ENIGMA MACHINE

Tracking down the world’s most collectible motorcycle, Lawrence of Arabia’s Brough SS100 death bike

MICHAEL JACKSON

IT IS THE SILKIEST thing...and at 50 mph she is a dream...if only the RAF gives me time enough...to use the poor thing...I am grateful for the care taken...to make her perfect.” Thus wrote Thomas Edward Lawrence, forever known as “Lawrence of Arabia,” to bikemaker George Brough in March, 1932. Lawrence was collecting his seventh and final Brough Superior-immediately christened “George VII”-direct from the works, a practice encouraged by the Nottingham company’s eponymous proprietor, who prospered on publicity accrued from supplying bespoke motorcycles to his well-heeled or, in Lawrence’s case, celebrated clientele.

This was TEL’s fourth SS100, the largest ohv model in the Brough range. He described the 200-mile journey home to Hampshire as “a very cold but beautiful ride,” during which he experienced nothing more serious than “an oiled back plug.” Over the next three years, Lawrence put 25,000 miles on the clock of George VII, a machine also called Boanerges, meaning “Son of Thunder.” Accurate records of his in-the-saddle average speeds and fuel consumption were maintained, giving totals of 43 mph and 50 mpg. Clearly, Lawrence was no slouch. Indeed, certain colleagues hinted prophetically that he was “an accident waiting to happen.” In April, 1934, with 19,000 miles on the odometer, he enjoyed informing Brough that "George VII is run ning like stink. . .and if you'd seen me dropping the county police. . .along New Forest Roads. . .you'd have been pleased with our performance." Unbridled enthusiasm for a 45-year-old. Little did Lawrence know that he had but one year left to live, and that he would die riding his beloved Boanerges...

That one of the 20th century’s truly charismatic figures should meet his end astride an example of the world’s most revered machine serves only to compound the mystique. From this unexplained accident, returning from a nearby post office on a bright sunny morning, have sprung a zillion conspiracy theories-JFK’s “magic bullet” has nothing on the Machiavellian schemes conjured up to explain the great man’s demise. Yet had Lawrence died upon an economy-model Enfield or an inexpensive BSA, his legend in some indefinable way would be diminished. After all, don’t we prefer Life’s Heroes be conveyed on Vincent-HRDs, Hendersons and Pierces, or some other famous marque? James Dean’s untimely demise in a Porsche is poignant illustration.

While linked with matters cinematic, it is significant how director David Lean, in his Academy Award-winning movie Lawrence of Arabia, chose to begin that epic with TEL’s crash sequence. Given that motorcycle historians have little faith in Hollywood’s ability to portray any internal-combustion event with accuracy, at least Columbia Pictures sourced a comparable model Brough (unfortunately it displayed George Vi’s registration number-a machine, incidentally, which Mr. & Mrs. George Bernard Shaw had gifted to Lawrence). The film’s chosen accident site, however, did not much resemble Bovington Heath’s tank-testing acres; a wild, windswept spot where, in his youth, this author competed in numerous motorcycle trials. Equally, whereas the lofty Peter O’Toole gave a laudable on-screen performance, Lawrence actually stood a mere 5 foot 5 inches in his cotton socks. This is why George VII was supplied with, and retains today, a smaller-diameter rear wheel.

A British Army colonel famous for his dashing desert exploits in the Middle East campaign of 1916-18, Lawrence abruptly resigned his commission, exasperated by the alacrity with which international statesmen reneged on earlier pledges to Arab leaders. His disgust with diplomats accelerated a return to the private world of academia, from within whose milder surroundings he wrote his classic Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Then the enigmatic man insisted upon joining the Royal Air Force as a common enlisted airman! Retiring from the RAF in early 1935 and, for once, not attracting any undue press attention, Lawrence was relishing withdrawal to Clouds Hill, his miniscule cottage at Bovington, where he wrote and passed time in genteel “rustication.”

Although anxious concerning future income, there was no intention of relinquishing his valued motorcycling. In fact, some 18 months before entering Civvy Street, he’d commissioned Mr. Brough to begin construction of a replacement SS100-to be known as George VIII-fitted with the latest-series J.A.P. engine. In anticipation of receiving this replacement machine, Lawrence removed George VII’s rear-mounted luggage panniers and its cherished stainless-steel fuel tank-crafted, like all Brough tanks, by the Skegness Sheet Metal Company. A factory black-painted “slave” item was loaned in the interim (and is still in place today).

By all accounts, the new machine was completed early in 1934, but in factory tests experienced “carburetion problems.” An inability “to run smoothly low down” persisted throughout that year, causing Lawrence at one point to consult with Mr. Binks (of Amal Carburettors Ltd.) himself. Philosophically, he insisted to George Brough that his next purchase be “better right, than rushed.” A collection date of May/June, 1935, had been tentatively agreed; tragically, events conspired to keep George VIII from its rightful owner.

Factory records show Brough sold this machine as new to its main agent in Cambridge, King & Harper.

Most likely, it was equipped with TEL’s favorite “rustfree” fuel tank! Postwar, this bike never surfaced. (Historical footnote: Britain entered WWII suffering a nationwide metal famine of all types. The government appealed for “any old iron.” Outhouses, garages and backyards were dutifully scoured. In present-day U.K. vintage circles, they ruminate still about earnest War Widows donating an absent bread-winner’s lovingly stored motorbike, or two, to the official scrapman, and feeling patriotic about the deed!)

After the crash, Lawrence’s brother consigned a not-thatbadly-damaged George VII to Nottingham for repair, whereafter it was sold to the same King & Harper dealership. Ownership passed on September 3, 1935, to Robert Stephen Monro, an opthalmic surgeon from Putney, London. But feeling constrained by the increase in suburban speed limits and marginally intimidated by the bike’s “decidedly sporty power curve,” Dr. Monro returned it to King & Harper within a twelvemonth and exchanged it for a flat-Twin BMW. In a strangely karmic sidenote, when aged about 7, George VII’s present owner-who wishes to remain anonymous-suffered a temporary sight disorder and for a time attended Monro’s surgery at Morfield’s Hospital, London, never imagining he’d one day acquire the unique machine his consultant had previously possessed! Years later, he enjoyed several conversations with the distinguished surgeon, by now retired. Dr. Monro retained a formidable recall of many of his former Brough’s idiosyncrasies.

Next purchaser (March, 1936) was an interestingly named South African, Capt. Johannes Sari Leon Pretorius. But during wartime and beyond, the trail goes sketchy.

Circa 1960, a Portsmouth, Hampshire, engineer, seeking a lusty, cheap V-Twin, unknowingly extracted the long-vanished machine from some piled automotive detritus in Southampton, which-in a coronary-inducing scenario-was

already destined for the scrapyard. Mechanically healthy and complete, the Brough had gained a complementary sidecar in absentia. England, remember, had been on its knees-transportationally, at least -thanks to the effect of strict postwar fuel rationing, and 30-year-old 1 -liter behemotha were not that widely sought. So, blissfully unaware of its provenance, our man snapped up George VII-wait for it-for the princely sum of £1.

That’s about 3 dollars U.S.! Unsurprisingly, the original documentation had vanished, but after submitting engine/frame number details to the Motor Taxation Authority came positive news that the bike’s first owner was a certain “Thomas Edward Shaw,” one of Lawrence’s aliases, and yes, his last stated address was listed as “Clouds Hill, Bovington, Dorset.” The machine’s significance began to dawn.

In the fall of 1963, The Motor Cycle magazine’s David Dixon was dispatched by his editor to appraise this extraordinary motorcycle on behalf of their 150,000 subscribers. George VII was, by now, back on two wheels in gentle local usage, and had made a well-publicized attendance at the annual London-to-Brighton Pioneer Run. Arriving at the rendezvous after a brisk spin down from the capital on a modem 650cc Triumph, Dixon not unnaturally reacted with mild disbelief as the Brough was warmed, commenting, “the Twin seemed from the horseless-carriage age.. .lots of mechanical clatter from exposed valvegear.. .a strange waffling burble from the exhaust. Where was the magnetism.. .the attraction. . .that lured discerning men in the 1930s?”

Dixon recently recalled, “It was very different. It was also the first B-S I’d ever straddled. But the farther I rode, the more it appealed.” Resulting from Dixon’s article were protestations in “Letters to the Editor,” primarily from cognoscenti anciens who’d overlooked his wordier impressions of galloping across Portsdown Hill where “...on a mere whiff of gas it settled into a loping 50-mph stride. I was wafted along on the breeze of yesteryear...the cotton wool punch of the power unit was something I had never known before.” Criticism from the Prewar Brigade had mistakenly concentrated on Dixon’s remarks during the initial warm-up. No, sir! Thirtysomething George VII did not betray its pedigree that October day.

It was in 1970s Britain when folk awoke to the aura attached to non-current machinery. No hard and fast rules, but whenever the artifacts in question were in reasonably original condition or unrestored, or were of large displacement, or had been owned/ridden/raced by persons prominent, suddenly said objets were valuable. Intrinsically so. Coincident to this newfound appreciation for hand-builts and general exotica, George VII changed hands again. But that transaction-nearly a quarter-century back-thankfully was not concluded in favor of the brightest wheeler-dealer on the block. From a raft of potential purchasers, the Brough was secured by our anonymous motorcycle enthusiast, whose love for Lawrence material pre-dated his craze for a few selected brands of motorcycle (currently, two further Broughs, a 1913 Precision, ohv and cammy Nortons, a perfect-specimen ’59 Bonnie and other délectables). “Definitely an expensive combination,” he grins ruefully. Questioned concerning George VII’s long-term prospects, especially in view of several speculative stories published in British broadsheets during 1998-99, the present owner sighs dismissively. This crucial question was visited anon. As an empathy with the owner evolved, it was painful observing how the stewardship of such a cherished mechanical icon can generate vicious public intrusion. Visitors appear unannounced; other approaches arrive via unsolicited mail and telephone-mainly opportunists and chancers, but some are legitimately interested in T.E. Lawrence, and in this particular SSI 00.

To my lighthearted query whether he might consider selling his “best” Brough, and with those proceeds acquire a boat, an aeroplane or a work of art, the owner answered thus: “The custody of George VII has provided tremendous pleasure over many years. At the end of the day, the pressure from time-wasters and speculators, which never stops, is very wearing. (But) wouldn’t it be a nightmare if George VII went to the wrong home?”

The long-silenced subject of all this attention rests meantime beneath generous sheeting in Dorset. The residence is barely 30 minutes from that straight, bumpy, undulating length of blacktop across Bovington Heath, where, 65 years ago-during the identical week these words were composed-a nicely loosened SSI00 innocently transformed itself into an important historical conduit.

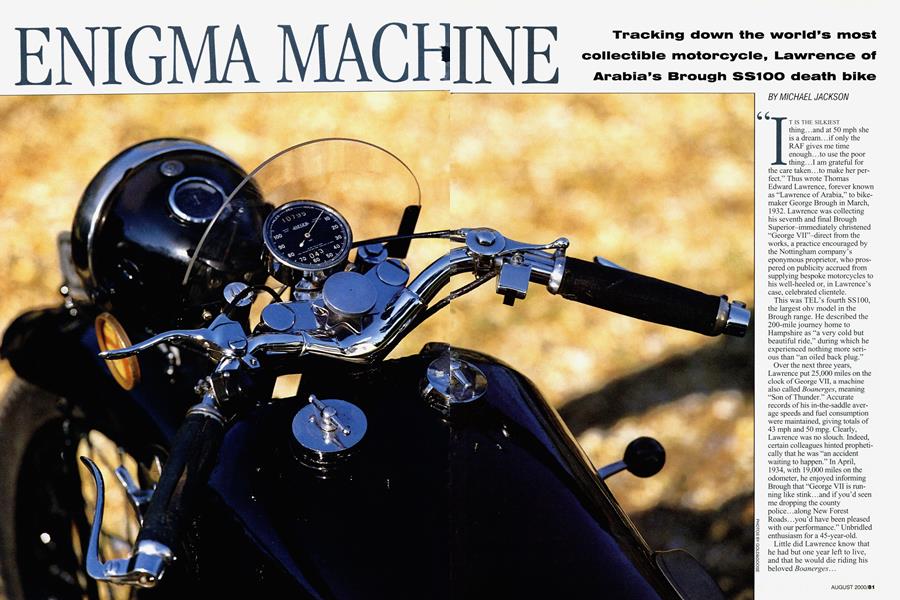

From months of research, I knew the machine’s particulars. Antithesising Henry Ford, it was rare for two flagshipmodel SSI00s, even when built side by side, to appear identical. Part of each bike’s raison d’être, if you like, was the Brough company’s skill in enabling its customers to select certain proprietary components of their choosing. George VII thus was handsomely customized at the time of supply by means of its smaller 19-inch rear wheel and that stainless-steel tank. There’s more but, logically, let’s start with the engine and chassis.

The bike employed Brough’s cantilever form of frictiondamped rear suspension, which the company pioneered, together with its own brand of “Castle” fork at front-which, as we now know, uncannily resemble the forks manufactured by a good ol’ American Colossus in downtown Milwaukee! Irrespective where designed, a Brough was a superbly sus-

pended machine in its time. The narrow-angle J.A.P. V-Twin was admired for its long-stroke characteristics, bore/stroke measuring 80 x 99mm. Displacing 995cc, this was the motor coveted by the competition fraternity for events at Brooklands Raceway, or for speed runs on the sand at Pembroke. George VII, per the majority of its ohv siblings, was fitted with a Pilgrim oil pump and Lucas electrics. The same Joseph Lucas? It must be stated, pronto, that Lucas components were at the time built up to a specification, not down to a price, as in postwar “Prince of Darkness” days! Lawrence’s “menu” also included an engine-sprocket shock absorber, a Lycett saddle with enclosed springs and a 120mph Jaeger speedometer. Proudly bearing registration number GW 2275, George VII left the factory, according to its Works Record Card, fitted with a quaintly described set of “Large Alpine Carriers and Bags with Valises.” A tad below Louis Vuitton, perhaps, as supplied to carrosserie-constructed automobiles in that era, but gentlemanly stuff all the same.

Last fired up for a TV station in the 1980s, and drained of fluids, it seemed-without feeling mawkish-that George VII slept under its tarp, possibly embalmed. Beneath its cover the somnolent machine stretched for yards. I checked. The distance between the vertical edges of front and rear tires measured 7 foot 6 inches. That’s one long motorcycle, yet, in silhouette it stood no higher than a modem.

But would the world’s most famous motorcycle disappoint? Finally, the sheet was pulled. If first impressions are memorable, here’s what I saw: The eye focussed on a vast spread of black paint broken here and there by patches of chromium-plated parts. And those dimensions? Long and low, for sure, and aside from the tank, narrow for a lOOOcc Twin good for 100-plus mph at one time. A fine patina, no rust, no corrosion. It may sound corny, but I believe I also detected a hint of menace within the deep “blackness” of its livery.

On the street, way back when, small boys would sidle up to sporting motorcyclists and ask, cheekily, “Wot’ 11 she do, mister?” Friendlier riders would reply, “Oh, about 80 per, downhill, with the wind behind...” The small boys returned to their conkers, content. In today’s sophisticated climate, the street-wise young

know every vehicle’s speed and value-they heard it on the Internet grapevine. Unless that tasty set o’ wheels momentarily holding their attention happens to be something mature. That throws ’em. Spotting George VII discreetly parked, one visualizes this cool exchange unfolding: “Hey man, cool, what’s that gotta be worth?”

On this occasion, there is a definitive retort. Owner puts arm around junior’s shoulder and whispers reverently, “Savor this moment, my lad. You’re looking at the world’s first seven-figure motorcycle...”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNed's Sled

August 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCharacter Infusion

August 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTwo Crankshafts?

August 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEurope Gets Naked!

August 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupIndian's Sporting Scout

August 2000 By Wendy F. Black