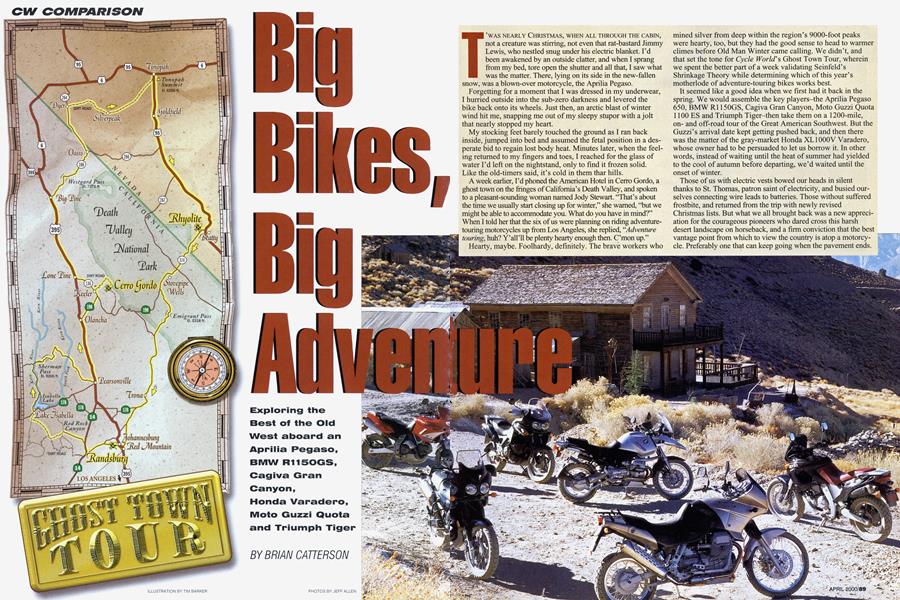

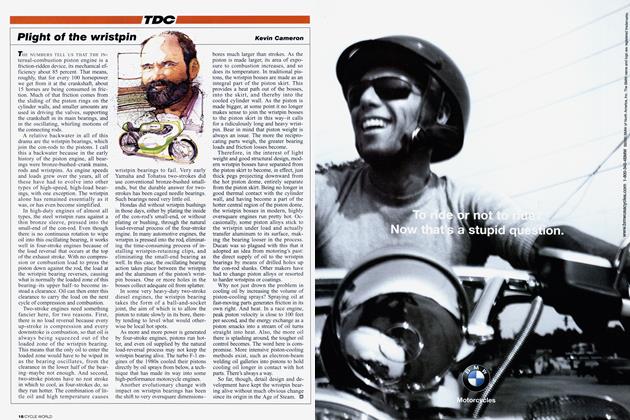

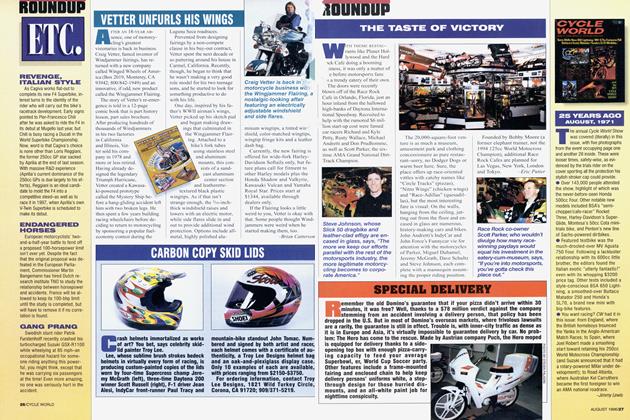

Big Bikes, Big Adventure

CW COMPARISON

GHOST TOWN TOUR

Exploring the Best of the Old West aboard an Aprilia Pegaso, BMW R1150GS, Cagiva Gran Canyon, Honda Varadero, Moto Guzzi Quota and Triumph Tiger

BRIAN CATTERSON

T’WAS NEARLY CHRISTMAS, WHEN ALL THROUGH THE CABIN, not a creature was stirring, not even that rat-bastard Jimmy Lewis, who nestled snug under his electric blanket. I’d been awakened by an outside clatter, and when I sprang from my bed, tore open the shutter and all that, I saw what was the matter. There, lying on its side in the new-fallen snow, was a blown-over motorcycle, the Aprilia Pegaso.

Forgetting for a moment that I was dressed in my underwear, I hurried outside into the sub-zero darkness and levered the bike back onto its wheels. Just then, an arctic blast of winter wind hit me, snapping me out of my sleepy stupor with a jolt that nearly stopped my heart.

My stocking feet barely touched the ground as I ran back inside, jumped into bed and assumed the fetal position in a desperate bid to regain lost body heat. Minutes later, when the feeling returned to my fingers and toes, I reached for the glass of water I’d left on the nightstand, only to find it frozen solid. Like the old-timers said, it’s cold in them thar hills.

A week earlier, I’d phoned the American Hotel in Cerro Gordo, a ghost town on the fringes of California’s Death Valley, and spoken to a pleasant-sounding woman named Jody Stewart. “That’s about the time we usually start closing up for winter,” she warned, “but we might be able to accommodate you. What do you have in mind?” When I told her that the six of us were planning on riding adventuretouring motorcycles up from Los Angeles, she replied, “Adventure touring, huh? Y’all’ll be plenty hearty enough then. C’mon up.” Hearty, maybe. Foolhardy, definitely. The brave workers who mined silver from deep within the region’s 9000-foot peaks were hearty, too, but they had the good sense to head to warmer climes before Old Man Winter came calling. We didn’t, and that set the tone for Cycle World's Ghost Town Tour, wherein we spent the better part of a week validating Seinfeld’s Shrinkage Theory while determining which of this year’s motherlode of adventure-touring bikes works best.

It seemed like a good idea when we first had it back in the spring. We would assemble the key players-the Aprilia Pegaso 650, BMW RI 150GS, Cagiva Gran Canyon, Moto Guzzi Quota 1100 ES and Triumph Tiger-then take them on a 1200-mile, onand off-road tour of the Great American Southwest. But the Guzzi’s arrival date kept getting pushed back, and then there was the matter of the gray-market Honda XL1000V Varadero, whose owner had to be persuaded to let us borrow it. In other words, instead of waiting until the heat of summer had yielded to the cool of autumn before departing, we’d waited until the onset of winter.

Those of us with electric vests bowed our heads in silent thanks to St. Thomas, patron saint of electricity, and busied ourselves connecting wire leads to batteries. Those without suffered frostbite, and returned from the trip with newly revised Christmas lists. But what we all brought back was a new appreciation for the courageous pioneers who dared cross this harsh desert landscape on horseback, and a firm conviction that the best vantage point from which to view the country is atop a motorcycle. Preferably one that can keep going when the pavement ends.

Aprilia Pegaso 650 In the land of giants

In motorcycling, as in sex, size matters. The key is scale: If you surround yourself with blokes with little, er, units, well then, yours is big. And vice versa.

Such is the case with the Aprilia Pegaso 650. Viewed alongside a traditional dual-purpose bike, it’s massive, its capacious fairing, fuel tank and seat apparently deriving from some sort of two-wheeled Winnebago. Viewed alongside any of the other adventure-touring bikes in this group, however, it’s tiny, an S.S. Minnow in a sea of Titanics.

But don’t take our word for it, trust in Mother Nature, who blew over the 411-pound Pegaso not once, but two nights in a row. She huffed and she puffed, but she failed to blow any of the other bikes down.

The Aprilia’s light weight made it the most desirable mount when the road turned to dirt, and second only to the Cagiva when the going got twisty. Its suspension, while sprung too softly for hard-core off-road use, is nicely balanced and well-damped, and its comparatively light, neutral steering makes it a cinch to toss back and forth through essbends. The front brake is strong but not grabby, while the rear, which we previously reported overheated and faded (CW, February), made liars out of us during this trip, thanks in large part to the cold.

Like most of the bikes in this test, the Pegaso features a mixed bag of dirt amenities. While it has handguards, a plastic skidplate and excellent Pirelli MT80 tires, it also has slippery-when-wet rubber footpegs and non-folding foot controls. We were barely a mile into our first off-road excursion when the shift lever got pretzeled by a rock. Other casualties of war included an errant exhaust heat shield and no fewer than four flat rear tires.

The most commonly voiced complaint about the Pegaso, though, concerned its engine, a Rotax-built, five-valve Single whose 37 horsepower pales in comparison to the much more powerful Twins and Triple in this group. This was painfully evident while climbing 7000-foot Westgard Pass, where I suffered the indignity of having to follow Off-Road Editor Lewis and the Cagiva up a paved twisting mountain road. Once we crested the summit, however, revenge was mine!

APRILIA

PEGASO 650

$7877

▲Ups

A Fast compared to most Singles A Tool-less air-filter access A Best dirtbike of the bunch

Downs

▼ Slow compared to most Twins ▼ Requires oxygen at altitude ▼ Could be upstaged by the new BMW F650GS

The fact that the Pegaso is “only” a 652cc Single prompted OF Marketing Director Corey Eastman to voice his opinion that the bike perhaps didn’t belong in this comparison, that it was somehow ill-suited to adventure touring. Jimmy, meanwhile, wondered why anyone would choose it over a Suzuki DR650E, which is more dirt-worthy and much less expensive.

The pair’s skepticism was invalidated at a gas station in Lone Pine, California, where we encountered a fellow motorcyclist on his way to Death Valley. His ride? A loaded-for-bear BMW F650 Funduro, a machine that is all but identical to the Pegaso, and which the Italians in fact produce for the Germans. Call it an unsolicited testimonial.

BMW B1150GS Built like a Panzer

“Where’d you go?!” an excited Corey asked me as we stopped at the end of a powerline road on our way to Rhyolite,

Nevada. “I saw this huge cloud of dust, and thought you’d gone down, but when I got there, you were gone!”

You hear these sorts of comments a lot when you’re riding the BMW RI 150GS.

The reason is simple: The Beemer doesn’t go over obstacles, it goes through them!

Although at 549 pounds the GS is the heaviest machine here by a couple of

pounds, it doesn’t feel that way. The 1130cc, horizontally opposed, twin-cylinder engine imparts the bike with a low center of gravity, while acting as a stressed member in the solid-handling chassis. Lending a hand in the latter regard is BMW’s proprietary Telelever front suspension, the A-arm of which transfers forces that would bind conventional telescopic forks directly into the engine case. The result is a plush, stiction-free ride that feels normal except for the fact that the front end doesn’t dive under braking.

At first, the Paralever rear suspension bottomed too easily over square-edged bumps, resulting in the aforementioned clouds of dust, but dialing in some more shock-spring preload with the handy adjuster knob rectified that.

Dropping tire pressures to 25 psi also helped the handling, greatly improving traction in sand. Before that, it was a swap meet on wheels.

While you wouldn’t call the Boxer’s engine exciting, it does work well. Crisp fuel injection, coupled with prodigious torque (68 peak foot-pounds at 5500 rpm), gives it an electric-motor quality. The new six-speed transmission has perfectly spaced ratios, with the top “E” gear (for Economy) letting the motor lope effortlessly at freeway speeds. This goes a long way toward diminishing the “Boxer buzz” caused by the rocking-couple action of the opposed conrods working in separate planes.

BMW

R1150GS

$14,190

Ups

A Floats like a butterfly A Best toolkit you'll never need A Heated handgrips rule! A Loaf-along sixth gear

Downs

Buzzes like a bee Good thing it’s a do-it-all bike, you couldn’t afford another!

But while the gear spacing is good, the gearshift action could be better. First engages with a vagueness contradicted only by the changing gear-indicator LCD on the dash, and every other shift produces an audible “clunk.” Clutch action also could be improved; it works like a light switch, on or off, with no dimmer.

Where the GS shines is in the details. BMW has been refining the adventure-touring concept since inventing it 20 years ago, and it shows. Dirt-oriented features such as sturdy

handguards, a metal skidplate and knurled brake pedal and footpegs are balanced by comfort amenities such as an adjustable windscreen, heated handgrips,

adjustableheight seat and an accessory outlet for an electric vest or what

have you. There’s shaft drive, a centerstand (remember those?), mounts for the optional saddlebags, an auxiliary

luggage rack beneath the removable passenger seat, a steering lock that works with the bars turned either way and a giant thumbwheel that lets you reset the tripmeter even while wearing winter gloves. Standard safety features include hazard lights and an anti-lock braking system that can be disabled for off-road use-not that it needs to be. And there’s a toolkit that would do a home workshop proud, complete with compressed-air cartridges and flat-repair plugs for the tubeless Metzeier Tourance tires. With all these features, is it any wonder the GS is heavy?

We only had two minor problems with the Boxer during our trip. The right-side sparkplug-wire cover went missing, probably when I kicked it while paddling through sand in Red Rock Canyon. And the left-side saddlebag mount broke after Jimmy’s 10-pound toolpack bounced up and down inside. Considering the abuse the bikes were subjected to, an excellent report card.

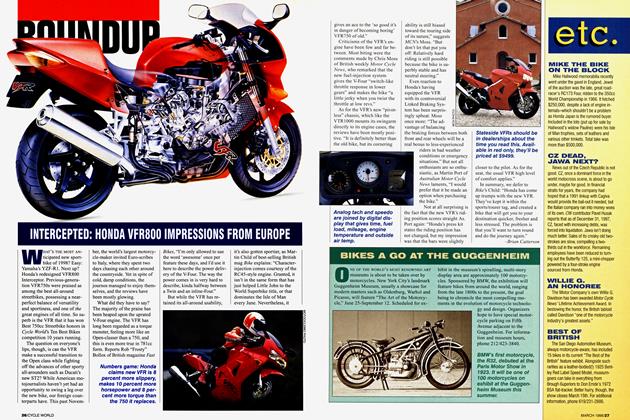

Cagiva Gran Canyon Sportbike in dirt duds

Electric vest or no, when it’s 19 degrees in Tonopah, Nevada, and you’re going 75 mph on a bike with next-to-no windscreen, you don’t care how great a bike looks or how well it works on a twisty backroad. All you care about is trading for something with a big fairing and handguards. And heated grips, if possible.

As nice a motorcycle as we all agreed the Cagiva Gran Canyon is, it was hard to get past the fact that it needed a taller windscreen for this trip. Fortunately, one is available as an option, and in fact will come standard on year-2000 models. But realizing that such a thing exists and we didn’t have one only made us more miserable.

Regular readers already know that we like the Gran Canyon. We raved about it in our initial test (CW, February, 1999), gave it an Honorable Mention in our annual Ten Best Bikes balloting, and somehow neglected to return Cagiva’s phone calls when we thought they might want it back. One year and 6000 miles later, it’s still going strong.

The original tires were, however, wom-out, and replacing them with an identical set proved impossible. The standard Pirelli MT80s had been superseded by the new MT90s, and unfortunately, there were no such fronts in the U.S. In a pinch, we substituted an MT60, basically a roadrace rain tire that comes standard on many supermotard models. The addition of the sticky, heavily grooved front tire gave the Cagiva even more of a handling advantage on the street, and unparalleled traction in the dirt.

The Gran Canyon offers the most compelling argument yet that adventure-touring bikes are better-suited to real-world riding than anything else. It’s a sad irony that as motorcycles get faster, roads get worse. Long-travel suspension turns back the hands of time. Suddenly, roads are smooth again, or at least less bumpy.

But while the Gran Canyon’s stellar handling rivals that of a sportbike, its most compelling feature is its engine-a fuel-injected, 904cc, desmo Ducati V-Twin that pumps out 60 eminently usable horsepower. Jimmy commented that this was the only motor in the group with any “snap,” and everyone agreed.

Aside from the aforementioned concerns about wind protection, the only place the Gran Canyon came up short was in the dirt. The low handlebar and flared fuel tank prevent you from standing up, and the heavily damped suspension that works so well on twisty backroads

CAGIVA

GRAN CANYON

$8995

Ups

A Soulful Ducati V-Twin engine A Snazzy, two-wheeled-Ferrari looks A Best sportbike of the bunch

Downs

▼ Cold air coming over the windscreen ▼ Overdamped for the dirt ▼ Limited fuel range

conspires against you on dirt washboard. As Sports Editor Mark Hoyer noted after riding it up Cerro Gordo’s winding, 9-mile-long dirt road at night, “Suspension sent ‘packing,’ and somebody set me on fire please!”

The Cagiva also lacks range for cross-country excursions. Its 5.3-gallon fuel capacity, combined with its thirsty motor, makes it good for 160 miles max. As a result, it was the only bike to run out of gas during our trip.

Those who spend their Sunday mornings racing to breakfast would do well to consider the Gran Canyon (300 of which will be imported this year), or its forthcoming (in 2001) successor, the Suzuki TLlOOOS-powered Navigator. But for our purposes here, the Gran Canyon misses the mark. We can’t help wondering what happened to the previous-generation Elefant 900, which was more faithful to this genre’s Paris-to-Dakar heritage. Bring back that bike with the Gran Canyon’s fuel injection and it would be a real contender.

Honda XL1000V Varadero Land yacht

“Ohmygod,” said Jimmy when he first spied the Honda XL1000V Varadero. “We’re going to ride that thing in the dirt?” This from a guy who races a BMW Twin in the Dakar Rally.

Frankly, we didn’t know what to expect from the Varadero, a foreign-market model that sells for around $12,000 in Europe, but which American Honda has no plans to import. All we knew was what we’d read in Spain’s Motociclismo magazine, whose riding impression we reprinted in our May, 1999, issue. In a nutshell, what the report said was that the Varadero was a very large motorcycle better suited to touring than adventure-touring. As proved to be the case.

Though the name is said to derive from a Cuban resort town, varadero means “shipyard” in Spanish, as in the place where fishermen beach their boats at night. Given the bike’s immense size, you can imagine the discussion that led to its name.

“This thing’s a boat.” “A boat? It’s the whole damn shipyard!” “Hey, how do you say that in Spanish?”

The Varadero’s touring intent is apparent in its Gold Wing-sized fairing, bulbous 6.5-gallon fuel tank and threespoke mag wheels, the only bike in this test so equipped. Its spacious seat defines cush, even if a certain pizza-and-beerchallenged staffer said it made his tailbone ache.

But while everyone who rode the Varadero in the dirt admitted to being intimidated-someone christened it the “Very Daring,” and the nickname stuck-the general consensus was that it works far better than expected. At anything above a brisk walking pace, the bike’s top-heavy feeling largely disappears, and its mass seems to melt away. Not even the linked brakes misbehave; as was the case with the BMW’s ABS, we were pleasantly surprised by how well the system performs in the dirt.

Lurking beneath the Varadero’s voluminous plastic is a VTR 1000 Superhawk-derived V-Twin, which Assistant Art Director Brad Zerbel found hard to believe. “What happened to the motor?” he asked, aghast. “This thing feels bound and gagged.”

In a sense, he was right. The Superhawk’s engine was retuned for use in the Varadero, with smaller 42mm (as opposed to 48mm) carburetors and a heavier flywheel to boost lowend power. Which it does, as evidenced by the XL-V’s use of a fivespeed gearbox, one less cog than in the VTR. Yet even in “neutered” form, the Honda was the quickest, fastest and most powerful bike in this test. Its sub-12-second quarter-mile time,

HONDA

XL1000V VARADERO

Air>s

A Typical Honda refinement A Fairing big enough to live behind A Best touring bike here

Downs

▼ Typical Honda refinement ▼ Wide between the knees ▼ Good thing it’s got a big gas tank, it drinks like a fish! ▼ Not coming soon to a Honda dealer near you

over-120-mph top speed and 80horsepower dyno reading stand head and shoulders above the rest. It just doesn’t feel that fast.

Though the Varadero’s aluminum swingarm pivots in its engine cases like the Superhawk’s, its box-section steel frame has nothing in common with the VTR’s aluminum-trellis job. Handling is generally good, with the exception of very un-Hondalike heavy steering that we light-

ened up by dialing in more shock-spring preload with the BMW-style adjuster knob.

These days, saying that a bike is a “typical Honda” is a backhanded compliment. Big Red’s engineers often refine their designs to the point that the bikes are so flawless, they’re boring. And while that’s true to an extent of the Varadero, it has one “typical Honda” feature that we wouldn’t have traded for anything on this trip: reliability. When all was said and done, the Varadero was the only bike that didn’t give us a single problem.

Of course, the Varadero won’t be giving you any problems either, because you can’t buy one. Unless you can convince American Honda that you-and a couple thousand of your closest friends-can’t live without one.

Moto Guzzi Quota 1100 ES Mulo Meccanico

I don’t believe in coincidences, which is why I stopped to pick up a seemingly insignificant screw I spied lying in the road while riding the Moto Guzzi Quota back and forth for Jeff Allen’s camera. I handed the fastener to Brad, who spent the next couple of minutes walking around the bikes looking for an empty hole. Failing to find one, he stuck the screw in his jacket pocket and forgot about it.

Until the next day. I was following Jimmy and the Guzzi on a dirt road near Lake Isabella, when I swerved to avoid a round black object lying in the trail. Like I said, I don’t believe in coincidences, so I started thinking about what the part might be...

Gadzooks! The Guzzi’s ignition cover! I sped up, caught Lewis (no mean feat-ask Heinz Kinigadner) and flagged him down. By the time I’d turned around and gone back to fetch the cover, Brad had stopped to pick it up. “Now I know where the screw goes,” he chuckled.

We reinstalled the cover with some bolts from Jimmy’s fanny pack, then resumed riding. Mere minutes later, however, we were forced to stop again when the Guzzi got a flat rear tire-the first of two such occurrences. Thank goodness it has a centerstand, one of only two in this group. But where the hell is the toolkit?!

Quota means “level” in Italian, as in an airplane’s cruising altitude. One learns such trivia by watching the TV screen between movies on international flights. But a more fitting name would have been Mulo Meccanico, in homage to the oddball three-wheeled flatbed that Guzzi built a half-century ago. The name fits for a number of reasons, not least the fact that the Quota is as stubborn as a mule. With a locomotivelike 63.2-inch wheelbase, it flat refuses to turn, preferring to go straight, which it does well even without tracks. The tall gearing, finicky clutch and clunky, long-throw gearchange conspire to further its obstinacy.

Sit in the saddle and you can’t help but notice how long a reach it is to the bars, exaggerated by the width of the bars themselves-34 inches, or a couple of inches wider than those on most dirtbikes. You also notice that there’s a significant amount of cold air coming over the fairing. The culprit here isn’t the fairing itself, it’s the distance between the fairing and your torso. Oh well, at least the tank is nice and slim, and the dirtbike-style seat is excellent. If it’s true that KTM-notorius for hard saddles-is buying Moto Guzzi, the Quota’s seat should be the first collaboration.

Like all current Guzzis, the Quota is powered by the company’s venerable longitudinal pushrod 1064cc VTwin. It’s a tractor of a motor, seemingly producing the same power at idle as at redline. Vibration is omnipresent, except when you close the throttle, when everything suddenly gets eerily smooth, the massive flywheels keeping the engine spinning indefinitely. Downshift, though, and there’s plenty of engine braking to be had, due to the large gaps between gear ratios. The Quota really would

MOTO GUZZI

QUOTA 1100 ES

$9995

Ups

A Attention-grabbing horn A Classy carbon-trimmed dash A Best seat of the bunch

Downs

▼ Anybody bring tools? ▼ Sui-sidestand ▼ Shaft effect only good for peering over car tops

work better with the six-speed transmission from the forthcoming V11 Sport.

What it needs most of all, however, is a torque-canceling linkage similar to that incorporated in the rear suspension of the now-discontinued Daytona. There’s a reason BMW went to the trouble of developing Paralever, and the Guzzi reminds you why. Whack open the throttle and the rear end rises, back off and it squats, both actions exacerbated by the Quota’s long-travel suspension. Considering that the rear suspension utilizes a quality Sachs-Boge shock, it ought to work well. But it doesn’t. Perhaps the engineers attempted to downplay the shaft-drive effect by dialing in a bunch of damping?

What the Guzzi is, is a half-hearted attempt to tap into Europe’s healthy appetite for adventure-touring bikes. But in spite of its many faults, it may find a receptive audience among retro-grouches and old-school BMW GS fans turned off by the new, high-tech Wunderboxers. Success by default? Perhaps. But success nonethless.

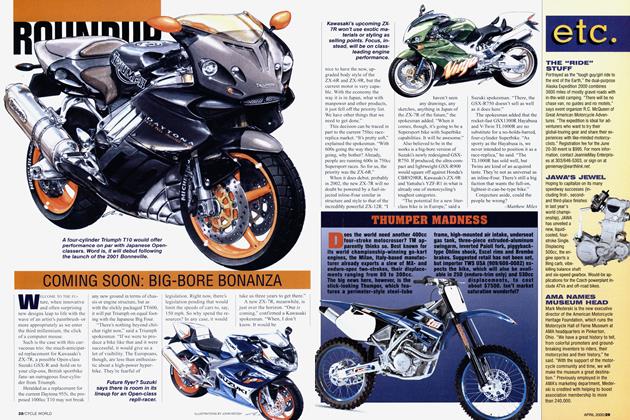

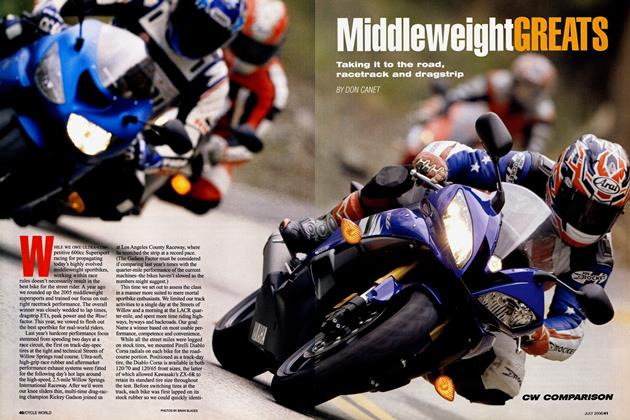

Triumph Tiger Range Rover syndrome

“Just like a Britbike,” I thought to myself as I watched a puddle of oil form under the Triumph Tiger. Only thing was, it was coming out of the top of the engine! Oh well, I guess that’s what happens when you drop a running motorcycle on ice and oil pumps out the crankcase breather into the airbox as you struggle to reach the killswitch.

The story got better with the retelling. It seems Mr. Hoyer and the Cagiva were proceeding cautiously across a sheet of ice up on Sherman Pass when he decided to stop and regroup at a dry spot. Which is okay; he has that right. But Mr. Eastman was following close behind on the Triumph, and suddenly confronted with a stopped motorcycle in his path, squeezed the front brake lever. The result was predictable, and while the bike trailed smoke for the remainder of the trip, there was no lasting damage.

The Tiger is the most distinctly different bike in this group. Its inline-three-cylinder engine essentially combines the 885cc displacement of first-generation T300 Triumphs with the fuel injection and shrink-wrapped cases of second-generation T500 models. Feeling like a cross between a Twin and a Four, the Triple produces a snarky growl at low revs, builds through a throaty-sounding midrange and climaxes in a banshee wail. It’s an intoxicating musical score that you want to hear over and over again. And which sounds even better with a set of pipes, never mind what the critters in the woods might think.

The Tiger’s peak power is down a bit from its racier stablemates (zoo-mates?), thanks to its bottom-end bias, but it still ranks near the top of this class in terms of outright performance. Unlike some earlier fuel-injected Triumphs, the Tiger has excellent throttle response, and a flat torque curve with no dips anywhere. Its clutch has a nice, light pull and smooth engagement, and its six-speed gearbox shifts well, too.

Much like the Cagiva, the Triumph feels like a longlegged sportbike. The seat is sculpted and low, so that you sit down inside the bike rather than on top of it; the wide fuel tank locks your knees in place; and while the handlebars have a motocross-style crossbar, they’re bent down at a funny angle, like a set of Superbike bars. Even the fairing is suggestive of a sportbike, as though a tall windscreen was tacked on top as an afterthought. The odd styling, combined with the swoosh graphics, made a few testers long for the masculine look of the previousgeneration Tiger.

Regardless, the Triumph works extremely well on the street, carving up twisties like the Grinch does roast beast. But it doesn’t fare as well in the dirt, where its performance is hindered by an overwhelming top-heavy feel-

TRIUMPH

TIGER

$10,499

Ups

A BMWs aren’t the only bikes with electric-vest outlets anymore A Or adjustable seats A Intoxicating exhaust note A Best fuel mileage of the bunch

Downs

▼ High center of gravity ▼ Sportbike seating position ▼ Vulnerable oil cooler

ing. Initially, the sacked-out rear suspension drew criticism for being harsh and bottoming easily, but in fairness, we’d been neglecting to adjust it while focusing on more urgent matters, such as the aforementioned flat tires, jettisoned parts, oil leaks, etc. When we finally got around to dialing-in some shockspring preload with the clever underseat adjuster, we were rewarded with a plush-yet-solid ride that rivaled the BMW’s. Pity we hadn’t done it sooner.

In the end, the general consensus was that the Triumph, like the Guzzi, is more styling exercise than engineering feat. While it has some nice adventure-touring features such as handguards, an adjustable-height seat and an electric-vest outlet, it’s really just a sportbike in drag.

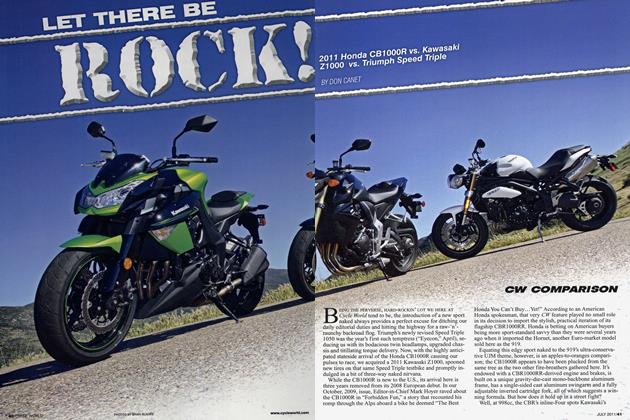

Conclusion

Any of these adventure-tourers could make you a happy camper. It just depends on what you like in a bike, and how you plan to use it. But if you want a true do-it-all motorcycle, the BMW RI 150GS should be your only choice. It isn’t the best in any particular category, but it does everything well and nothing poorly. True, it’s expensive, costing on average 50 percent more than the others. But as the old truism goes, you get more for your money-including, in this case, heated handgrips. On a trip like ours, that feature alone might be enough to clinch the deal. □