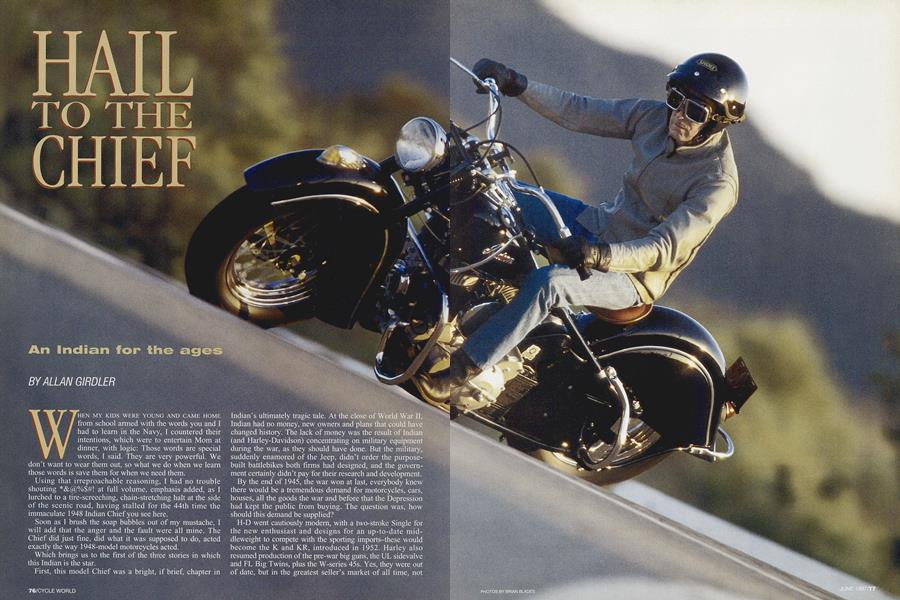

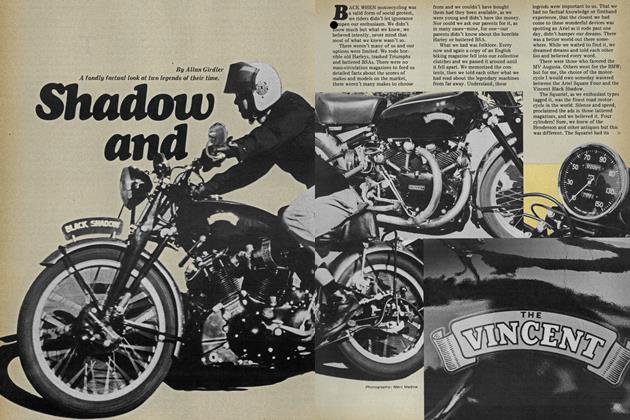

HAIL TO THE CHIEF

An Indian for the ages

ALLAN GIRDLER

WHEN MY KIDS WERE YOUNG AND CAME HOME from school armed with the words you and I had to learn in the Navy, I countered their intentions, which were to entertain Mom at dinner, with logic: Those words are special words, I said. They are very powerful. We don’t want to wear them out, so what we do when we learn those words is save them for when we need them.

Using that irreproachable reasoning, I had no trouble shouting *&@%$#! at full volume, emphasis added, as I lurched to a tire-screeching, chain-stretching halt at the side of the scenic road, having stalled for the 44th time the immaculate 1948 Indian Chief you see here.

Soon as I brush the soap bubbles out of my mustache, I will add that the anger and the fault were all mine. The Chief did just fine, did what it was supposed to do, acted exactly the way 1948-model motorcycles acted.

Which brings us to the first of the three stories in which this Indian is the star.

First, this model Chief was a bright, if brief, chapter in Indian’s ultimately tragic tale. At the close of World War II, Indian had no money, new owners and plans that could have changed history. The lack of money was the result of Indian (and Harley-Davidson) concentrating on military equipment during the war, as they should have done. But the military, suddenly enamored of the Jeep, didn’t order the purposebuilt battlebikes both firms had designed, and the government certainly didn’t pay for their research and development.

By the end of 1945, the war won at last, everybody knew there would be a tremendous demand for motorcycles, cars, houses, all the goods the war and before that the Depression had kept the public from buying. The question was, how should this demand be supplied?

H-D went cautiously modem, with a two-stroke Single for the new enthusiast and designs for an up-to-date middleweight to compete with the sporting imports-these would become the K and KR, introduced in 1952. Harley also resumed production of the pre-war big guns, the UL sidevalve and FL Big Twins, plus the W-series 45s. Yes, they were out of date, but in the greatest seller’s market of all time, not

many buyers (or sellers) cared.

The guys at Indian cared. The previous team, major stockholder E. Paul du Pont (yes, of those du Ponts) and canny execs Joe Hosley and Allan Carter, had planned to revive the sporting Scout, replace the aging Four with a modular design and civilize the 90-degree Model 841 transverse V-

Twin that formed the basis for the military project. But Hosley died and du Pont’s health wasn’t good, besides which he’d lost a lot of money, so he sold his shares and retired, while Carter went off to become a Harley dealer.

The new owners knew business and they knew marketing and manufacturing. What they didn’t know was motorcycles. They liked them, though, and they looked around and noticed that lots of Americans were buying lightweight

British imports, motorcycles very different from the hulking U.S. models of that and earlier days.

So Indian put all its eggs in one basket, the modem lightweight market. They spent R&D money on new designs and they spent the advertising budget in mass media, inviting new people into the sport. Unfortunately, in all this hubbub, the new team ignored the shaft-drive Model 841 and a prototype-stage inline-Four that was hanging about. Worse, they ditched the still-popular Sport Scout-the dealers literally stormed the board of directors’ meeting over that one.

While the lightweight future was being dragged over the horizon, Indian had to do something to appease dealers (and keep the plant busy), so in 1946 it resumed production of the oldest and arguably most Indian of all Indians, the Chief.

The name and the basic design of the Chief date back to 1922. It began as a 61-cubic-inch, 42-degree V-Twin, then grew to 74 inches in 1923. But all the rest-as in rigid frame, sidevalves, kick start, three speeds, hand shift and foot clutch-was retained. It would be another 17 years until the 1940 model sprouted the classic skirted fenders that gave the Chief one of motorcycling’s all-time most distinctive shapes.

To hearty applause from the dealers-and the buyers, one need scarcely add-Indian sold all the ’46 Chiefs it could make, almost 7000 of them.

Post-war Chiefs retained the plunger rear hub-another 1940 addition-one of suspension design’s less-useful ideas, and adapted the girder fork first seen (with Indian anyway) on the military project. The 1948 version gained a sealedbeam headlight and an improved oil pump, one that provided a steady supply against the previous pump’s habit of switching from not enough to way too much. And the ’48 had a new and larger speedometer, driven off the front hub.

Sad note here is that the 1948 Chief is one of the more rare versions. Indian only made a handful, despite the clamor from the dealers. At the time, all emphasis was on the new lightweights, the 220cc Arrow Single and the 440cc Scout vertical-Twin. These were handsome bikes and fairly radical for the time, as in overhead valves, full hydraulic suspension, foot shift, etc. Tragic, then, that they were woefully under-engineered and failed disastrously, which as we know now, led to the eventual death of Indian. It would take another decade or so and Soichiro Honda for the lightweight to become a force in American motorcycling.

So, what we had in 1948 with the Model 348 Chief, then, was kind of an instant classic. This begins the second part of our story, the history of this particular Indian, engine number CDH-5095-B, frame number 348-5095.

This machine’s history runs backward, more like an autopsy. It’s a safe inference that it was sold new in 1948. It reappeared, for our purposes at least, in March, 1993, when a collector bought it from a Harley-Davidson dealer in South Dakota, asking price $7000. The good news was the Chief was remarkably complete. All the stock fasteners, the nuts and bolts, were just as they’d been in 1948. The Indian tractor-style saddle was still there, large and cushioned with an adjustable spring inside the seat post. All the Chiefs

body parts were intact; nobody had chopped it or stripped it. The paint was even a stock Indian color, Prairie Green (due to the DuPont Paint connection, Indian had a wide choice of artistic and inventive colors on offer).

In short, it looked to be an easy restoration. But the finder, a busy man with other projects, never got

around to the task. Enter Jerry Greer, owner of Indian Engineering in Stanton, California (714/826-9940), who bought the Chief after the usual round of haggling.

Greer knows there’s no such thing as an easy restoration, though, especially when the machine in question is a halfcentury old. OT 5095 had been rode hard and put away wet, as they say in Texas. The odometer had quit recording at 10,472 miles, but an engine strip hinted at actual mileage two or three times that, evidenced by a disintegrated piston and cylinder bores two sizes over.

Also, a nut had come loose in the clutch and allowed the exposed end of the kickstart shaft to become a milling machine, so to speak, and bore a half-inch-diameter hole right through the chainguard. “Noise can’t have been a concern,” Greer notes, adding that when the shaft finally

worked its way through, the then-owner might have been pleased, because he finally knew where the howling noises were coming from.

A missing spring had converted the sidestand into a trailing curb feeler, and the paint wasn’t entirely stock after all. Greer’s research revealed that at one time Indian offered factory paint in spray cans. The Prairie Green had been added this way, atop the first stock paint, which had been Sea Foam Blue.

Further archaeological digging divulged that the bike had, in effect, two distinct sides, bifiircated at an odd angle, with the rust/grunge/grease different from one side to the other. Greer’s best guess is that 5095 spent years in the country, leaned against a bam, one half beneath an eave, the other half extending beyond shelter. Every fall, the first blue-norther covered the bike in snow, and it stayed covered all winter. During spring and summer, the out half got rained on and dripped on and baked, and the inner half didn’t. Factor in years of accumulated crud, and 5095 was, in sum, a full, complete and total restoration in need of the right person to make it happen.

Cue John Anderson, wealthy health-products manufacturer, a man with the enthusiasm and the resources for the task. He’s also willing to risk offending convention. For the most obvious example, refer to the restored Chiefs black paint. >

Quoting Greer: “If you want to sell an Indian, paint it red. If you want to keep an Indian, paint it white.”

Why is that?

“Because 90 percent of Indians sold today are red. We called it ‘retail’ red, it’s more of a maroon. But nobody will buy one if it’s white.”

Oh.

“Now, if you want people to gasp, paint it black.” Obviously, Greer and Anderson wanted people to gasp. Both men also agree that motorcycles are supposed to be ridden, that just because we’re looking at close to 35 big ones fully restored is no reason not to use the Chief as a motorcycle instead of a museum piece.

And that gets us to the third segment of the story. This is the personal part.

That’s because this reporter was the dumbest kid ever delivered to this unprepared planet. When I was 17, my best pal asked me to come with him to look at a motorcycle, his theory being two heads would be better than one, never mind that two times nothing, which is what we knew about motorcycles, is still nothing.

Make that less than nothing. He jumped on the kick lever with the engine in gear, the engine fired and the bike jumped into and up the owner’s garage wall.

My pal thoughtfully cushioned the crash with his body and the motorcycle wasn’t hurt. He immediately lost interest, but I was enthralled and came up with the asking price, $50, and wobbled down the road to hide the machine in a neighbor’s barn-I was not dumb enough to tell my parents I’d bought a motorcycle.

What did I get? A 1934 Harley-Davidson VL, years older than I was ’cause nostalgia hadn’t been invented yet and in those happy days, old clunks were cheap and they were what kids like myself learned on.

The VL was a 74-inch sidevalve V-Twin, rigid rear, springer fork, hand shift and foot clutch, kick start when you couldn’t find a hill to park at the top of.

In sum, and never mind the calendar years, my first motorcycle was as close to this 1948 Chief as it’s possible to come without swapping badges.

Ride it, Mr. Editor Edwards told me, and tell us what it’s like.

Tough, is what it was like at first, which is where the aforementioned coarse language comes in. To begin, the starting drill: Full choke, three priming kicks with the ignition switch off, crack the throttle, retard spark, key on, kick with conviction and it fires. With spark still retarded so the engine slows and the gearbox doesn’t grind, push the gear lever forward, then ease the rocker clutch out...*&@%$#!

Stalled again. And again.

Blame it on that abominable foot pedal, which rocks at an angle with no consideration for the motion of the human, well, at least this human’s, ankle. Point your toe and shove, and the clutch is disengaged, easy enough. To engage, plant your heel on the rear pad and ease down...*&@%$#!

Memory may trick me here, but I don’t recall having this much trouble with my first bike-of course, I was too young to join the Navy then and didn’t know the right words yet.

But I learned, to ride this Chief I mean, as well as the right words.

Fear of mockery by traditionalists makes me add here that the normal Indian practice was to have the throttle on the left and the gear lever on the right, the opposite of H-D and others. But owner Anderson has a fleet of “normal” bikes and rides them, so it seemed prudent to fit this Chief with the optional rightside throttle and leftside stick, sparing me that additional learning experience.

Rocker clutch aside, the Chief has some nifty old-fashioned engineering. There’s no oil pressure gauge, for instance, and no warning light. Instead, while the engine warms, one pops the cap off the oil tank, at the right front, sharing space with the dual gas tanks. The return pipe is >

higher than the level in the tank. Peer into the tank and if oil is burbling out of the return line, the pump is working and all is well. Neat. And almost foolproof.

For the novice, or one who’s been away 40 years, deliberation is the key to stately, seamless progress. The sidevalve 74’s three forward speeds

are widely spaced and there is no gate for the shift, unlike the Flarley system. The pattern is first all the way forward, back to neutral, back again for second and then all the way back for third, carefully passing the spare neutral, as it were, between second and top. Once rolling, advance the spark on the left twistgrip (if you don’t, the engine heats up and the pipes blue...sorry, Jerry). Dial in power with the right hand, work the clutch and the shift lever carefully and firmly...ahhh, that’s it.

This is what motorcycling was and is supposed to be about, in 1948 and now. The Chief was made, literally and spiritually, for hills and highways that need to turn when they climb. Interstate highways were not invented then and need not apply now. There’s a wide sweet spot, 40 to 60 mph, where the engine is strong and makes just the right note and noise. The sprung saddle fits well, feels good and absorbs all the bumps the (minimal) suspension doesn’t notice. Whyever did we abandon the suspended, tractor-style seat?

The Chief is low, the suspension tight, the steering lovely-easy and clear and precise. Another observation: Older machines, designed when pavement wasn’t everywhere, are happier on dirt than any modern mega-cruiser can ever hope to be. Just for an experiment, I dirt-tracked the Chief, powered the back wheel loose, and it was so natural I did it with the restorer watching and he didn’t threaten death, not once.

The limits to this 1948 motorcycle come later. The brakes are fine at 1948 speeds, up to 55 or 60 mph. Ditto for the steering, even if the plunger rear suspension, an idea that was abandoned later, thank goodness, induces a weave that doesn’t happen until you’re going faster than the engine likes, thank goodness again.

But on a warm afternoon with the sun shining and the traffic elsewhere, one cannot imagine a motorcycle on which one could be having any more fun.

This Chief divides people into two types, as the saying goes. There are people who don’t notice. And there are people who are as entranced as I was on that fateful day when I was a teenager and first pushed a gear lever forward and eased a foot clutch back.

Oh. The punchline here is mystical.

Some 20 years ago, after times spent on Triumphs and Hondas, I rode an H-D Sportster and in a flash for which I was not prepared, I had an instant vision of the past, total recall. This was a Harley-Davidson, related by blood and sweat to my first Harley-Davidson, that old junker VL.

That moment didn’t occur this time. As mentioned, this Chief was as like my old Harley as a spec sheet can make it. And yet, somehow, the two were different. Maybe it’s those grand, flowing fenders, maybe it’s Indian’s own particular brand of flathead chuff-chuffing, maybe it’s the knowledge that you’re aboard one of the last examples of an American dream sadly gone awry.

How it works, I don’t know.

But long live the difference, I say. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue