liquid-cooled powerplant.

Because the Firebolt was conceived as a realworld sportbike, and not a racerreplica, a broad powerband and tractable power were deemed more important than simply peak horsepower. According to Buell, “We wanted the best torque-to-weight ratio.” But he also wanted a higher-revving, lighter, sportier powerplant than existing Buell 1200 engines. The 7500-rpm capability of the Firebolt started with the adoption of the shorter 3V8-inch stroke of the Blast, keeping the same 3!/2 inch bore of the 1200. The short stroke reduced displacement to 984cc, but meant that the engine was still at reasonable piston speeds 2000 rpm above those of the 1200. “After that,” says Dan Grimes, the H-D engineer in charge of the engine, “we had to get rpm from the valve gear and fill the cylinder at high revs.” New cylinder heads with improved ports aided engine breathing, and new computer-designed cams (spinning in the opposite direction of Sportster cams, like a Blast) actually lift the valves 0.060-inch further than current XI cams, to 0.550inch. But the very special cam ramps, lighter valves with thinner stems and NASCAR-type spiral-wound springs actually move the onset of valve float all the way to 8000 rpm,

well beyond the 7500-rpm hard redline provided by the 984’s fuel-injection computer.

A huge muffler and airbox (roughly 11 liters each) quiet intake and exhaust with minimal restriction, and engine tuning was aimed at a smooth powerband. The torque curve is exceptionally flat, unlike that of any previous Buell, and the engine pulls near its 68-foot-pound peak torque from 4000 rpm to over 7000. At 7200, the engine peaks at 92 crank horsepower-figure 80 at the rear wheel. When asked if such a smooth powerband might make the bike feel slower than it measures, even as it makes the bike easier to ride, Buell snaps back, “This isn’t for some geeky kid who wants to scare himself; this is for someone who wants to really go fast.”

Many additional changes are aimed at improving the reliability or usability of the Firebolt engine. New pistons and rods are lighter and stronger, as are the engine cases themselves. As with the Blast, the Firebolt’s cases incorporate the swingarm-pivot mounts, and discard cosmetic fetishes such as the front oilfilter mount that mimics a classic generator on the Sportster. The engine diet cut its poundage (even with swingarm-pivot mounts) from 210 pounds to 178.

That Harley Engineering had completed work on the Twin Cam 88 by the time the 984 project started freed up the special motoring dyno used for the Twin Cam’s oil-system development. The same capability for internal pressure mapping and high-speed photography became available to really understand what was happening to lubricant inside the 984. “We wanted to get oil in the right places and get it out,” says Grimes.

He points to the new,

tiny reed-valve between the cam chamber and the crankcase proper as being the key to

depressurizing the bottom end, and pulling oil quickly from the heads.

“The reduction of oil in the engine noticeably improves power,” says Grimes. More recent Harley lessons were applied to the gearbox. Long a source of complaint on Buells for high shift effort and long throws, the Sportster tranny bequeathed only its gearsets to the 984. A new shift mechanism with shift forks running on dual rails rather than the shift drum was devised, with its benchmark being the

Kawasaki ZX-6R—in Harley testing, the Japanese 600 with the best shift quality. The new system uses a low-inertia aluminum drum actuating the shift forks through needle-bearing-fitted followers. Even clicking through the gears by hand on the Firebolts displayed at the Harley dealer show indicates that Buell has entered

a new world of shift quality.

The final part of the powertrain may actually be the most important innovation of all: the zero-backlash final drive. The latest Gates Polychain belts are so dimensionally stable as to not require adjustment (and none is provided on the Firebolt), but Gates does recommend running its belts preloaded—commonly done on industrial equipment but never before on a motorcycle. Because the center of gravity of the Firebolt is so low, a fair amount of swingarm droop was required to get the anti-squat geometry (see TDC, this issue) that keeps the Firebolt level under acceleration. So much droop, in fact, that there was an excess amount of belt slack over part of the suspension travel. The solution proved to be a very special fixed idler pulley.

Forty pages of calculations and computer code established one diameter and one location for the pulley that would keep belt tension almost constant through the entire range of rear suspension movement. With constant tension it became possible to preload the belt to the 350 pounds recommended by Gates. The result? No backlash in the final drive at all-and one more piece of the puzzle of how to connect the rider’s brain more directly to what’s happening at the tire contact patches.

Keeping its street rather than race mission in mind, Buell designers gave the Firebolt a riding position more CBR600 than GSX-R. The overall quality of the Firebolt prototypes displayed at the dealer show was a substantial cut above any previous Buell, and the emphasis in the design stage was to create a product that could be manufactured easily and accurately. A good example is the new rubber enginemounting system, which uses non-adjustable forged links for its locating tie-rods, allowed by machining the rod mounts very precisely on both frame and engine. An extremely aggressive test program, claims Buell, has caught problems experienced by only the one-in-a-thousand hard or abusive rider, and allowed even those to be corrected before manufacturing begins this fall.

Will the Firebolt be the ultimate backroad bike of Erik Buell’s intent? Only riding it will answer that question, but the combination of a machine with the size of a 250 and the smooth, well-flywheeled power of its big V-Twin engine certainly promises to make the Firebolt a giant-killer of the new millenium, a machine whose distinctive face no one will want to see gaining on them in their rearview mirrors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue