GP four-strokes

TDC

Kevin Cameron

IN 2002, WE ARE GRANDLY TOLD, FOUR-stroke roadracers will return to the Grand Prix circus.

In fact, they never left. Four-stroke engines have always been legal in GP racing, but since Honda abandoned its oval-piston, 32-valve NR500 in 1981, no one has seen fit to enter one. Why no four-strokes now? The reason is that on an equal-displacement basis, the manufacturers believe four-strokes are uncompetitive. With 500cc two-strokes able to make more than 200 horsepower, it’s easy to see why. If we give our hypothetical 500cc four-stroke the same stroke-averaged combustion pressure as is currently achieved in Formula One, it would have to turn 28,000 rpm to make that power. To withstand the bearing loads generated at that speed, the crankcase would require a rigidity that can only come from weight. This makes us recall that the NR500 was once described by one of its patient riders as being “heavy as lead.”

Consequently, to make the fourstroke GP bike of 2002 competitive, it has been decided to give it 990cc. This reduces the rpm necessary to make 200-plus bhp to only 14,000-well within the proven capability of the stock crankcases already operating in AMA and World Superbike. This generous displacement allowance should make it easy for any manufacturer to achieve competitive power quickly.

Many commentators-including fivetime 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan-have enthusiastically endorsed the new rule, saying it will bring fresh variety and excitement to GP racing. Further, there are rumors of other engineering organizations expected to build sophisticated GP bike engines, among them BMW, Renault and Volkswagen. BMW already builds motorcycles, Renault has a connection with Benelli. It will be interesting to see these prestigious constructors come to grips with the problem of matching F-l-style engine power to the limited traction available on a motorcycle. With 990cc, four cylinders, an F-l-like bore-to-stroke ratio of 3:1 and normal combustion pressure, the result should come out somewhere close to 265 bhp. Now, feed that through existing tires in the class. No problem. These new builders will bring in not only F-l engine technology but also F-l-level funding.

Ah, funding. The top-spending F-l team’s annual budget is $330 million, while Honda’s emergency-level spending on the 1997 WSB chase (which John Kocinski did win) is rumored to have been between $10 and $17 million. According to its own published information, Aprilia currently spends about $22 million annually, spread over three GP classes and WSB. Ducati spends something similar on their various racing activities. The interesting point, however, is that even the top Honda figure, spent on a single class, is only five percent of the funding level of the top F-l spender. Will four-stroke GP bike engines and their chassis cost only five percent as much to develop as do top F-l engines and cars? Five percent of 10 cylinders-the number now universal in F-l-is half a cylinder. Five percent of four wheels (still traditional in F-1 ) is 2/îoths of a wheel.

It can't be that bad. Honda has hinted that its GP four-stroke will be developed in such a way that it will not only be competitive, but practical for privateers to operate and maintain. How about first showing us how easy this is to do in F-l? There, throwaway engines are now the rule because competition to achieve high power (800 bhp) and low engine weight (220 pounds) has made all parts absolutely marginal. One engine is consumed in each practice, and another in the race itself. Can anyone preserve this performance level in an affordable, privateer-maintainable package? Maybe we’re not really talking F-l technology here after all. Sounds a lot like WSB, actually.

But no, we are also told that all entries must be prototypes-no production-based equipment tolerated. This eliminates, presumably, such things as a slightly destroked Yamaha YZF-R1 with a pneumatic-valve cylinder head. The tech inspector’s role will be inverted. Instead of looking for trick parts, he will be on the lookout for anything suspiciously stock, such as a cadmiumplated steel split-washer.

F-l technology without the cost? Privateers? What is the value of a current factory Superbike, based as it is on production castings and chassis? It used to be that the figure loosely bandied about was $300,000, but that was several years ago. Now, the figure you hear is closer to $700,000. GP racing will be prototype only. That means more money. Who pays?

In F-l, it is mainstream major advertisers in a proven, established set of relationships. In present-day motorcycle GP racing, sponsors are not easy to find, even at the present, comparatively modest funding levels. Will fourstroke engines automatically inflate this to the necessary degree? Even if Honda’s GP design is privateer-friendly, will competitors agree to remain at that modest level of performance?

The more I hear about this, the more confused I become. F-l technology, but at less-than-WSB prices? I don’t think so. Non-F-1 technology, but no stock parts, at less-than-WSB prices? I don’t think so. Competitive privateers? They barely exist in WSB.

On the numbers, the 990cc rule makes it possible to achieve competitive power without F-l technology and materials. What does this mean? Could it mean WSB-level technology and materials? The more I think about it, the more it keeps coming back around to WSB.

The same thinking must be going on elsewhere, because the managers of WSB have suggested that they may resort to legal action if GP racing takes on a form barely distinguishable from their product. After all, the proposed 990cc four-stroke GP limit is only lOcc different from the existing upper limit for Twins in WSB. Enthusiasts like to think that racing is about racing, but in our world of television, it’s mainly about business. Business has rules, too.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontShameless Plugs

November 2000 By David Edwards -

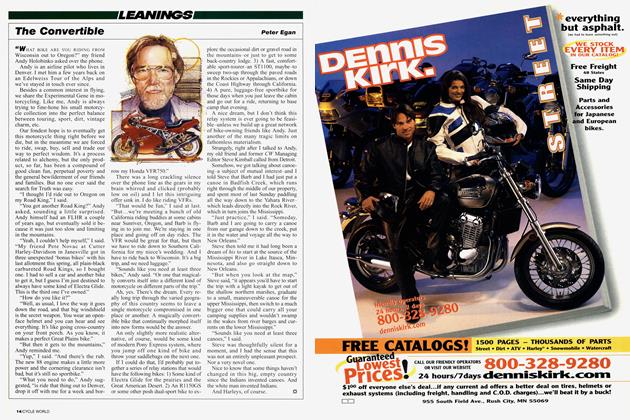

Leanings

LeaningsThe Convertible

November 2000 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupDan Gurney's Alligator: Alternative Corner Carver

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHart Attack

November 2000 By Eric Johnson -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

November 2000