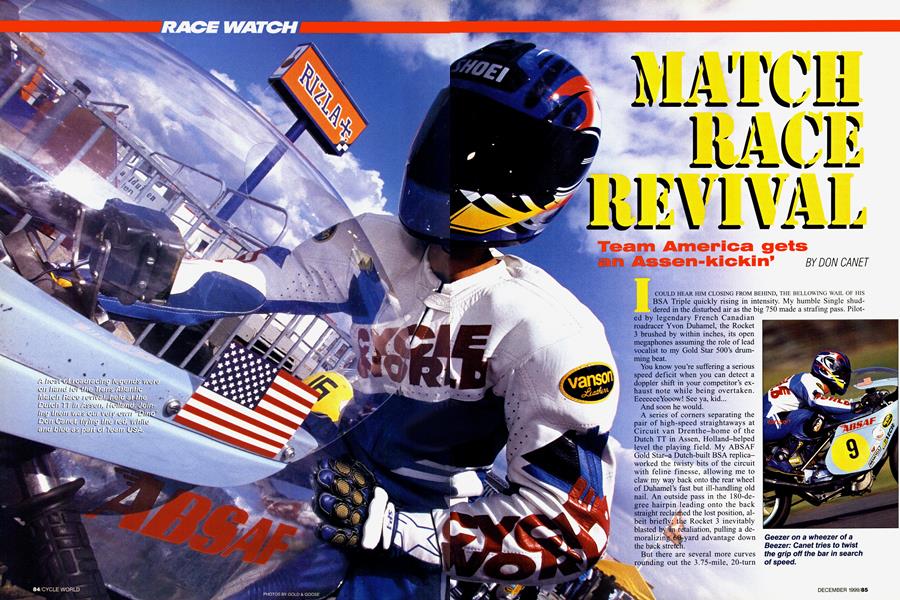

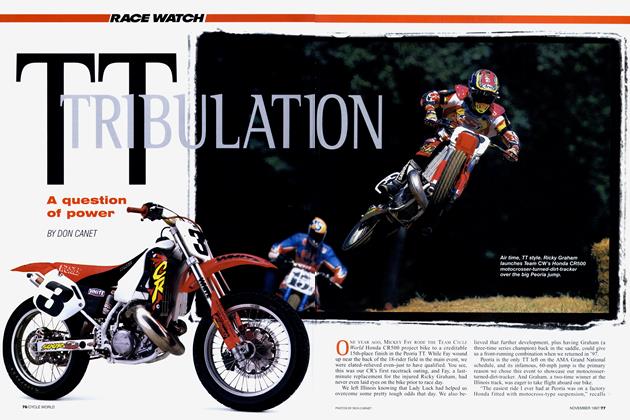

RACE WATCH

MATCH RACE REVIVAL

Team America gets an Assen-kickin'

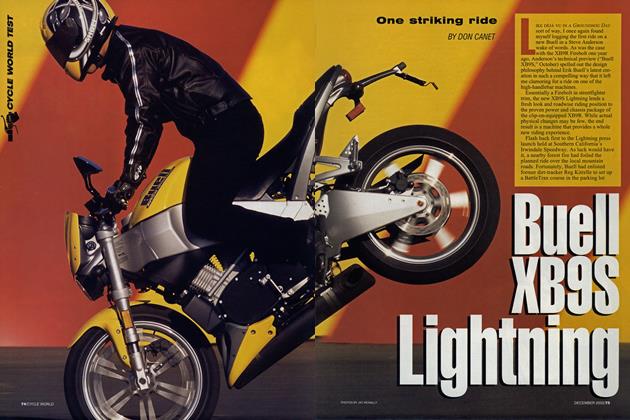

DON CANET

I COULD HEAR HIM CLOSING FROM BEHIND, THE BELLOWING WAIL OF HIS BSA Triple quickly rising in intensity. My humble Single shuddered in the disturbed air as the big 750 made a strafing pass. Piloted by legendary French Canadian roadracer Yvon Duhamel, the Rocket 3 brushed by within inches, its open megaphones assuming the role of lead vocalist to my Gold Star 500’s drumming beat.

You know you’re suffering a serious speed deficit when you can detect a doppler shift in your competitor’s exhaust note while being overtaken.

EeeeeeeYooow! See ya, kid...

And soon he would.

A series of corners separating the pair of high-speed straightaways at Circuit van Drenthe-home of the Dutch TT in Assen, Holland-helped level the playing field. My ABSAF Gold Star-a Dutch-built BSA replicaworked the twisty bits of the circuit with feline finesse, allowing me to claw my way back onto the rear wheel of Duhamel’s fast but ill-handling old nail. An outside pass in the 180-degree hairpin leading onto the back straight reclaimed the lost position, albeit briefly; the Rocket 3 inevitably blasted by in retaliation, pulling a demoralizing 60ryard advantage down back stretch.

But there are several more curves rounding out the 3.75-mile, 20-turn circuit, culminating with a tight rightto-left chicane preceding the start/finish straight. Light and nimble, my Goldie maneuvered to within striking distance of the larger BSA, setting up the perfect passing opportunity on the brakes entering the chicane, only to relinquish the hard-fought position as we accelerated through the gears past pit lane.

This seesaw battle wasn’t for a spot on the rostrum, nor anywhere near it. It was for ninth place, but it’s not often you get to mix it up with a famous racer aboard historic racebikes around a classic GP circuit. You can bet your most cherished heirloom I was savoring the moment, even if the race leaders were well out of sight. In the latter stages of the 30minute race, Duhamel came to grips with his quirky-handling machine and broke free of my pesky Thumper’s reach. But a few laps from the end, the man they call “Superfrog”-due to his hard-charging style back in the day when he rode factory Kawasakis-overcooked the right-hander at the end of the back straight, giving up time and track position as he took to the escape road.

After the race, I was in for some good-natured ribbing from the 59year-old. “I was thinking to myself out there, this guy is an amateur,” deadpanned Duhamel. “I shouldn’t be racing with an amateur.”

A bit of quick witticism was in order. “The way you were parking it in the turns,” I jabbed, “I was beginning to think Miguel might have been adopted.” >

Light-hearted banter was but one aspect of the fun-filled atmosphere surrounding this year’s Vanson Leathers Trans Atlantic Match Races. Organized by New York-based Team Obsolete Promotions, the Match Races were run as a support class during the Dutch TT-the seventh stop on the Grand Prix tour-and treated the 100,000-strong crowd to the sights and sounds of a bygone era.

The original Trans Atlantic Match Races were held annually during the Easter holiday, the first in 1971 and continuing into the ’80s. In those days, the format pitted an American team against a British squad in a six-race showdown held at a trio of U.K. circuits. Although the series provided some epic battles between the day’s top stars and factory bikes, it was eventually dropped from the calendar.

Having lain dormant for the past decade, the match-race concept was given new life under the Team Obsolete banner, along with an increased nostalgic appeal with the adoption of a historic-bike format. I traveled to the Netherlands as part of a nine-rider American team captained by T.O. lead rider Dave Roper. Other riders includ-

ed Duhamel, Cal Rayborn III, John Long, Malcolme Tunstall, Adam Popp, Erik Green and Johnny Kain. We were racing against an equal-sized team of Brits and a third team composed of 10 riders from various European countries.

The mix of machinery was interesting and diverse, with most of the Americans riding equipment borrowed from generous European benefactors. Nearly half the field rode F750-class staples—BSAs, Triumphs and Ducatis-along with kitted Hondas, Nortons, Laverdas and the odd ex-factory Harley-Davidson. These Twins, Triples and Fours were the hot race machines of the early 1970s. Among the 500-class bikes filling out the grid were a multitude of Matchless-powered Seeley G50 Singles, another ABSAF Gold Star like mine and an ex-Agostini MV Agusta 500 Triple ridden by Roper.

It didn’t take long for attrition to begin thinning the field, though. In fact, disaster struck by the third corner of practice. I was cruising along at a relaxed pace, unfamiliar with the bike and track, when a pair of European riders whizzed by on either side as though it were the last lap of a final. They were closely followed by Kain-except he was tumbling past in the grass, having been bumped off track by the over-zealous duo. Jeez!

So much for this being a “parade” for historic bikes...

Quite the contrary, actually. Truth > is, many of the guys were willing and able to push the limits of their aging machines. If the tires aren’t chattering through nearly every corner, then you just aren’t going fast enough!

Upon closer scrutiny, I learned that many of the bikes being raced in today’s historic events are actually recreations, mere silhouettes of period equipment. Modern materials and manufacturing processes have raised the performance bar and reliability of these “historic” racebikes. My own borrowed mount was a perfect example of this trend.

In the town of Appingedam, not far from Assen, is the Appingedam BSA Factory. The modest-sized facility produces complete, race-ready Gold Stars, and offers the parts needed to maintain them. Building something from the ground up is nothing new to ABSAF’s founder Nico Leeuwis, whose picture-frame-manufacturing business grew from humble beginnings in a barn to become the largest in all of Europe. Having vintage-raced original BSA Gold Stars into the early ’90s, Leeuwis grew frustrated with the difficulty of finding quality parts for the breed. In his quest, he hooked up with Jan De Jong, a crack machinist and Gold Star racing specialist.

Once engineering drawings of the Gold Star crankcase had been acquired from the original BSA foundry in England, ABSAF updated the castings for added strength. Many other remanufactured parts were then produced, tested and refined in De Jong’s

small machine shop. Cranks, rods, pistons, cylinder heads, barrels and much more were developed in-house before jobbing out production of proprietary components to various local firms. Some items, such as the Quaife six-speed gearbox and Bob Newby Racing clutch, still come from the U.K. The cylinder head is also cast in England before shipment to ABSAF for finish machine work. The frame, a Seeley Mk. Ill replica built from TIGwelded chromoly tubing, is crafted by De Jong himself. The Seeley-style fork with Manx-type dampers is another ABSAF creation, while a pair of American Works Performance shocks supports the rear.

Speaking of support, having the ABSAF factory located so near the track proved very beneficial. At night.

the bike returned to the shop for service and inspection. One morning, it even showed up with a different boreand-stroke configuration for me to try. Other riders were not so fortunate. Couple these sometimes fragile vintage racing machines with the surprisingly ample track time provided for what was really just a support class to

the GP, and it was almost like a vintage endurance race with overnight pit stops to regroup.

Popp and his Honda CR750 were a fast combo, but ran into problems from the first day. A local fan donated parts needed to repair the primary drive damaged in the opening practice session. In qualifying the following day, Adam’s motor popped again, this time dropping a valve. Unable to locate replacement parts, Popp and his crew chief, Mark McGrew, made a gallant effort to get the Honda back in the fray, albeit running on three cylinders. Interesting plan, but the dead cylinder pumped volumes of engine oil out the intake port. Mission aborted.

Rayborn was another no-show on the grid for the first race. Electrical problems plagued his Team Obsolete Harley-Davidson XR-750-the same bike raced by his late father 27 years > earlier-all week. Two days later, Rayborn made a bid for the lead in the opening laps of the second race, but once again was sidelined with ignition failure. A practice crash relegated Roper’s MV Agusta to its shipping crate prior to race two, while Kain returned to action following three days of reconstructive surgery on his battered Seeley G50.

Attrition holds to no nationality, however, as fastest qualifier Sandro Baumann’s Triumph Triple failed to start the first race due to fuel-delivery problems. Baumann, the Euro-team captain, was redeemed with a win in the second race. In a sort of role reversal, his Dutch teammate Hasse Gustafson won the first race, but sat out the second with a broken gearbox in his Ducati F750.

In the end, British team captain David Pither’s pair of second-place finishes aboard a Triumph 750 was enough to claim the Hailwood Trophy, awarded to the top individual points scorer. The Brits were also the topscoring team, with the Europeans second and the U.S...last. Oh well, I’ve

always held the belief that I’d rather play on the losing team than warm the winning bench.

And play I did, with an improved result of sixth overall and second 500 in race two. Better still, from where I sat I could see a battle up ahead involving Duhamel and the Triumph Triple ridden by John Long, who like Duhamel is a former AMA Pro and veteran of the original Match Races. Superfrog found his legs and leapt past on the 10th of 12 laps, but dropped out with an ignition failure, leaving Long unchallenged for the American team’s top honors. These are men I’ve read about in the history books of our sport, and to see them in action, racing as hard as this, was inspiring beyond words.

The Trans Atlantic Match Races at Assen served up more than just the sights and sounds of classic roadracing four-strokes, it brought together many of the people connected to that memorable era and presented them gloriously for a new generation to behold. You can always build more vintage racebikes, but the heroes who rode them are irreplaceable. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue