CYCLE WORLD TEST

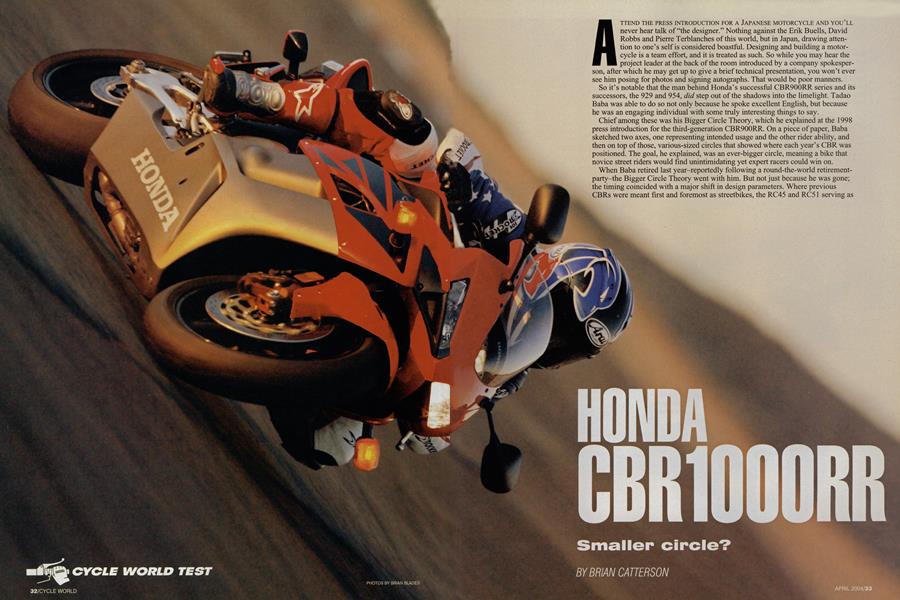

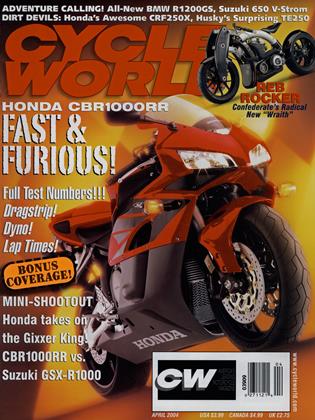

HONDA CBR1000RR

Smaller circle?

BRIAN CATTERSON

ATTEND THE PRESS INTRODUCTION FOR A JAPANESE MOTORCYCLE AND YOU'LL never hear talk of "the designer." Nothing against the Erik Buells, David Robbs and Pierre Terblanches of this world, but in Japan, drawing attention to one's self is considered boastful. Designing and building a motorcycle is a team effort, and it is treated as such. So while you may hear the project leader at the back of the room introduced by a company spokesperson, after which he may get up to give a brief technical presentation, you won't ever see him posing for photos and signing autographs. That would be poor manners.

So it’s notable that the man behind Honda’s successful CBR900RR series and its successors, the 929 and 954, did step out of the shadows into the limelight. Tadao Baba was able to do so not only because he spoke excellent English, but because he was an engaging individual with some truly interesting things to say.

Chief among these was his Bigger Circle Theory, which he explained at the 1998 press introduction for the third-generation CBR900RR. On a piece of paper, Baba sketched two axes, one representing intended usage and the other rider ability, and then on top of those, various-sized circles that showed where each year’s CBR was positioned. The goal, he explained, was an ever-bigger circle, meaning a bike that novice street riders would find unintimidating yet expert racers could win on.

When Baba retired last year-reportedly following a round-the-world retirementparty-the Bigger Circle Theory went with him. But not just because he was gone; the timing coincided with a major shift in design parameters. Where previous CBRs were meant first and foremost as streetbikes, the RC45 and RC51 serving as the basis for Honda’s racing Superbikes, this year the CBR1000RR will fill that role. Predictably, its circle would get smaller.

And so it’s no surprise to learn that the new project leader, Kunitaki Hara, drew from lessons learned in the making of the RC21IV MotoGP bike successfully ridden to back-toback world titles by Italian Valentino Rossi.

No surprise, either, that the CBR1000RR is a clean-sheet design, sharing not one single part with its predecessors. Yet in spite of this fact, it’s relatively conservative, eschewing radical innovation in favor of optimizing current practices.

As with all recent Honda sportbikes, the RR adheres to the principals of mass centralization, and so its major components are packaged as tightly as possible near the roll center. To this end, the inline four-cylinder engine was completely redesigned, its modestly oversquare cylinder dimensions making it extremely narrow for maximum cornering clearance, and its cylinder block inclined only slightly to move the engine as far forward as possible while leaving room for a massive curved radiator. A magnesium valve cover and oil pan help save weight.

The transmission also was redrawn, its vertically stacked main and countershafts forming what Honda calls a “triangulated” configuration with the crankshaft-can’t call it what the other guys call it, after all. The close-ratio, sixspeed gearbox is cassette-type, incidentally, which means racers can easily alter internal gear ratios-simply unbolt the right-side crankcase cover and the clutch, shift forks and drum come out as one assembly.

Lastly, moving the oil filter from the front the engine to the right side allowed the “center up” exhaust to tuck tightly against the front of the crankcase before sweeping under and up the underseat muffler.

The engine redesign laid the groundwork for the all-new aluminum chassis, which like the RC21 lV’s is equipped with a lengthy swingarm that is meant to aid traction exiting corners. Compared to last year’s CBR954RR, the 1000’s swingarm is 1.3 inches longer, yet its wheelbase grew just .6 of an inch. An all-new Unit Pro-Link rear suspension system does away with the traditional top shock mount on the frame, freeing up room for the gas tank to be positioned lower in the chassis for a lower center of gravity; a faux fuel tank cover lends the bike a conventional appearance. The relocated tank in turn lets the rider sit closer to the steering head for maximum front-end weight bias. Further aiding mass centralization, the few components that remain at the motorcycle’s periphery-the headlight, instruments and rear brake caliper, for example-were made as lightweight as possible.

Where the RR is somewhat innovative is in its electronics. A palm-sized 32-bit electronic control unit (ECU) features dual 3-D fuelinjection maps for each cylinder, and also oversees the ignition, emissions, two-stage ram-air, exhaust powervalve and the new Honda Electronic Steering Damper (HESD). Developed in conjunction with Kayaba, the damper mounts atop the steering stem, and drawing on feedback from the throttle-position and wheel-speed sensors uses a solenoidactuated valve to increase damping force commensurate with acceleration and road speed. The result is light, resistance-free steering at slow speeds and enhanced stability at higher speeds.

Of course, none of this would matter if the bike it was attached to was a stone, and the CBRIOOORR is anything but that. Strapped to the CW dyno, it pumped out 145 horsepower and 76 foot-pounds of torque, a significant increase from the 137 bhp and 72 ft.-lbs. recorded by the last CBR954RR we tested.

But while the 1000’s power output is up, so too is its “tonnage.” It weighs 431 pounds without gas or tools, some 25 lbs. more than the 954.

Not that you’ll ever notice that, mind you, because as with its slightly portly little brother, the CBR600RR, you’re struck by how small and light it feels. And how racy: With clip-on handlebars 1.8 inches lower than the 954’s, and footpegs higher and more rearset, the 1000 is notably more “purposeful.” Push the starter button (no choke required) and the engine jumps to life, settling into an idle that sounds raspier and much more menacing than previous Hondas. Blip the throttle and the revs zing upward with a shriek-not much flywheel here. Pull in the hydraulically actuated clutch lever, snick the tranny into first, dial on some throttle and let out the clutch, and the RR eases smoothly away. Get greedy with the throttle, however, and the clutch protests with a graunching sound that you won’t want to hear repeated.

The grabby clutch impeded our dragstrip testing somewhat, but with the bike’s forward weight bias and long swingarm doing their parts to quell wheelies, it still posted a respectable time of 10.14 seconds at 140.79 mph-a quarter-second quicker and 5 mph faster than the 954. Top speed also was up, the RR’s 178-mph showing easily besting the 954’s 167 mph.

Cruising on the street, you can’t help noticing how thin the seat padding feels under your butt, even if the Showa suspension impresses you with its bump compliance. You also notice how much weight you’re carrying in your wrists, though speeding up helps alleviate this concern as the wind smoothly flowing over the top of the screen helps prop up your body. Your attention then turns to engine vibration, which you feel though the bars (though not the pegs) in spite of there being a counterbalancer. That said, it’s more of a coarse buzz than a high-frequency tingle, so it’s unlikely to put your hands to sleep.

While we’re talking street riding here, we should point out that our test CBR1000RR averaged 37 mpg, which works out to a 178-mile range, far better than the RC51 that preceded it as Honda’s flagship Superbike. Speaking of the RC51, we’re glad to see that bike’s hard-to-read LCD tachometer didn’t make the jump; the RR has a nicely laid-out analog unit, complemented by a bright-white shift light that can be programmed to illuminate at any rpm from 5000 to 11,600 rpm, the latter figure just 500 revs shy of redline.

Exit the freeway, head into the hills and your comfort concerns disappear. Here, you’re more aware of the Double-R’s engine performance, which impresses you not just for the quantity of its horsepower, but for its quality-nothing this potent is so linear. And of its handling, which is flawless-with one caveat.

There are plenty of clichés to describe how solid the RR’s chassis feels, yet none of them do it justice; it really does feel like it’s “of a piece.” Swerve from side to side, as you would when scrubbing in a new set of tires, and there is no perception of chassis flex. Snap the bike over hard into a bend at high speed, and it does exactly what you tell it to. But lean it over partway, with the brakes on, into a downhill, off-camber, dust-strewn comer and...well, something’s clearly amiss.

We first became aware of this when we took our RR to a track day at the Streets of Willow Springs. Relatively tight, slow and bumpy, the Streets is unique among racetracks in that it has virtually no heavy braking zones; every comer requires a measure of trail-braking, and there’s a series of esses that are taken at partial throttle, emphasizing front-end feel. And here, the RR felt awful, falling into comers and worrying us that the front tire was going to slip away at any moment. We tried adjusting the suspension-an easy task, thanks to unimpeded access to the clickers and the shock-spring preload ramp-but nothing helped.

Road Test Editor Don Canet was particularly perplexed, because he’d raved about the Honda’s handling after attending the press introduction at Arizona Motorsports Park. The difference was there the bikes were shod with Bridgestone’s new BT-014 Battlax radiais, whereas our testbike was fitted with Pirelli Diablo Corsa radiais, the other planned OE fitment. We’ve tried the Diablos on other bikes and been impressed, so there’s nothing really wrong with them, but the front tire’s V-shaped profile didn’t seem to work with the RR’s steering geometry. Granted, this tendency may have been exacerbated by the fact that we ran slightly lower tire pressures (31 psi front, 29 rear) at the racetrack, but considering that it remained even after we reverted to street pressures (34 front, 36 rear), that wasn’t the issue.

Curious if tires would make a difference, we placed a call to Jon Seidel at American Honda, who arranged to meet us with a set of Bridgestones at the Streets a few days later. And no sooner did we change tires than the handling was cured. Suddenly, the RR steered like it should, nice and neutral, if maybe a tad heavier than some other sportbikes-though we’ll take that if it enhances stability. Front-end feel was improved to the point that we could confidently trail-brake into comers and exploit the Tokico radial-mounted fourpiston front brakes. Honda has long used Nissin as a brake supplier, but the change appears warranted as the Tokicos provide exceptional stopping power and feel. We also appreciated the virtually limitless cornering clearance allowed by the underseat muffler (we’d say “Ducati-style” underseat muffler, but we’d get a bunch of letters about how the Honda NR750 had one first, so we’ll leave that alone); only the footpeg feelers touched down.

With the front end sorted out, the rear end also came around-literally in places, as the combination of the engine’s linear power delivery and the chassis’ extended swingarm resulted in long, tire-hazing comer exits. If the RC211V is remotely this controllable, it’s no wonder Rossi made winning look so easy.

The CBRIOOORR may have a new mission in life, but the qualities that made its predecessors so endearing remain intact. Baba-san would be proud.

EDITORS' NOTES

TALK ABOUT HITTING THE APEX... NO, I don’t mean stringing together the perfect line around a favorite racetrack, I’m talking about hitting your apex. When a bike works as well as the Honda CBR1000RR does, that’s all you’re left to think about. Dyno charts, lap times, quarter-mile E.T.s, WHATEVER...Û\Q performance parameters of today’s 1000s are set only by our own fears.

If you get a Double-R, do yourself a favor and don’t go messin’ it up by tryin’ to fix it up. Leave it stock, go do some track days and ride it like it’s meant to be ridden. That’s the only way you’ll get to sample everything this engineeredfor-racing bike has to offer. Even if you failed Geometry, you’ll appreciate it at work here when all you’re thinking about is hitting the apex. -Mark Cernicky, Assistant Editor

A FRAMED, BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTO OF me cornering a 1992 CBR900RR hangs on my office wall. It remains there as a reminder of where leading-edge technology stood shortly after I came aboard at Cycle World 13 years ago.

Providing a lighter means to heavyweight performance, the RR not only redefined our perception of Open-class sportbikes, it also helped convince me the work was good around here. Perhaps I’d stay on awhile to see what we’d be riding next? The original RR swept our Superbike Shootout and earned a CW Ten Best award that year. I was blown away during the bike’s performance testing: 10.59 seconds at 132 mph at the dragstrip, 159-mph top speed, second-gear power wheelies! I also recall riding out a few intense tankslappers over bumps; luckily, the RR of the day only churned out 115 rear-wheel horsepower.

I can’t begin to imagine what I’ll be testing the day a faded, dusty photo of the CBR1000RR hangs on my office wall... -Don Canet, Road Test Editor

WHENEVER I RIDE A HONDA SPORTBIKE, I hear Dirk Vandenberg’s words ringing in my ears. The late American Honda R&D tester, tragically killed in an accident at Willow Springs five years ago, always stressed the importance of testing a sportbike on its stock tires before switching to sticky race rubber. “Bikes and tires are developed in unison,” he’d say. “That’s how we get that neutral steering feel.”

Sometimes, we dismissed Dirk’s concerns with the claim that racers were going to change tires anyway. But other times, like in the case of the VTR1000F, he was right-no other tires worked as well as the stockers.

So it’s odd to have the scenario we have here: two brands of tire, both approved for fitment as original equipment, yet each delivering a radically different steering feel. Rather than dismissing one or the other, however, I’ll merely suggest this: Should you buy a CBR1000RR, try it on whichever tires it comes on first. If you don’t like them, save them for a track day. Chances are they’ll work fine there.

-Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

HONDA CBR1000RR

$10,999

American Honda Motor Co., Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontArt of the Chopper

April 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Age of Tough Engines

April 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCutting It Close

April 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2004 -

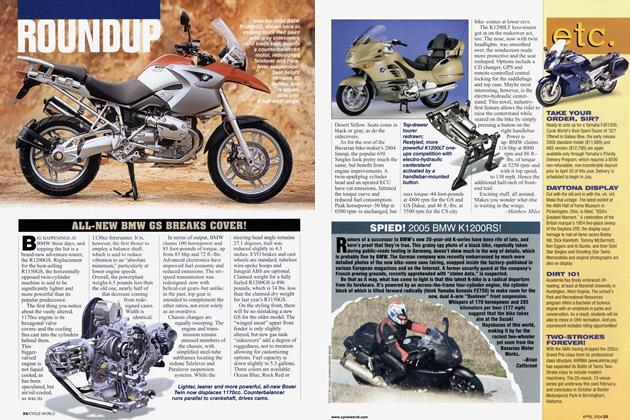

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Gs Breaks Cover!

April 2004 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! 2005 Bmw K1200rs!

April 2004 By Brian Catterson