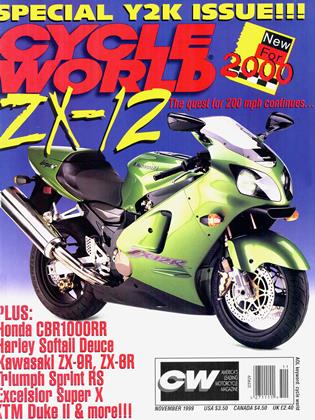

EXCELSIOR-HENDERSO N SUPER X

CYCLE WORLD TEST

From Sturgis to the sea on the Minnesota mega-cruiser

SIX YEARS AGO, THIS MOTORCYCLE WAS nothing more than an idea, and a crazy one at that, bouncing around in the heads of two brothers who didn't really know any better. Today, it's the calling card of a $100 million company just beginning its second model year of production.

This has not been easy. Anyone can (and has, it seems) order up an Evo-lookalike motor, pluck parts from the Harley aftermarket and come up with a fairly decent hybrid Hog. But every part on the Excelsior-Henderson Super X cruiser is purpose-built, designed inhouse or supplied by vendors to company specs. And that wasn’t

the toughest part. Before one bike could be built, there was an assembly plant to erect, offices to outfit, a state-of-the-art paint facility to set up, a workforce-240 strong at this point-to hire and equip and train. Everything was more involved, more difficult than expected. You haven’t experienced red tape until you’ve run up against the EPA, the DOT and OSHA, not to mention state and local regs. All this in just over five years-or about the same time it took HarleyDavidson to develop its new Twin Cam 88 motor alone.

Money has been an issue all along, the company devouring more investment dollars than co-founders Dan and Dave Hanlon (along with Dave’s wife, Jennie) ever dreamed. The factory itself ate up a cool $30 mil. Excelsior-Henderson weathered one financial crisis last spring when a quick $10 million had to be raised, and as this is written in late August the company is facing more fiscal hurdles (see “The X Factor,” Up Front, this issue).

Ask Dan, Dave and Jennie if, knowing what they know now, they would do it all over again, and the Family Hanlon has to think long and hard before answering.

And yet, against all odds, E-H has built and shipped to dealers more than 1000 Super Xs. Cycle World road-tested one of the first year-2000 models off the assembly line, riding from the factory in Belle Plaine, Minnesota, to the Sturgis Rally in South Dakota and then on to Southern California, a total of almost 3000 miles on everything from desolate dirt roads to twisty two-lanes to desertcrossing interstates.

Two pilot-production 1999 Super Xs we’d sampled previously had a not-quite-ready-for-prime-time feel, the main culprit being excessive vibration from the 1386cc, non-counterbalanced engine. This was bad at high cruising speeds and especially on deceleration-when it felt like a

motor-mount bolt had come adrift. For Y2K, the connecting rods and crank were rebalanced, the frame was reinforced to alter its harmonics, and the rubber engine mounts were modified. The effect is dramatic. Excelsior’s 50degree V-Twin still shakes, but between 2000 and 3000 rpm (an indicated 60 to 80 mph in top gear), things smooth out considerably, making the Super X a willing highway flyer. Run the tach on up to its 5500-rpm redline and the vibes increase in amplitude, but are nowhere near the jackhammer levels of the early ’99s.

We weren’t overly enamored with those first bikes’ gearboxes, either, thanks to a frustratingly elusive neutral. Our testbike’s tranny was better. Neutral is easier to snare, though it’s still best done on the run-and then occasionally the 2-1 downshift resulted in an unwanted green light. Room for further improvement here.

Ditto the oil-checking procedure. A dry-sump design, the “X-Twin” is fed lubricant from an underseat oil tank, its level checked with a 17-inch dipstick located on the right side. To ascertain oil level, the owner’s manual calls for the engine to be at normal operating temperature (whatever that is), transmission in neutral, the bike straight up and down. The engine is to be started and run at 25003000 rpm for 30 seconds, shut off while the bike is still upright, then the whole plot gets leaned over on its sidestand for the ritual dipstick scrutiny. Convoluted. Worse, it doesn’t work, at least not on our bike. We checked oil three times out on the road-once after a short morning warm-up, once after an hour’s ride and once at the end of a hard, 750-mile day-and each time the level showed low enough to add a quart of 20w-50. Which we dutifully did, only to be rewarded with oil streaming out of the airbox breather and all along the side of the bike. So what was it, too low or overfilled? ExcelsiorHenderson suggested we weren’t checking the oil in the prescribed manner. We were. Our local dealer came to the rescue; a customer’s Super X had suffered the same messy malady. Turns out some bikes were shipped with dipsticks that are too short! After that, as long as some wetness showed on the stick we left well enough alone. Exxon Valdez impersonations notwithstanding, our testbike made a pretty good cross-country traveling companion, mowing down mile after mile at 70-75 mph, smack in its vibration sweet spot. Upping the comfort quotient is the Super X’s signature front end, a formidable leading-link affair with 4 inches of travel. Love its looks or hate ’em-there seems to be a 50/50 split-the easy-steering, stictionless fork flat works, constantly in motion soaking up road irregularities. Only sharp-edged bumps confuse the fork, which emits a thunk at high speeds and a cute ring around town, almost as if you’re checking into a hotel and need to get the desk clerk’s attention. Thumbs-up also for E-H’s accessory touring package (well, except for the one running light’s rivets, which came loose and allowed the shell to jostle about). Particularly useful for long days in the saddle is the copbike-style, height-adjustable windscreen. Positioned in the first (of six) settings, it’s low enough that sub-6-footers can easily see over. The touring options also pay visual dividends: First, they mitigate the fork’s mass, focusing attention back on the engine; second, they play up the Super X’s intended retro theme. In red and silver, the bike hints of a ground-bound Waco biplane-come to think of it, that front fender does resemble a landing-gear spat... Some random observations from the road: The owner’s manual does not kid when it stipulates 92-octane unleaded. Forced to fill up with low-number swill in some backwoods burg, we were greeted with pinging like the Castanets from Hell. Actually, even on the good stuff, the

Super X has a tendency to detonate on hot, uphill climbs.

Speaking of which, the Super X did not take kindly to the Continental Divide. Hauling 250 pounds of rider and luggage, and pushing its sheet of plexi into a strong headwind, our testbike struggled to hold an uphill 70 mph at full throttle. Part of the problem is a tall fifth gear-almost an overdrive-which undoubtedly helps with the bike’s flatland aplomb but kills top-gear performance (60-80-mph roll-ons take a glacial 9.6 seconds, almost twice as long as a Twin Cam Harley). A quick downshift is your friend in any passing maneuver.

Not helping is the Super X’s weight. Gassed up, it nudges past 800 pounds. Figure 30 pounds for the touring gear and that’s still 70 pounds heavier than last month’s test H-D Fat Boy, not exactly the Calista Flockhart of the two-wheeled world.

Cornering clearance remains less than optimum, especially on the right side, where the floorboard folds up begrudgingly, but its mounting bolt and the lower muffler do not. If you insist, the Super X can be hustled down a gnarled backroad, but it’s sort of like teaching Roseanne Barr how to surf-not a pretty sight and sooner or later there’s gonna be a big splat. Of course, if decking hardware were a crime in the cruiser world, most of the lot of ’em would be pulling time in the Big House.

So, the Hanlons have come a long way-farther than many so-called experts predicted-but their cruiser is not all it could be. That’s the bad news. The good news is that for a company that quite literally started from scratch, the job of refining the Super X, of finding a few more horsepower, dropping some weight, tweaking the transmission, etc. ought to be a piece o’ cake. From our vantage point, the good far outweighs the bad. □

EDITORS' NOTES

WITH A LABORED GROAN, I MUSTER A clean ‘n’ jerk move in hoisting the Excelsior Henderson Super X up off its sidestand. My bulging neck veins leave little doubt the bike is packing some serious weight. Without a spotter standing by, I ease the beast onto a narrow ramp positioned like a seesaw atop CWs certified Detecto scale. With its engine pounding out a fast idle, I finesse the clutch and brake while carefully ushering the Super X up the ramp until it teeters forward and balances upon the scale. Yeow! At 807 pounds gassed up, the Super X would mark the spot of my demise if it were to tip my way. But hey, road-hugging weight can be a desirable trait in a big-inch cruiser. Although it may not float like a butterfly, once underway, this super heavyweight feels lighter on its feet than its official weigh-in would indicate. Just be grateful that insurance premiums are not quoted by the pound. -Don Canet, Road Test Editor

WELCOME TO THE GOOD OL’ U.S. OF A., where bigger is better, four-wheel-drive land yachts masquerade as commuter vehicles and real-steel boulevard bikes vie for heavier-than-thou honors. Latest incarnation of the latter is the long V large Super X, a Midwest-minted VTwin that makes last month’s H-D Softail Fat Boy look like a minicycle. Will it ever end? Before you get all chapped and mark me as anti-cruiser, know this: Once past the parking-lot weigh-in and out on the open road, the Hanlon Special is a pretty good ride, stiff clutch and numb rear brake aside. The big-inch engine makes competitive power and is pretty smooth at legal speeds. Moreover, the bike boasts what may be motorcycling’s most entertaining front end, an exposed-spring monstrosity that, while spectacularly soaking up superslab whoop-de-doos, is forever engaged in a delightfully hypnotic dance. Size notwithstanding, ftm springs eternal. -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

WHEN THE HANLONS EMBARKED ON this quest half a decade ago, their mission statement was simple: Build an American-made alternative to HarleyDavidson, and while we’re at it, give the thing more power, stronger brakes and better suspension. Mission accomplished-if the target was the old Evolution Big Twin. Trouble is, the cruiser landscape has changed. The new Twin Cam Harley, better braked and better forked than before, makes as much or more horsepower than the Super X’s 59 bhp, plus it pounds out an additional 4-5 foot-pounds of torque, is about a second quicker in the quarter-mile and has at least 10 mph in hand past the radar gun. Now it seems like all you get for the Excelsior’s double-overhead-cam, four-valve trickness is a more clattery top-end. (“I can always tell when a Super X pulls into the parking lot,” said one dealer.) But it would be a mistake to count out the Super X. While you’re sleeping, the Hanlons are hard at work... -David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief 44/CYCLE WORLD

E-H SUPER X

$18,690

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

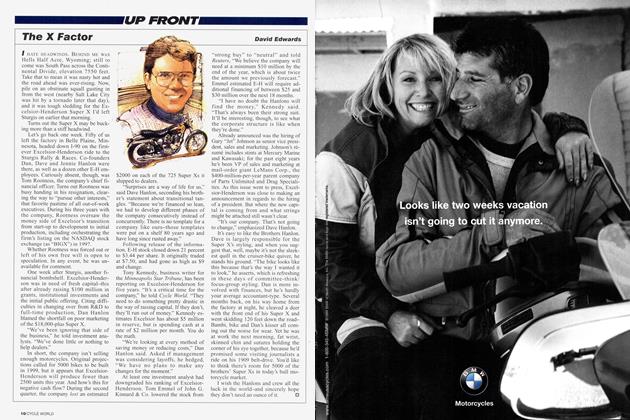

Up FrontThe X Factor

November 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat Your Bike Says About You

November 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

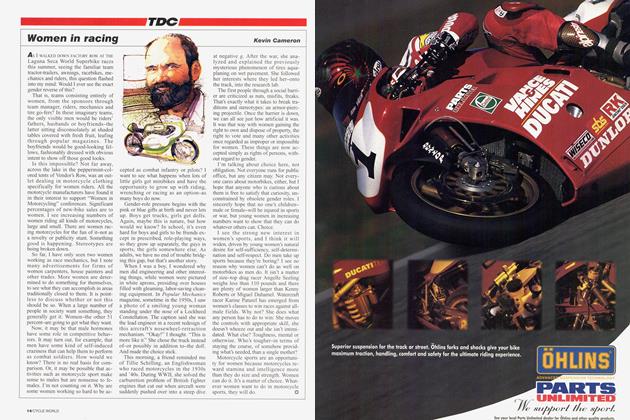

TDCWomen In Racing

November 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Hotshots

November 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Readies R1-Beater

November 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph Targets Youth

November 1999 By Matthew Miles