The Perfect Motor?

Inline-Four or V-Twin, that’s the question

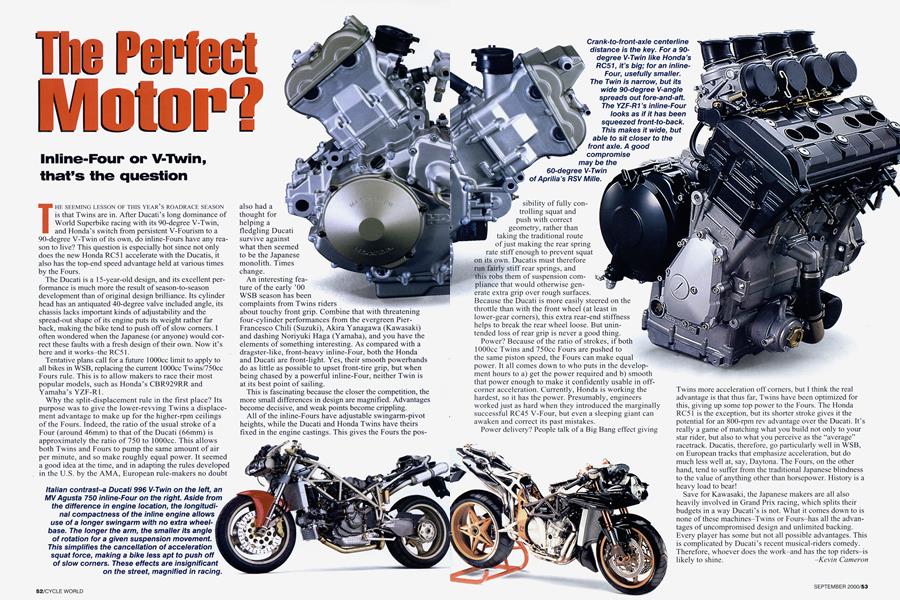

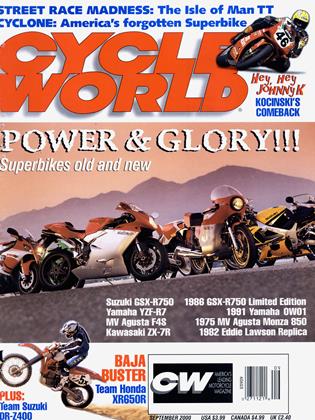

THE SEEMING LESSON OF THIS YEAR’S ROADRACE SEASON is that Twins are in. After Ducati’s long dominance of World Superbike racing with its 90-degree V-Twin, and Honda’s switch from persistent V-Fourism to a 90-degree V-Twin of its own, do inline-Fours have any reason to live? This question is especially hot since not only does the new Honda RC51 accelerate with the Ducatis, it also has the top-end speed advantage held at various times by the Fours.

The Ducati is a 15-year-old design, and its excellent performance is much more the result of season-to-season development than of original design brilliance. Its cylinder head has an antiquated 40-degree valve included angle, its chassis lacks important kinds of adjustability and the spread-out shape of its engine puts its weight rather far back, making the bike tend to push off of slow comers. I often wondered when the Japanese (or anyone) would correct these faults with a fresh design of their own. Now it’s here and it works-the RC51.

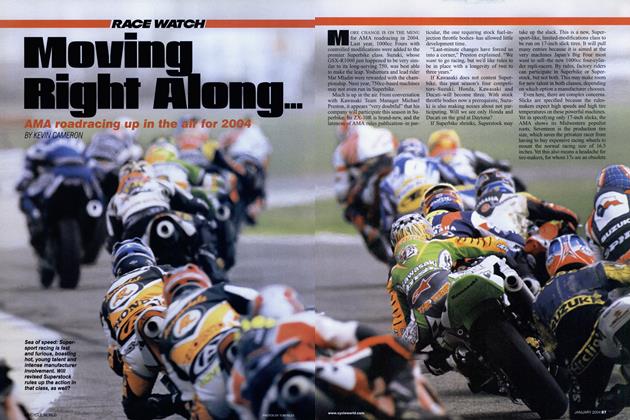

Tentative plans call for a future lOOOcc limit to apply to all bikes in WSB, replacing the current lOOOcc Twins/750cc Fours rule. This is to allow makers to race their most popular models, such as Honda’s CBR929RR and Yamaha’s YZF-R1.

Why the split-displacement rule in the first place? Its purpose was to give the lower-revving Twins a displacement advantage to make up for the higher-rpm ceilings of the Fours. Indeed, the ratio of the usual stroke of a Four (around 46mm) to that of the Ducati (66mm) is approximately the ratio of 750 to lOOOcc. This allows both Twins and Fours to pump the same amount of air per minute, and so make roughly equal power. It seemed a good idea at the time, and in adapting the mies developed in the U.S. by the AMA, European rule-makers no doubt also had a thought for helping a fledgling Ducati survive against what then seemed to be the Japanese monolith. Times change.

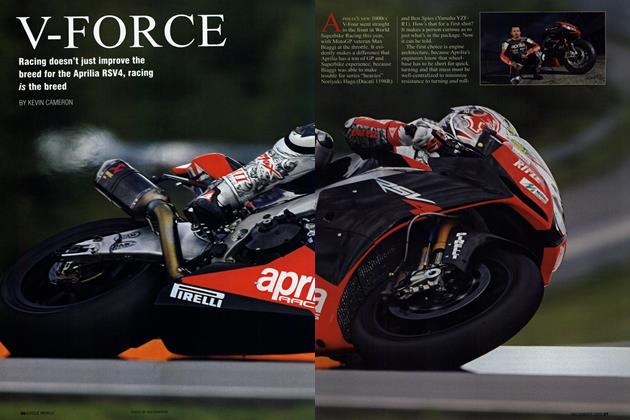

An interesting feature of the early ’00 WSB season has been complaints from Twins riders about touchy front grip. Combine that with threatening four-cylinder performances from the evergreen PierFrancesco Chili (Suzuki), Akira Yanagawa (Kawasaki) and dashing Noriyuki Haga (Yamaha), and you have the elements of something interesting. As compared with a dragster-like, front-heavy inline-Four, both the Honda and Ducati are front-light. Yes, their smooth powerbands do as little as possible to upset front-tire grip, but when being chased by a powerful inline-Four, neither Twin is at its best point of sailing.

This is fascinating because the closer the competition, the more small differences in design are magnified. Advantages become decisive, and weak points become crippling.

All of the inline-Fours have adjustable swingarm-pivot heights, while the Ducati and Honda Twins have theirs fixed in the engine castings. This gives the Fours the possibility of fully controlling squat and push with correct geometry, rather than taking the traditional route of just making the rear spring rate stiff enough to prevent squat on its own. Ducatis must therefore run fairly stiff rear springs, and this robs them of suspension compliance that would otherwise generate extra grip over rough surfaces.

Because the Ducati is more easily steered on the throttle than with the front wheel (at least in lower-gear comers), this extra rear-end stiffness helps to break the rear wheel loose. But unintended loss of rear grip is never a good thing.

Power? Because of the ratio of strokes, if both lOOOcc Twins and 750cc Fours are pushed to

the same piston speed, the Fours can make equal power. It all comes down to who puts in the development hours to a) get the power required and b) smooth that power enough to make it confidently usable in offcorner acceleration. Currently, Honda is working the hardest, so it has the power. Presumably, engineers worked just as hard when they introduced the marginally successful RC45 V-Four, but even a sleeping giant can awaken and correct its past mistakes.

Power delivery? People talk of a Big Bang effect giving Twins more acceleration off comers, but I think the real advantage is that thus far, Twins have been optimized for this, giving up some top power to the Fours. The Honda RC51 is the exception, but its shorter stroke gives it the potential for an 800-rpm rev advantage over the Ducati. It’s really a game of matching what you build not only to your star rider, but also to what you perceive as the “average” racetrack. Ducatis, therefore, go particularly well in WSB, on European tracks that emphasize acceleration, but do much less well at, say, Daytona. The Fours, on the other hand, tend to suffer from the traditional Japanese blindness to the value of anything other than horsepower. History is a heavy load to bear!

Save for Kawasaki, the Japanese makers are all also heavily involved in Grand Prix racing, which splits their budgets in a way Ducati’s is not. What it comes down to is none of these machines-Twins or Fours-has all the advantages of uncompromised design and unlimited backing. Every player has some but not all possible advantages. This is complicated by Ducati’s recent musical-riders comedy. Therefore, whoever does the work-and has the top riders-is likely to shine. -Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMr. Bonneville

September 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafé Americano

September 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

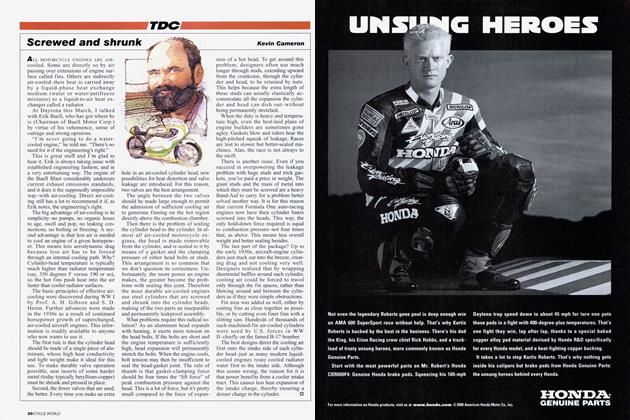

TDCScrewed And Shrunk

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Takes Charge

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Screamin' Little Thumper

September 2000 By Jimmy Lewis