Free bikes and other myths

UP FRONT

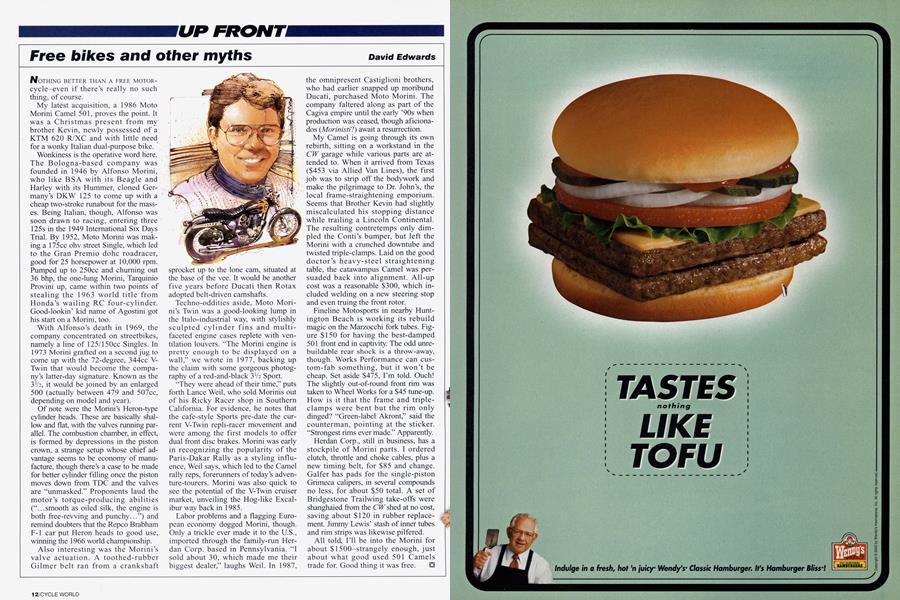

David Edwards

NOTHING BETTER THAN A FREE MOTORcycle—even if there’s really no such thing, of course.

My latest acquisition, a 1986 Moto Morini Camel 501, proves the point. It was a Christmas present from my brother Kevin, newly possessed of a KTM 620 R/XC and with little heed for a wonky Italian dual-purpose bike.

Wonkiness is the operative word here. The Bologna-based company was founded in 1946 by Alfonso Morini, who like BSA with its Beagle and Harley with its Hummer, cloned Germany’s DKW 125 to come up with a cheap two-stroke runabout for the masses. Being Italian, though, Alfonso was soon drawn to racing, entering three 125s in the 1949 International Six Days Trial. By 1952, Moto Morini was making a 175cc ohv street Single, which led to the Gran Premio dohc roadracer, good for 25 horsepower at 10,000 rpm. Pumped up to 250cc and churning out 36 bhp, the one-lung Morini, Tarquinio Provini up, came within two points of stealing the 1963 world title from Honda’s wailing RC four-cylinder. Good-lookin’ kid name of Agostini got his start on a Morini, too.

With Alfonso’s death in 1969, the company concentrated on streetbikes, namely a line of 125/150cc Singles. In 1973 Morini grafted on a second jug to come up with the 72-degree, 344cc VTwin that would become the company’s latter-day signature. Known as the 3*/2, it would be joined by an enlarged 500 (actually between 479 and 507cc, depending on model and year).

Of note were the Morini’s Heron-type cylinder heads. These are basically shallow and flat, with the valves running parallel. The combustion chamber, in effect, is formed by depressions in the piston crown, a strange setup whose chief advantage seems to be economy of manufacture, though there’s a case to be made for better cylinder filling once the piston moves down from TDC and the valves are “unmasked.” Proponents laud the motor’s torque-producing abilities (“...smooth as oiled silk, the engine is both free-revving and punchy...”) and remind doubters that the Repco Brabham F-l car put Heron heads to good use, winning the 1966 world championship.

Also interesting was the Morini’s valve actuation. A toothed-rubber Gilmer belt ran from a crankshaft

sprocket up to the lone cam, situated at the base of the vee. It would be another five years before Ducati then Rotax adopted belt-driven camshafts.

Techno-oddities aside, Moto Morini’s Twin was a good-looking lump in the Italo-industrial way, with stylishly sculpted cylinder fins and multifaceted engine cases replete with ventilation louvers. “The Morini engine is pretty enough to be displayed on a wall,” we wrote in 1977, backing up the claim with some gorgeous photography of a red-and-black 3V2 Sport.

“They were ahead of their time,” puts forth Lance Weil, who sold Morinis out of his Ricky Racer shop in Southern California. For evidence, he notes that the cafe-style Sports pre-date the current V-Twin repli-racer movement and were among the first models to offer dual front disc brakes. Morini was early in recognizing the popularity of the Paris-Dakar Rally as a styling influence, Weil says, which led to the Camel rally reps, forerunners of today’s adventure-tourers. Morini was also quick to see the potential of the V-Twin cruiser market, unveiling the Hog-like Excalibur way back in 1985.

Labor problems and a flagging European economy dogged Morini, though. Only a trickle ever made it to the U.S., imported through the family-run Herdan Corp. based in Pennsylvania. “I sold about 30, which made me their biggest dealer,” laughs Weil. In 1987,

the omnipresent Castiglioni brothers, who had earlier snapped up moribund Ducati, purchased Moto Morini. The company faltered along as part of the Cagiva empire until the early ’90s when production was ceased, though aficionados (Morinistil) await a resurrection.

My Camel is going through its own rebirth, sitting on a workstand in the CW garage while various parts are attended to. When it arrived from Texas ($453 via Allied Van Lines), the first job was to strip off the bodywork and make the pilgrimage to Dr. John’s, the local frame-straightening emporium. Seems that Brother Kevin had slightly miscalculated his stopping distance while trailing a Lincoln Continental. The resulting contretemps only dimpled the Conti’s bumper, but left the Morini with a crunched downtube and twisted triple-clamps. Laid on the good doctor’s heavy-steel straightening table, the catawampus Camel was persuaded back into alignment. All-up cost was a reasonable $300, which included welding on a new steering stop and even truing the front rotor.

Fineline Motosports in nearby Huntington Beach is working its rebuild magic on the Marzocchi fork tubes. Figure $150 for having the best-damped 501 front end in captivity. The odd unrebuildable rear shock is a throw-away, though. Works Performance can custom-fab something, but it won’t be cheap. Set aside $475, I’m told. Ouch! The slightly out-of-round front rim was taken to Wheel Works for a $45 tune-up. How is it that the frame and tripleclamps were bent but the rim only dinged? “Green-label Akront,” said the counterman, pointing at the sticker. “Strongest rims ever made.” Apparently.

Herdan Corp., still in business, has a stockpile of Morini parts. I ordered clutch, throttle and choke cables, plus a new timing belt, for $85 and change. Galfer has pads for the single-piston Grimeca calipers, in several compounds no less, for about $50 total. A set of Bridgestone Trailwing take-offs were shanghaied from the CW shed at no cost, saving about $120 in rubber replacement. Jimmy Lewis’ stash of inner tubes and rim strips was likewise pilfered.

All told. I’ll be into the Morini for about $1500-strangely enough, just about what good used 501 Camels trade for. Good thing it was free. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue