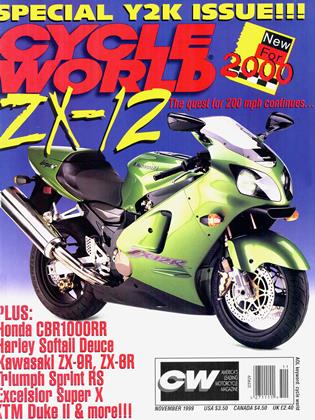

Mean G reenies

Kawasaki muscles up

STEVE ANDERSON

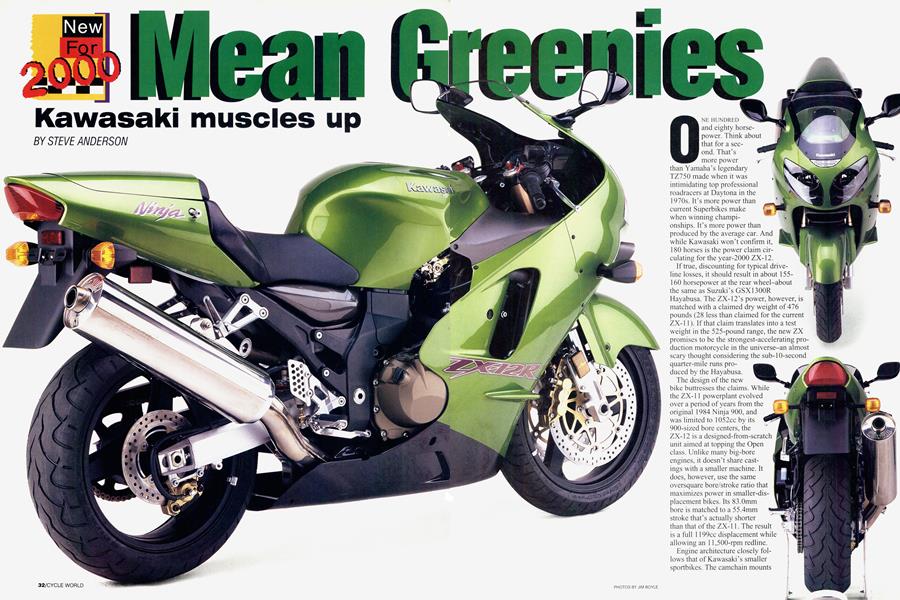

O NE HUNDRED `~~IuI~ and eighty horse power. Think about that for a sec ond. That's more power than Yamaha's legendary TZ750 made when it was intimidating top professional roadracers at Daytona in the 1970s. It's more power than current Superbikes make when winning champi onships. It's more power than produced by the average car. And while Kawasaki won't confirm it, 180 horses is the power claim cir culating for the year-2000 ZX-12.

If true, discounting for typical driveline losses, it should result in about 155160 horsepower at the rear wheel-about the same as Suzuki’s GSX1300R Hayabusa. The ZX-12’s power, however, is matched with a claimed dry weight of 476 pounds (28 less than claimed for the current ZX-11). If that claim translates into a test weight in the 525-pound range, the new ZX promises to be the strongest-accelerating production motorcycle in the universe-an almost scary thought considering the sub-10-second quarter-mile runs produced by the Hayabusa.

The design of the new bike buttresses the claims. While the ZX-11 powerplant evolved over a period of years from the original 1984 Ninja 900, and was limited to 1052cc by its 900-sized bore centers, the ZX-12 is a designed-from-scratch unit aimed at topping the Open class. Unlike many big-bore engines, it doesn’t share castings with a smaller machine. It does, however, use the same oversquare bore/stroke ratio that maximizes power in smaller-displacement bikes. Its 83.0mm bore is matched to a 55.4mm stroke that’s actually shorter than that of the ZX-11. The result is a full 1199cc displacement while allowing an 11,500-rpm redline.

Engine architecture closely follows that of Kawasaki’s smaller sportbikes. The camchain mounts on the right end of the crank, while a small alternator is on the left. The combustion chamber (described by Kawasaki as both a modified pentroof and a semi-hemi) depends in part on a dished piston and a very narrow included valve angle, and is taken directly from Kawasaki’s Superbike experience. The open-deck cylinder block is cast in one piece-separate from the top case half-with free-standing alu-

minum cylinders; a Nikasil-like coating provides a durable running surface while maximizing heat transfer. The cylinders tilt forward 20 degrees, positioning the downdraft intake system almost vertically. The gearbox is utterly conventional, without the

stacked-shaft design that so shortens Yamaha’s YZF-R1. And emphasizing the independence of this engine design, both the shaft spacing and gears are slightly larger than those of the current ZX-9R engine. As on the ZX-11, a twice-crank-speed counterbalancer helps fight the second-order vibration that often makes big inlineFours so buzzy.

To some extent, the ZX-12 poses an interesting question: Where does the engine stop and the frame start? Kawasaki’s engineers noted that airbox volume was rivaling that of the gas tank, and thought to do something doubly useful-like wrap the frame around it and make the airbox structural. Instead of twin spars, a single large-diameter beam comes back from the steering head over the top of the engine, widening as it goes. Fabricated from a combination of castings and sheet-metal stampings, the backbone also serves as the airbox. Ram air is routed through ducts reaching from the front of the fairing back into the sides of the backbone, and hence directly into the airbox. The air filter slides into a slot in the frame.

Fuel injection takes the place of carburetors on the ZX-12, with individual intake runners poking up through the bottom of the backbone; a bolt-on cover allows access for service. The injection system is a speed-density

design, so significant changes in engine tune will require reprogramming. A small catalyst in the exhaust system is fitted to all U.S.-bound ZX-12s, not just California models as in the past. But Kawasaki notes that the catalyst is actually a performance enhancer, allowing engineers to give the ZX-12 more cam timing and richer mixture settings than if they were attempting to meet emission standards without it.

Everywhere you look are serious attempts at weight reduction. Almost all engine covers, from the clutch to the sump, are cast in magnesium. The big muffler is fabricated inside and out from titanium. Parts have been eliminated, too. For example, the big ZX has no battery tray as such. Instead, the battery slides into a cast cavity in the frame. About the only things that haven’t been shrunk or downsized are the brakes: The front rotors retain the 320mm diameter as used on the ZX-11.

The 12 is shorter than the 11, though the exact measurement has yet to be released. The riding position is said to be very similar to that of the 9R, though perhaps slightly more upright. The seat-to-handlebar distance is shorter than that of the 11, and the handlebar ends are above top triple-clamp height. Better like the riding position, though: With the top clamp and bars cast as one, aftermarket alternatives may be a long time coming.

Unquestionably, the biggest ZX will be one of the quickest motorcycles made. Will it also be the fastest? That’s as dependent on the quality of its aerodynamics as its power, and while its mirrors and clean overall shape hint that much attention was paid to drag, only testing will tell if it can match or beat the Hayabusa’s 194-mph measured top speed. All a Kawasaki spokesman would say on that matter was: “We didn’t build it to be slower than the Suzuki.”

While the ZX-12 brings fundamental

change to Kawasaki’s biggest sportbike, the new ZX-9R ZX-6R have evolved

from last year’s models, with substantial improvements but not all-new designs. Both get new fairings with a shared twinheadlight layout, one that presents a more sinister face to the world. The 9R gets substantial changes to both engine and chassis to back up that angry new look. Compression is up, and there’s a new cylinder head with redesigned combustion chambers. Cam timing is lengthened, a new ram-air system increases air pressure to the engine, and the intake system is longer while the exhaust header is both longer and larger in diameter. As on the 12, an exhaust catalyst allows richer mixtures on 49-state models. The overall result is a slight boost in power with much smoother delivery.

Changes to the 9’s chassis-such as the longer steering-head pipe and matching taller twin spars and the larger-diameter axles and swingarm pivots-essentially increase stiffness or add features demanded by racers, such as the removable subframe, shock ride-height adjuster and 190/50-17 rear tire on a 6-inchwide rim. Lighter parts, such as the linerless, all-aluminum cylinder block and the extruded legs of the aluminum swingarm, compensate for the frame changes and bigger 310mm brakes.

The 6R, in contrast, gets fewer chassis changes but pumps some additional iron in the engine bay, all while dieting. Weight reductions are numerous, from a lighter crankshaft that maintains the same flywheel inertia as last year (with thinner, larger-diameter crank webs), to a narrower clutch with thinner plates, to a new swingarm similar to that of the 9R. Overall, the 6R has shed around 7 pounds. Power comes from more compression (a whopping 12.8:1; both the 6R and the 9R now require 90-octane gasoline), longer cam timing, and subtle tuning tweaks such as the slightly shorter intake tract. Kawasaki claims about a 11/2 horsepower increase. Other improvements are yet more subtle, such as the lightweight, thin, stepper-motor-controlled tachometer and speedometer, and the front brake calipers with differential-bore pistons. By dropping the size of the leading-edge piston to 24mm, Kawasaki was able to give the 6R more aggressive, higher-friction pads yet improve feel on initial brake

application. With all of the performance that Kawasaki is claiming from its year2000 Ninjas, improvements to braking power and controllability may be the most essential of the bunch. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe X Factor

November 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat Your Bike Says About You

November 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWomen In Racing

November 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Hotshots

November 1999 -

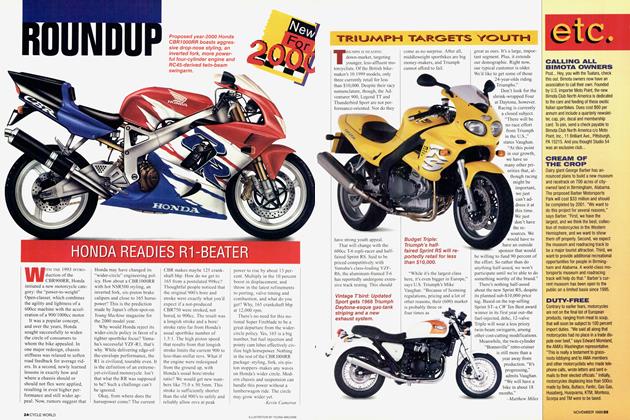

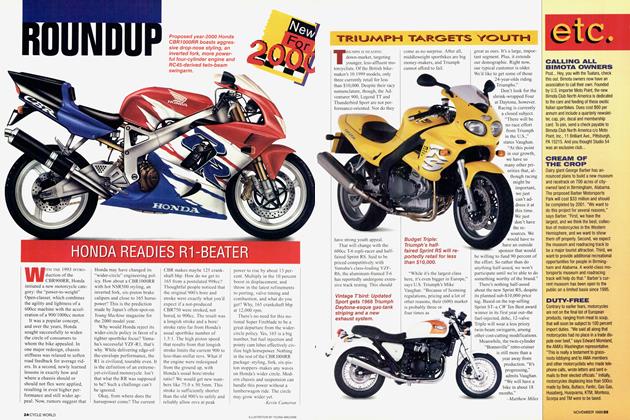

Roundup

RoundupHonda Readies R1-Beater

November 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph Targets Youth

November 1999 By Matthew Miles