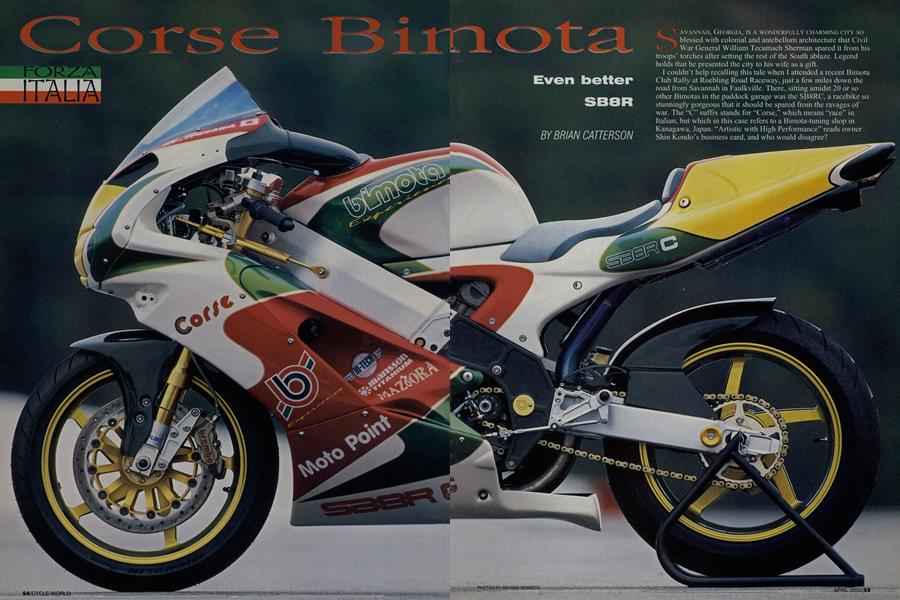

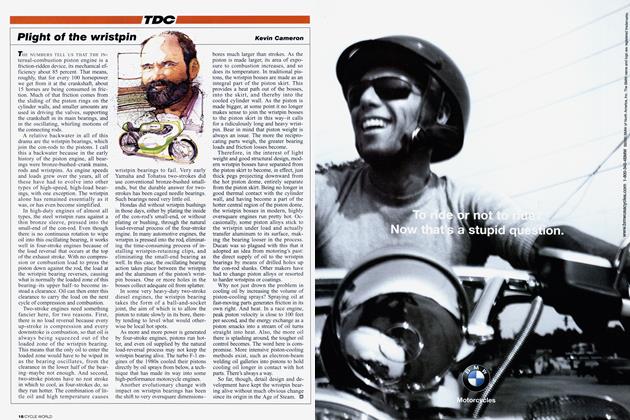

Corse Bimota

FORZA ITALIA

Even better SB8R

BRIAN CATTERSON

AVANNAH, GEORGIA, IS A WONDERFULLY CHARMING CITY so blessed with colonial and antebellum architecture that Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman spared it from his troops’ torches after setting the rest of the South ablaze. Legend holds that he presented the city to his wife as a gift.

I couldn’t help recalling this tale when I attended a recent Bimota Club Rally at Roebling Road Raceway, just a few miles down the road from Savannah in Faulkville. There, sitting amidst 20 or so other Bimotas in the paddock garage was the SB8RC, a racebike so stunningly gorgeous that it should be spared from the ravages of war. The “C” suffix stands for “Corse,” which means “race” in Italian, but which in this case refers to a Bimota-tuning shop in

Kanagawa, Japan. “Artistic with High Performance” reads owner Shin Rondo’s business card, and who would disagree?

Kondo is best known on these shores as the builder of the GSX-R1100-powered SB6R that went 202 mph at an Eastern Timing Association event in North Carolina a couple of years ago. Since then, he has been fettling one of the new TL1000Rpowered SB8Rs, and his handiwork shows. Bimota is universally revered for its intricate machine work that borders on fine art. The fact that Kondo improves upon this makes his talent that much more impressive. Titanium is Kondo’s favored medium, and indeed, the bike bristles with the stuff from

stem to stern Every single one of the approximately 300 fasteners has been replaced with Ti equivalents-even the bleeder nipples! If you've ever priced titanium hardware, you know buying that many pieces would cost more than some complete motorcycles.

It's the Ti exhaust that really gets your attention, though. Dubbed "Tunnel Port," the $4500 system begins with spig ots machined from titanium billet, then mates tapered header pipes with twin tailpipes that run up under the seat to siamese into a single outlet that fills the hole where the tail light used to be. Noting the absence of a rear subframe, you might be led to believe that the mufflers support the weight of the rider sitting in the saddle, but in fact the opposite is true; the carbon-fiber seat is load-bearing, and the mufflers hang from beneath it. Corse carbon-tube clip-ons give the rider something to hold onto while Japanese Hi-Tech aluminum rearsets give him someplace to put his feet.

Wherever possible, Kondo upgraded the bike’s components to Grand Prix/World Superbike-spec. The fork is an inverted 43mm Öhlins held by a Corse top triple-clamp; the shock is the stock Öhlins upgraded with an aluminum body and remote hydraulic preload adjuster; the steering damper is a goldanodized Öhlins; the brakes consist of Brembo “Monoblock” four-piston calipers grasping Corse’s own rotors; and the wheels are 17-inch Marchesini mags in 3.75-inch front and 6.0-inch rear widths. Ordinarily, the 391-pound machine wears Michelin slicks, but with intermittent sprinkles at our test, we opted for race-compound Pilots. Engine performance was improved not through radical internal modifications, but through better flow and breathing. A set of 12.5:1 Cosworth pistons works in conjunction with a Bimota Experience racing fuelinjection kit that positions a mixture-adjustment knob where the rider can reach it on the top triple-clamp. The engine puts power to the ground via a Suzuki race-kit closeratio gearbox and a set of Corse sprockets. Kondo says the bike makes 130 horsepower at the rear wheel, a very believable figure.

The SB8RC made a dream debut when rider Masanori Hanawa won the Battle of the Twins support race between legs of the World Superbike round at Sugo, Japan, last October. Now, Kondo is setting his sights on the AHRMA Sound of Thunder race at Daytona.

Which is where I come in. After posting respectable lap times and managing not to crash while testing a standard SB8R at Misano, Italy, last December, I’d been invited by Bob Smith of U.S. Bimota importer Moto Point to test the Corse bike with an eye toward racing it at Daytona. Given that the bike was a proven winner, however, I couldn’t help thinking that it wasn’t the bike that was being evaluated so much as me!

The weekend started off slowly with overcast skies, a damp track and a mandatory follow-the-leader session behind local racing-school instructor Frank Kinsey. But while the tortoise-paced laps helped reacquaint me with the racing line (I’d been to Roebling Road once before, for a Yamaha intro in 1994), they also drew my attention to the slippery-looking patches that dotted the circuit, legacy of a bad repaving job. This sort of thing weighs heavily on your conscious when you’re riding a one-off racebike valued somewhere in six figures-to say nothing of the fact that my Daytona ride hung in the balance.

I think former racer Joe Lamiroult said it best. After setting fast time on his own well-sorted SB8R the first day, he threw a leg over the Corse bike only to suffer performance anxiety. “I don’t know how you do it,” he told me afterward. “I think I was 10 seconds a lap slower than on my own bike.”

I can relate, brother. It wasn’t until after lunch on the second day that I finally stopped trying to “thread the needle” between the patches and started ignoring them. Between that and incessant chassis adjustments, my confidence shot up and lap times dropped down dramatically.

A standard SB8R is a splendid sportbike, with a broad spread of usable power and ultra-precise handling. To date, I’ve only seen the Bimota

included in one comparison test, conducted by Italy’s Motociclismo magazine, and it emerged victorious, bettering an Aprilia RSV Mille’s and Ducati 996’s lap times by a pube.

The Corse racebike works just like a standard SB8R, only better in every way. The increased power output and reduced weight predictably let the modified bike accelerate harder, corner faster and stop quicker than a stocker. While the broad powerband enabled me to hold third gear through all four corners behind the paddock, the closeratio gearbox and electronic speed-shifter let things happen in a real hurry down the front straight. The Stack digital dash display routinely indicated 170 mph at the entrance to Turn 1, a Hail Mary, decreasing-radius righthander through which you trail-brake, knee on the deck, all the way to the apex of Turn 2.

Early on, I was hindered by a vague feeling from the front end that made me reluctant to push it too hard. That situation was rectified for the last session of the weekend, however, when after making one last round of chassis adjustments and fitting a new rear tire I was rewarded with lap times nearly 3 seconds quicker than my previous best. But while on the outside I was hooked up and hauling, on the inside I was borderline terrified. Suddenly, it was as if the whole world had been switched into Fast Forward, everything coming at me so quickly I couldn’t focus my eyes. Having found the elusive front-end feedback, I was able to lean the bike over so far through long, fast, lefthand Turn 3 that I was experiencing vertigo! I’m certain that in time, my brain would have adjusted to the speed, but a lurid slide followed by a sudden snap as I crested the little rise exiting 120-mph-plus Turn 9 convinced me I was done for the day. I rolled back the throttle, gave a little wave to the guys behind the pit wall, then slowly cruised back to the paddock.

When I returned to the garage, Kondo was all smiles, which could only have meant one thing. Showing me the lap time displayed on his stopwatch, he said, “Tell me, what do we need to do to the bike for Daytona?”

“Just one thing,” I replied. “Change the numbers.” □