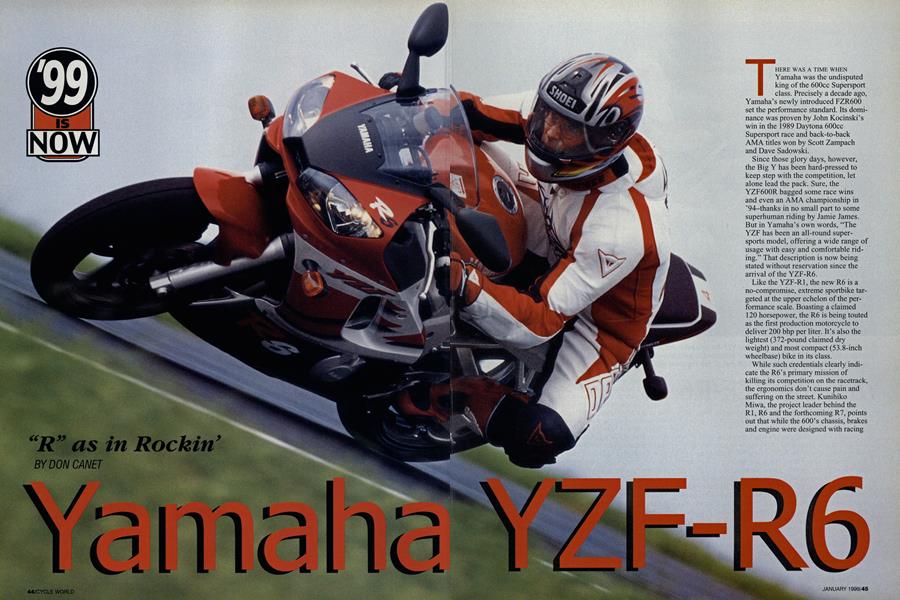

Yamaha YZF-R6

"R" as in Rockin'

DON CANET

THERE WAS A TIME WHEN Yamaha was the undisputed king of the 600cc Supersport class. Precisely a decade ago, Yamaha’s newly introduced FZR600 set the performance standard. Its dominance was proven by John Kocinski’s win in the 1989 Daytona 600cc Supersport race and back-to-back AMA titles won by Scott Zampach and Dave Sadowski.

Since those glory days, however, the Big Y has been hard-pressed to keep step with the competition, let alone lead the pack. Sure, the YZF600R bagged some race wins and even an AMA championship in ’94-thanks in no small part to some superhuman riding by Jamie James. But in Yamaha’s own words, “The YZF has been an all-round supersports model, offering a wide range of usage with easy and comfortable riding.” That description is now being stated without reservation since the arrival of the YZF-R6.

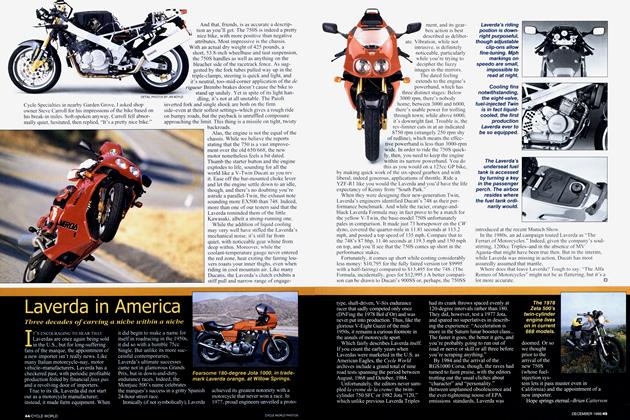

Like the YZF-R1, the new R6 is a no-compromise, extreme sportbike targeted at the upper echelon of the performance scale. Boasting a claimed 120 horsepower, the R6 is being touted as the first production motorcycle to deliver 200 bhp per liter. It’s also the lightest (372-pound claimed dry weight) and most compact (53.8-inch wheelbase) bike in its class.

While such credentials clearly indicate the R6’s primary mission of killing its competition on the racetrack, the ergonomics don’t cause pain and suffering on the street. Kunihiko Miwa, the project leader behind the RI, R6 and the forthcoming R7, points out that while the 600’s chassis, brakes and engine were designed with racing in mind, such things as its Rl-inspired riding position, suspension calibration and generously padded seat are geared for the street.

Yamaha’s new middleweight was introduced to the world’s press in Melbourne, Australia, with a street ride followed by a day at the Phillip Island racetrack, home of the Australian Grand Prix. The festivities began with a brief bus ride to a local airfield. There, we boarded a Piper Chiefton twin-engine turbo prop, the tattered interior of which resembled a ’60s-era VW microbus. To make matters worse, the plane’s bush pilot was the spitting image of Carl Fogarty! Adding to the concern of my compatriots was the fact that I strapped into the small plane’s last available seat-the one to “Foggy’s” immediate right. “Uh, welcome aboard, I’ll be your co-pilot on today’s flight...” Qantas Airlines it wasn’t.

A turbulent hop along Australia’s southern coast provided a bird’s-eye view of The Great Ocean Road, our planned route. We landed at a rustic dirt airstrip near the town of Geelong, where a couple dozen R6s awaited, neatly lined up in front of a hangar.

Tracing the rugged shoreline, the scenic road’s grippy surface and wide mix of comers was enticing. But long strings of slow-moving Sunday tourist traffic and the imminent threat of a $1200 (yes, really!) speed violation was enough to impede my progress. So drone I did.

Apart from a brief period of numb-wrist syndrome after 45 minutes of fairly comer-free cruising, I found the R6’s comfort quotient perfectly acceptable. Engine vibration is mild, although a light buzz seeps through the bars at all rpm. Plugging along Aussie roadways at 60 mph registered 5000 rpm on the tach, with enough Fosters on tap to easily pull a top-gear pass. Power delivery remains relatively mellow when the rev-happy motor is short-shifted below 8000. That’s right: 8K can be considered midrange when the engine’s redline is set at a stratospheric 15,500 rpm, as is the R6’s.

Power delivery is multi-stepped, with pronounced gains felt at 6, 8 and 10,000 rpm when gassing it hard in lower gears. Nailing the throttle in first gear snaps the R6 into a full wheelstand, while rolling it open at low revs produces a progressive wheelie as the tach sweeps past 8000. Racers and road warriors in a hurry will want to keep the engine spinning between 10,000 and 14,000. The excitement of high-rpm operation is an essential element in the R6 riding experience. In fact, Mr. Miwa-a former GP roadracing engineer-says that an intentional torque dip was designed into the lower rev range to give the R6 an exhilarating, twostroke-style rush of top-end power.

Lessons learned in GP racing also have been applied to the R6’s chassis, which employs an extra-long, truss-type swingarm. As with the Rl, the R6 has vertically stacked gearbox shafts that significantly reduce front-to-back engine dimensions. The engine’s compact size has allowed it to be better positioned in the Deltabox II frame for correct weight

+distribution, which affects both handling and tire grip. While the R6 proved to be a light-footed and stable dance partner on the street, hot laps around Phillip Island were required to approach the bike’s true potential.

Intermittent rain showers punctuated our track day, giving a good dose of full-tilt cornering when dry combined with an appreciation for the bike’s controllability on a wet surface. Phillip Island offers everything from tripledigit sweepers to a pair of second-gear hairpins, along with a few elevation and mid-comer camber changes thrown in for good measure. While the track’s surface is for the most part smooth, a few corners had bumps or ripples near the apex. Yamaha factory rider Rich Oliver was also on hand to show us the fast line around the track.

Ridden at a moderate pace, the R6 remained extremely planted at all times. As the lap times dropped, however, the front end occasionally felt light, even while rocketing down the front straight with the digital speedometer showing 165 mph. A hint of handlebar shimmy I experienced over bumps through the track’s fastest bend, a left-hander taken at full lean at an indicated 140 mph, got my attention.

Shifting my body weight forward helped some, as did reducing rebound damping at both ends. Spring preload, compression and rebound adjusters are present on both the fork and remote-reservoir shock. The range of adjustability should serve well for most street riders and club-level roadracers.

Cornering clearance seemed nearly limitless, though the bike I rode was fitted with European-spec street-compound Bridgestone BT56 radiais; Stateside R6s will wear Dunlop D207s. The Bridgestones provided neutral steering and offered fairly impressive grip. While the 295mm front brake rotors and one-piece four-pot calipers are the same components found on the Rl, a different pad compound is used to better suit the R6. Heavy use of the brakes never caused the stout, 43mm conventional cartridge fork to bottom or the wheels to get out of line with one another.

In contrast to the typically refined Honda CBR600F4, the R6 offers a more exhilarating yet demanding ride.

With the FZR600 and YZF600R remaining in Yamaha’s ’99 lineup as its “entry-level” 600s, the R6 is free to cater to the skilled sport rider.

Yamaha and Mr. Miwa have rewritten the rules yet again. First, they gave us the Rl with its Open-class motor shoehorned into a 600-sized chassis. Now, the YZF-R6 has redefined what a 600-sized chassis can be, while its engine performance runs deep into the 750cc class. Could a production street version of the YZF-R7 unveiled at the recent Munich Show be in the works? It may be necessary, if only to maintain the traditional balance of power. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGeneral Stupidity

January 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsPaperweights of the Gods

January 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHot Oil Massage

January 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1999 -

Roundup

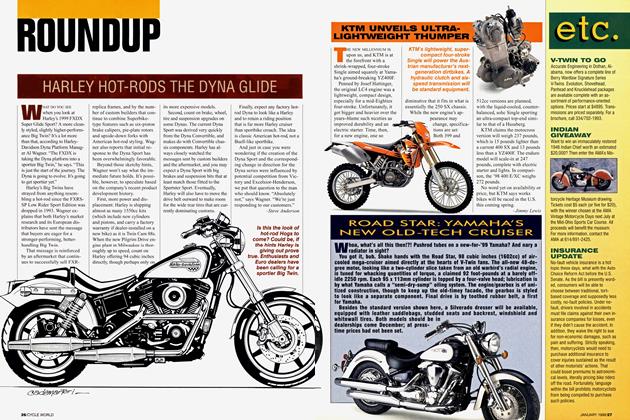

RoundupHarley Hot-Rods the Dyna Glide

January 1999 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

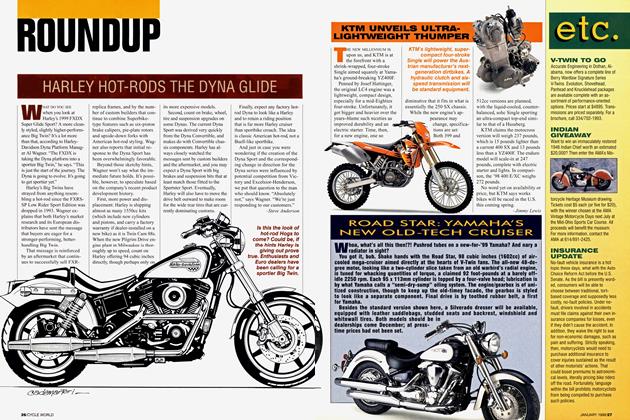

RoundupKtm Unveils Ultralightweight Thumper

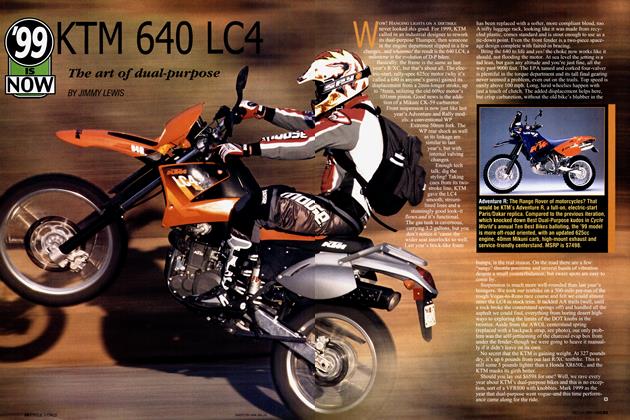

January 1999 By Jimmy Lewis