HONDA CR250R

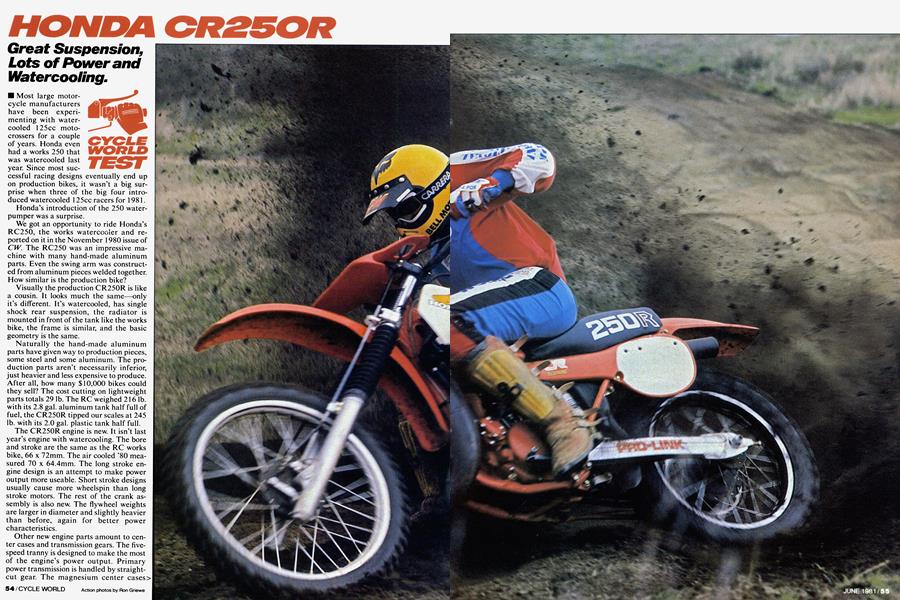

Great Suspension, Lots of Power and Watercooling

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Most large motorcycle manufacturers have been experimenting with watercooled 125cc moto crossers for a couple of years. Honda even had a works 250 that was watercooled last year. Since most suc cessful racing designs eventually end up on production bikes, it wasn't a big sur prise when three of the big four intro duced watercooled 125cc racers for 1981.

Honda's introduction of the 250 waterpumper was a surprise.

We got an opportunity to ride Honda's RC250, the works watercooler and reported on it in the November 1980 issue of CW. The RC250 was an impressive ma chine with many hand-made aluminum parts. Even the swing arm was constructed from aluminum pieces welded together. How similar is the production bike?

Visually the production CR25OR is like a cousin. It looks much the same-only it's different. It's watercooled, has single shock rear suspension, the radiator is mounted in front of the tank like the works bike, the frame is similar, and the basic geometry is the same.

Naturally the hand-made aluminum parts have given way to production pieces, some steel and some aluminum. The pro duction parts aren't necessarily inferior, just heavier and less expensive to produce. After all, how many $10,000 bikes could they sell? The cost cutting on lightweight parts totals 29 lb. The RC weighed 216 lb. with its 2.8 gal. aluminum tank half full of fuel, the CR25OR tipped our scales at 245 lb. with its 2.0 gal. plastic tank half full.

the UK2~UK engine is new. It isn't last year's engine with watercooling. The bore and stroke are the same as the RC works bike, 66 x 72mm. The air cooled `80 mea sured 70 x 64.4mm. The long stroke en gine design is an attempt to make power output more useable. Short stroke designs usually cause more wheelspin than long stroke motors. The rest of the crank as sembly is also new. The flywheel weights are larger in diameter and slightly heavier than before, again for better power characteristics.

Other new engine parts amount to cen ter cases and transmission gears. The five speed tranny is designed to make the most of the engine's power output. Primary power transmission is handled by straightcut gear. The magnesium center cases were designed so they would work for the 250 as well as the open bike. The basic castings are the same—machining differences determine whether the cases will be for a 250 or 450. The clutch is the same for both engines also.

The smooth outer surfaces of the head and cylinder give an impression of smallness at the top of the CR engine. And the lack of fins definitely makes things less crowded, although the plumbing for the water uses some of the room gained. Honda’s watercooling system requires more hoses and connections than other designs.

Honda uses two small aluminum radiators, one on each side of the frame’s backbone. Thus, extra hoses are needed to tie all the pieces together. The filler neck is placed between the radiators, a short piece of hose connects it to each radiator. Water is pumped through the system by a single primary gear driven pump. The bottom of the left radiator furnishes water to the pump. The pump pushes water through the cylinder, then the head, then up to the right radiator where it enters the bottom and exits the top on its way through the filler spout to the top of the left radiator. The cooling system holds 1.3 qt. of water and antifreeze mixed. The pump runs at a 1:1 ratio to the crankshaft and circulates 52 qt. of water a minute at 7500 rpm. Engine temperature runs between 192°194° when the air temperature is 86°.

Stabilizing engine temperature is the primary reason for using watercooling. The complexity of the cooling system is a fair trade for the benefits gained. When an engine runs within a given heat range, engine tolerances can be closer, meaning the piston to cylinder clearance can be tighter. A tighter bore means more power can be produced and because the cylinder won’t distort due to heat, power can be maintained throughout a long moto. Honda’s tests with engines running wide open on engine dynos have shown air cooled engines lose up to 30 percent of their power from heat distortion during the first 20 min. The same engine with water cooling only loses 10 percent. That’s quite a difference. The last benefit from water cooling is extended engine life. Pistons and rings and cylinders all stay round longer, a critical factor for longevity.

Having an engine that makes lots of power over a long period of time is half the battle. To fully use the engine a good chassis is required—the Honda has one. It’s chrome-moly steel, has good triangulation under the seat, and a large diameter backbone tube. A large front downtube splits into two smaller tubes that roll under the engine and terminate at the rear of the backbone. Boxed gussets are abundant around the steering head and above the upper shock eye. The design is much like the RC racer and almost exactly the same as used on the CR450R. The only difference between the 250 and 450 frames is the extra bracketry for the radiator on the 250.

The aluminum swing arm is an extrusion, not welded up small pieces like the RC. The production part is strong and well made but it’s probably heavier than the factory racer’s part. Probably a lot cheaper to manufacture and replace also. It looks the same as the 450 swing arm but the 250 arm is about a half inch shorter.

First class suspension is standard at both ends of the CR. The rear is Honda’s new Pro-Link. A large bodied Showa shock is placed nearly vertical at the extreme rear of the frame which is the extreme front of the swing arm. The top of the shock is positioned at the rear of the frame’s backbone, the bottom rides in the Pro-Link arms. Honda’s system is probably the least complex of the monkey-motion single shock systems. The Pro-Link levers don’t move nearly as much as the other systems. In fact, the lever’s main function is moving the lower shock eye upward about 1.5 in. as the swing arm nears full compression. The action speeds internal shock piston speed, which increases damping force as the shock nears the end of its travel. Thus the system has a built-in mechanical progression, eliminating harsh bottoming. The lever arms are chrome-moly steel, not aluminum like the works bikes. Bushings for the Pro-Link levers vary depending on where they are. The top shock eye is a steel bushing without a seal. The lower shock eye mounts to a rubber bushing at the center of the ProLink arm. Both ends of the torque arm and the upper part of the arm that pivots in the swing arm, are equipped with bronze bushings and good grease seals. Disassembly is required for inspection and greasing. Since the parts don’t move much and the seals do their job, tear down for greasing isn’t required often.

The large steel bodied Showa shock is an oil/gas unit with four rebound damping adjustments. The adjuster wheel is located in the bottom clevis and it’s hard to reach. It has the positions marked on the plastic wheel but you can’t read the numbers unless the shock is off the bike and turned upside down! Each position has a detent click but it’s not a very positive click. Care must be exercised when making the adjustment or it’ll end up between clicks. If stopped between clicks, the shock action will be the same as if set on number four, the stiffest rebound position. Fortunately the shock won’t need adjustment often. We liked the number two click for motocross, number one for off-road riding. Spring preload is accomplished by turning the ring at the top of the shock spring. We liked it set slightly softer than delivered. Lots of adjustment is available and Honda has softer and stiffer springs available as options. An aluminum shock reservoir is placed on the left side of the frame. The reservoir is finned but it doesn’t need the finning for cooling—it’s almost completely full of nitrogen inside a rubber bladder. Just the top has oil in it at full extension, although it does fill some when the shock is compressed. We understand the unit is pressurized to approximately 290 psi but Honda doesn’t recommend checking pressure or changing oil. They even hide the air valve under a plate at the end of the reservoir. Honda recommends throwing the shock away when used up. Seems a shame not to be able to rebuild it or even change oil.

Forks are leading axle KYBs with 12 in. of travel. Stanchion tubes are a healthy 41mm in diameter. Internally two DUtype bushings ease friction and ensure smooth action. Honda recommends running some air in the forks. We found 3 psi perfect. A note of caution—adjust air pressure 1 psi. at a time with the front wheel off the ground. Experimenting with 3 or 4 psi jumps has been standard practice in years past—the new larger diameter stanchions are sensitive to 1 psi changes. In fact the Honda’s forks became too soft when set at 2 psi, too stiff set at 4 psi! Ten weight oil set at the recommended level, 6.6 in., proved perfect for our racers.

Wheel assemblies are a highlight on the CR. Both are better than the ones the factory RC racer used last year. The front is a double leading shoe that’ll stop on a dime. The rear is a single leading shoe with a full-floating backing plate. Both hubs are nice strong units with the right size spokes and good aluminum rims. Even the tires are good. The Bridgestones work on a variety of terrain and give reasonable life.

Plastic components are first class on the CR. The fenders are large and shaped right, the side numbers don’t protrude or hamper work on the bike, the tank holds enough fuel. The air cleaner is behind the shock. Air is routed to the right side of the off-set shock. Cleaning the filter requires removal of the seat. The foam is difficult to get out :>f the box as it has to be turned crosswise. We found it easier to take off the complete box first. It is held in place by a 6mm screw at each side. Removing them and loosening the clamp at the back of the carburetor will allow removal of the box. Then it’s an easy job to clean the filter and inside of the box. Removing the complete unit is good insurance anyway. The air hose and carburetor are lower than the filter so dirt that gets knocked off the used filter ends up in the pot-bellied air hose. Getting the dirt out of the hose requires disconnecting the hose from the carburetor and removal of the carb . . . it’s quicker and easier removing the box.

Controls on the CR are designed well and won’t need replacement. The aluminum shift lever has a steel tip that folds, (a rubber tendon is used instead of a steel return spring) the aluminum rear brake pedal has a steel tip, the hand levers are forged aluminum and dog-leg shaped, the throttle is a straight-pull design and the kick start lever has a ribbed non-slip end. Attention to detail goes more than skin deep on the CR. Little things that go unnoticed on the dealer’s floor are much appreciated when the bike is used for a while. The rear brake pedal and kick lever have seals on their pivots so grease is kept in, dirt out—they won’t stick and get jammed from mud. The hand lever pivots are protected from the elements by small rubber guards and the control cables are quality items that’re well routed.

The CR250R is a one kick starter. Doesn’t matter whether the engine is hot or cold, one kick almost always does it. Once running, don’t be in hurry to ride away, water cooled engines require more warm-up time.

Honda’s CR250R is a little porky for a 250cc motocrosser. At 245 lb. with a half tank of premix, the CR is 12 lb. heavier than a 1981 YZ250H, 20 lb. heavier than an ’80 Maico, 21 lb. heavier than an ’80 RM and 8 lb. heavier than an ’80 KX250. Funny thing is, the weight isn’t noticed while riding the bike. The low placement of the shock and Pro-Link levers mask the weight. All our riders thought the bike handled like a 210 lb. bike. Like most modern motocrossers, the CR has a tall seat height. But the 38 in. height isn’t as bad as it sounds. The suspension sacks a couple of inches once the rider is aboard and makes the height more comfortable.

The CR’s engine is strong but most of the strength is in the upper range. Honda has mated a close ratio five-speed transmission to the engine and the combination works well. The close ratio trans makes it easy to keep the engine on the pipe and the landscape rushing past. The peaky engine and close ratio gearbox mean the rider has to shift often, much like riding a 125. Ridden like a 125 the CR will easily pull the hole shot. And it’ll out-drag many ported motocrossers. We even got the hole shot in a pro race with it.

HONDA

CR25OR

The CR is great in corners. It’ll go anyplace the rider wishes. High, low or the middle, the bike doesn’t care. If corners are smooth and flat the rider has the option of sliding them TT style. The rear wheel will jump out just so far and then stick like glue as the bike goes through full-lock. Making square turns is a CR specialty. Just start the turn, the bike will complete it. The CR250R is lightning quick in such turns. Amazing for a bike with a wheelbase in excess of 59 in. The rear suspension is responsible for the catlike quickness when changing directions. Placing the shock and other suspension parts low and in the center of the chassis makes changing direction easier.

The CR also handles well over jumps. Balance is right on and the bike flies true and straight. Landings are soaked up nicely by 12 in. of controlled travel at each end. Forks are some of the best ever put on a production bike. Small and large bumps go unnoticed. The rider never gets jarred or bounced around. And the rear is almost as good. The built-in progression allows a soft primary suspension rate and a stiff final rate. So the rear end of the bike rolls over small obstacles easily yet doesn’t bottom harshly landing from large jumps.

Riding position is great. The bar, seat, pegs, shift lever, brake pedal, and general placement of the controls fit most riders perfectly. Crawling around on the bike to make it work is optional. It’ll work fine if you do, it’ll work fine if you elect to sit in one spot. The CR is narrow. The vertically placed shock means the chassis can be narrow and the rider’s knees don’t have to be spread to straddle the CR.

Brakes are as impressive as the rest of the bike. The double leading shoe front and full-floating rear quickly and controllably stop the CR. Lever pressure is just right, not too easy, not too hard.

Starts are a little touchy on the CR250R. Second gear starts work if the ground is hard and slippery. If the ground is tacky or loamy, the CR will leap out of the gate then fall flat on its face as soon as the 5.10 rear tire hooks up. Low gear has to be used for that kind of soil. The problem is the large rear tire. It’s simply too big for the combination of a 250cc engine, second gear starts and loam. Switching to a smaller rear tire will make second gear starts easier if your track is loamy. Otherwise, use low and shift to second as soon as the bike leaves the gate.

Honda’s first year production 250cc waterpumper has to be rated a success. It doesn’t have the lightness or the sheer mid-range horsepower of the works RC water pumper, but it’s competitive against the other production bikes and it offers the buyer something no other 250cc motocrosser does—a radiator. EB

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontInnocence Vanquished, Fatherhood Victorious

June 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1981 -

Department

DepartmentRoundup

June 1981 -

Competition

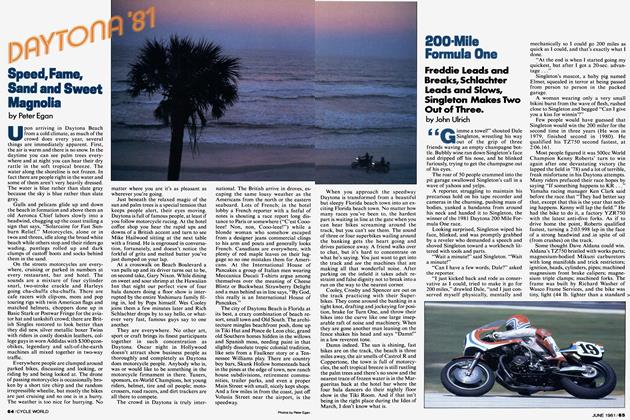

CompetitionDaytona'81 Speed, Fame, Sand And Sweet Magnolia

June 1981 By Peter Egan -

Competition

Competition200-Mile Formula One

June 1981 By John Ulrich -

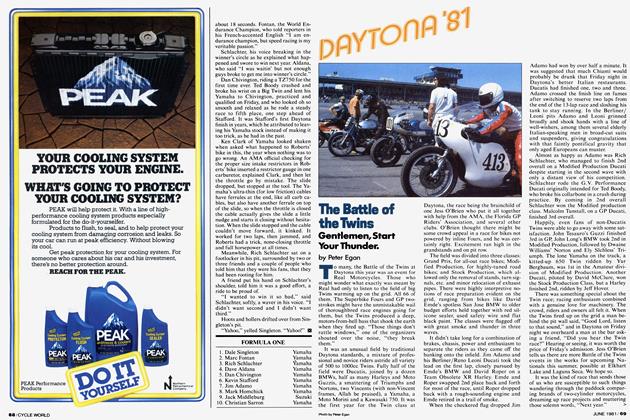

Daytona'81

Daytona'81The Battle of the Twins

June 1981 By Peter Egan