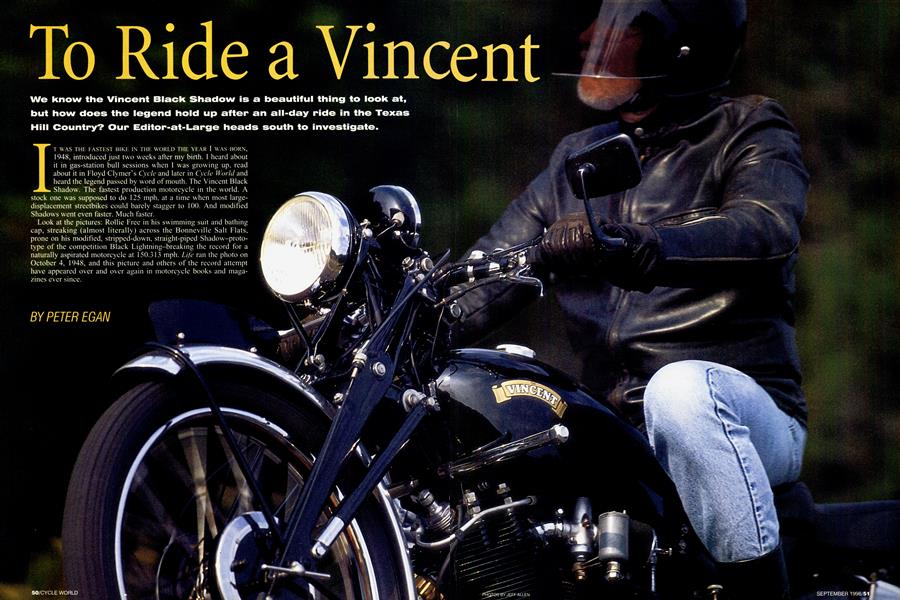

To Ride a Vincent

We know the Vincent Black Shadow is a beautiful thing to look at, but how does the legend hold up after an all-day ride in the Texas Hill Country? Our Editor-at-Large heads south to investigate.

IT WAS THE FASTEST BIKE IN THE WORLD THE YEAR I WAS BORN, 1948, introduced just two weeks after my birth. I heard about it in gas-station bull sessions when I was growing up, read about it in Floyd Clymer's Cycle and later in Cycle World and heard the legend passed by word of mouth. The Vincent Black Shadow. The fastest production motorcycle in the world. A stock one was supposed to do 125 mph, at a time when most largedisplacement streetbikes could barely stagger to 100. And modified Shadows went even faster. Much faster.

Look at the pictures: Rollie Free in his swimming suit and bathing cap, streaking (almost literally) across the Bonneville Salt Flats. prone on his modified, stripped-down, straight-piped Shadow-proto type of the competition Black Lightning-breaking the record for a naturally aspirated motorcycle at I 50.3 1 3 mph. Lifr ran the photo on October 4. 1 948, and this picture and others of the record attempt have appeared over and over again in motorcycle books and maga zines ever since.

PETER EGAN

"That engine was put into the frame with a whip and a chair," someone wrote, and the phrase stuck in everybody's mind. A sinis ter-looking black bike full of exter nal plumbing and raised oil lines standing out from those early B-Series engine cases like veins in a bat wing. The Black Shadow. When I was a kid it sounded menacing, like a combination of black widow spider and masked movie matinee phantom, everything exciting and dangerous packed into one machine.

I grew up trucking all this lore around in my small, young brain. The Vincent as ultimate.

So naturally, I have lusted after Vincents these many years, both in heart and mind. I have gradually accumulated a small library of books and magazines on this illustrious marque, whose history stretches from 1927, when Philip Vincent bought the respected but insolvent HRD motorcycle company, until another insolvency closed the factory in 1955. The bikes I like best, the 1000cc V-Twin Series B and C Rapides and Shadows, were all made after WWII.

The Rapide was the "regular" version, the Black Shadow the high-performance model, hot-rodded with higher-com pression pistons, bigger Amal carbs and hand-polished inter nals, good for a whopping 55 bhp-lO more than the Rapide. It also had fins on its dual 7-inch front brake drums, and, of course, black-enameled engine cases and cylinders.

The Rapide is, perhaps, more beautiful with its polished aluminum cases, while the Shadow is...well, more legendary and even more romantic, if that's possible. Also about $10,000 more expensive, these days.

But I have not bought either one.

And why not?

Well, as I mentioned in a recent column, these bikes have always stayed just ahead of my income and/or frivolity level, much like the carrot on the stick dangled in front of the don key. When Vincents were $5000 back in the early Eighties, you could bny a brand-new 900SS Ducati for that. Now Vincents are anywhere from $15,000 to $35,000, depending upon model, history and condition, and you can buy a Ducati 916, slightly used, for $14,000. You see the problem.

Ut none of this has stopped me from wanting one. I mentioned this life-long fascination to Editor David Edwards over dinner at Daytona this year (while showing him J.P. Bickerstaffis new book, Original Vincent Motorcycle, which now goes

everywhere in my luggage or under my arm) and he asked, "Have you ever ridden one?"

"Yes," I replied. "Jay Leno kindly let me ride his Vincent Rapide about 10 years ago. We went to breakfast, riding up a winding canyon in the Hollywood hills to a cafe. It was a great experience, but we didn't really get out on the high way. I guess before I sell everything I own and shell out $15,000-plus for a motorcycle, I'd like to ride one for a full day on the road, spend a few hundred miles in the saddle."

David raised one eyebrow and said, "You know, I'll bet that could be arranged. We just did a story on the Rollie Free speed-record bike ("Return of a Warhorse," CW, January); it belongs to an avid Vincent collector named Herb Harris, in Austin, Texas. Herb has several Vincents, including a Shadow he rides on the street. He said if we ever wanted to come down to Texas and take a long ride out into the Hill Country, he'd love to have us visit."

I looked at David and grinned like a person showing off a new set of extremely white teeth.

"I'll call Herb and ask if we can do it. Probably have to wait until spring, when it's a little warmer and the bluebells are blooming in the Hill Country."

God, I love this job.

Austin, Texas, the green Hill Country and Vincents Three of my favonte things and places on Earth, all in one trip As Jelly-Roll Morton used to shout while banging away on the piano, "Somebody shoot me while I'm happy!"

Nobody did, so a few months later my plane landed on a hot, sultry late-spring day in Austin, where I was met at the airport by a cheerful Herb Harris and his good friend and Vincent co-restorer, Stan Gillis. Herb owns a law firm in Austin, and Stan is a former Dallas banker who gave it up to restore motorcycles and work part-time for the law firm. CW photographer Jeff Allen flew in from California, we checked into a nearby hotel and then drove to Herb's home in suburban Austin for a look at the bikes.

Herb has a nice brick home that is my idea of perfection-large garage and six motorcycles parked in the living room: three Vincents, a BSA Gold Star and a Manx Norton, a testament to the good nature of his wife Karen. The Rollie Free bike was being shown in England, but Herb has another famous rac ing Vincent in the living room, the 1949 Reg Dearden Lightning, converted at the factory to use a Shorrock super charger. I told Herb that if I had this room in my house, I would never go to bed. I'd just sit up all night long with a drink and look around.

The garage collection is not bad, either. Out there, he has a BMW R100RT, a 1927 Brough Superior 680, an immacu late 1965 Triumph Bonneville, an unrestored-looking 1936 Vincent HRD Comet Special 500 and-the object of our trip-a 1951 Series C Black Shadow, flawlessly restored.

And what a sight. All engine, set off with glistening black paint, gold-leaf trim and stainless steel.

Philip Vincent and head engineer Phil Irving ("the two Phils") designed these bikes to use the engine as a stressed member. Like a modern Ducati 900SS, the triangulated swingarm pivots on huge bearings in the back of the uni tized engine and transmission cases. Dual spring boxes and single hydraulic shock are up under the seat, where they push against the "UFM," or upper frame member. This is nothing but a long rectangular box that serves as the oil tank, bolted securely to the cylinder heads. There are also two friction dampers, tightenable with lovely knobs, attached to the seat stays.

The steering head bolts to the front of the UFM. Front forks are girder type "Girdraulics" with long spring boxes behind them and a single hydraulic shock behind the headlight.

In other words, you essentially have the front and rear sus pension bolted to a great big V-Twin engine, with a little help from the oil tank. Add seat and gas tank, and there's your bike. Brilliant and simple.

But the mechanical detail of the bike is anything but sim ple. The two Phils made everything adjustable-or "infinitely maladjustable," as Stan points out. There are tommybars and knobs everywhere. Wheels can be removed, like those of a racing bicycle, without tools, and all the footrests and levers can be adjusted to fit the rider or passenger.

The engine itself is notable for several innovations. It had a) unit construction when most bikes did not and b) rocker shafts that operate on collars on the centers of the valve stems, rather than on top, with separate upper and lower valve guides. This allows shorter pushrods for less recipro cating weight, shortens overall engine height and keeps the valve springs high and cool in the heads. It also lowers the rocking friction of the valves against their guides.

Vincent called this a "semi-overhead cam" engine, which is something of a stretch, as a thing is either overhead or it isn't, and these aren't. But it's a clever design.

The angle between the cylinders is 50 degrees, and the heads are hemispherical, with two valves each. A magneto handles the sparks and a Miller generator the lighting current. And above the headlight sits one of the most famous talis mans in all of motorcycling, the gigantic 5-inch "Shadow clock," a 150-mph Smiths speedometer made especially for the Black Shadow. It's the size of a saucepan-which, in fact, was exactly what the early speedos were made from. Cookwear never looked so good. Or went so fast.

I ask Herb if the bike needed much work when he bought it. He nods wearily: "The engine had supposedly been `profes sionally rebuilt,' but it had many latent problems and needed

to be rebuilt from the crankpin out. We sent it out to Dick Busby, a Vincent specialist in Culver City, California, who does all our engine work now, working with Haig Altounian. Mike Parti did the crank. We started calling Busby `Bad News Dick,' because every time he called he had bad news about the engine: `Your timing gears look like they've been under water for three years!' That kind of thing."

Gradually, it got done, though. The tank was repainted by Wayne Griffith in Los Angeles, and the original "loaf of bread" seat was restored to neat tautness by Michael Maestas in Sylmar, California. Herb and Stan did most of the assembly.

The Shadow, Herb says, was originally sold to Indian Sales Corp., USA (chassis number 5708), shipped in December of 1950 and sold in 1951. Its ownership lineage was lost after that, but Herb bought it in 1995 from a collec tor in Dallas. "He got rid of it when it spit him off," Herb says. "He went through a puddle that turned out to be more than a puddle. It was three feet deep. The bike somersaulted and bent the front wheel, but there was no other real dam age. Those forks are made of forged-aluminum alloy, manu factured for Vincent by the Bristol Aircraft Company, and they are extremely strong."

"We restored it to pretty original and stock specifica tions," Stan says, adding that the only non-standard touches are 8.5:1 "Kempalloid" pistons, replacing the original 7.3:1 pistons, and a 21-inch front tire from a Lightning rather than the stock 20-incher. Also, it has a Ducati 900SS dry clutch, from the current generation.

I pull in the lever, which feels about like my Ducati's. "Is this an easier clutch to operate?" I ask. - - -

"No, the stock one actually has a lighter pull and is nicer to use, but the Ducati clutch is easier to clean if the engine breathes oil on it through the bearing seals, which occasion ally happens," explains Stan.

So. Riding would come in the morning, but first dinner.

erb and Stan took us out to the Oasis, a great Tex-Mex restaurant built on a series of porches overlooking Lake Travis, like a big treehouse 1000 feet above the lake. Over dinner, I learned that Stan and Herb have been riding since high

school and, between them, have owned, restored, broken or patched up just about every motorcycle ever made: BMWs, BSAs, Ducatis, Harleys, Hondas, Kawasakis, Laverdas, Nortons, Triumphs, etc. Motorcycle guys of wide focus, lifelong and hopeless, which we now know to be the best kind of person. They've got the disease.

In the morning we had a Mexican breakfast at the famous Cisco's Cafe in east Austin, under paintings of Willie Nelson and Texas humorist Hondo Crouch, of

Luckenbach fame, then headed back to Herb's garage.

I put on my jacket, got my helmet ready and Herb gave me the cold-starting drill:

1. Turn on fuel tap-or both of them, if you plan to go 70 mph or more.

2. Tickle front carb float chamber for 3 seconds.

3. Tickle rear chamber briefly, just until it admits fuel.

4. Kick engine over with compression release in.

5. Say small prayer.

6. Pull in compression release and kick firmly, releasing lever halfway through stroke.

7. Repeat again and again. (The bike tries to start on first kick, and actually lights off and runs on Herb's fourth kick.)

8. Open oil cap in center of tank and see that oil is return ing. If it is, you are ready to ride.

Herb warns me it takes a while-at least 15 miles of riding-for the engine oil to be really warm, so the first few miles should be moderate.

I straddle the Shadow and listen to the engine's deep, steady idle. It's remarkably free of rattles and gear noise, yet I have read that Vincent Twins normally sound like "a gas stove being dragged over cobblestones" at idle.

"They all come out different," Stan tells me, "no matter how you build them. This one is quiet. Dick did a nice job, shimming everything."

I pull in the Ducati dry clutch (which, inexplicably, doesn't rattle as it does on my 900SS), click the right-side gear lever firmly up for the first of four gears in the famous ly stout Vincent-made box and we are off. Herb is leading on his BMW R100RT, and Jeff, Stan and Herb's son Brian follow us in a mini-van.

As soon as we are rolling on the highway, memories of Leno's bike come back to me. You sit close to the tank on the Vincent, with a short reach to the semi-flat bars. The bars, pegs and controls are set-up for Herb, who is 6-foot-4, but they fit me (6'!") exactly right. This is just abOut the ideal sport-riding position for me, similar in layout to a 400F Honda or Ducati Monster. It is what I call the "alert Airedale" riding position-canted forward slightly onto mod erately narrow, flat bars, feet just slightly back, head up.

A car pulls out on the highway in front of us and I get my first real surprise from the Vincent: The brakes work. Light, two-fingered pressure on the front lever hauls it down fast from 70 to 45 mph, though the rear drum is only fair. The front brakes feel almost modern, unless you have a really long, howling stop on the high way, and then they begin to fade a bit at the very end of the stop. In any case, they are vastly better than any of the mid-Sixties drum-braked Triumphs I've owned.

Handling, too, is surprisingly modern: Quick in slow corners, with a very slight ten dency to fall into really slow turns (just above walking speed, as in a parking lot), and dead stable in fast sweepers, without a sign of headshake or fork deflection over bumps.

The bike loves to tick along at 70-80 mph in an effortless all-day canter. I've heard so much about Vincents with a "hinge in the middle" that I'm ready for anything, but there's no hinge anywhere on this bike. It's solid as a brick, unfazed by switchbacks, dips, roller-coaster hilltops, fast sweepers or bumpy mid-speed corners. Not a bobble all day, and this is surprise number two. It is, honest ly, one of the nicest-handling bikes I've ridden, neutral and instinctive on turn-in and lean. Grip is good, too, with the 21-inch Avon Speedmaster II front and 19-inch Avon Super Venom rear tires.

In both acceleration and handling, it's eerily close to the 1979 Guzzi 1000SP I recently bought, but lighter on the bars and a little more exciting and sharp in its upper-end rush. The road-feel also reminds me somewhat of a Ducati 750GT; it's got that same easy gait, but with a shorter and more nimble chassis. Performance is far from eyeball-flat tening, but the engine pulls hard from almost any rpm and builds speed quickly. There's no tach, and little temptation to buzz the muscular Twin-peak power occurs at 5700 rpm-even though it's quite smooth at the upper end.

Sound from the engine is a rich, full thunder, but mellow and never headache-loud. It's a lot quieter than the twin Contis on my old bevel-drive 900SS Ducati. The exhaust note is satisfying, but not quite comparable to anything else. You can't say it's like a Harley or a Ducati; as Stan says, it just sounds like a Vincent.

e stop at the little village of Driftwood to pose the bike in front of an old general store that is now a working silversmith's shop. Texas flag flying, old gas pump out front. I lean on a porch pillar to get my picture

taken next to the bike and say, "How is a Vincent owner supposed to stand?"

Herb shouts, "Look superior!"

Next we head for Lime Creek Road, Austin's version of the Angeles Crest Highway, a wonderful winding river road full of dips, ess-bends and whoop-dee-doo rises. Great fun. The Vincent actually runs up the back of the BMW in many corners, even though Herb is riding fast and smoothly. The Vincent is simply lighter, lower and easier to manage. It doesn't have to be wrestled as much as the tall, fairing equipped BMW.

Ride? The forks and rear suspension are remarkably sup ple over small bumps, but they can deliver a pretty good jolt to the spine in a large dip or pothole because there's not much travel. Over the rough stuff, you learn to ride in the equestrian mode, standing up slightly in the stirrups and light in the saddle.

Vincent and Irving hated tele scopic forks because of their inherent stiction and brake dive, and insisted on girder forks after most others had abandoned them. On these roads, the men are largely vindicated in their shared opinion. Only the most recent telescopic forks (and BMW's Telelever suspension) feel as responsive over minor, pattering bumps or as settled under braking.

We turn out onto a long, empty stretch of road and Herb hustles the BMW up to about 80 mph. I stay with him easily on the Vincent and then decide to open it up and pass. I hammer forward to 95 mph and breeze past, still accelerat ing steadily before I have to shut it off for a blind hill. There's lots left at 95, but I decide that's fast enough on a hot Texas afternoon (102 degrees) with a 47-year-old British classic that doesn't belong to me.

Herb is laughing when we stop at a gas station for cold drinks. "What a wonderful sound that thing makes going by at speed! I never get to hear it from another bike!"

It amazes me how easy the Vincent is to ride in the compa ny of a relatively modern, big-bore motorcycle. Other than high maintenance and the archaic (but useful) rear stand, there's no real penalty for the bike's 50-year-old design.

Over lunch (okay, candy bars and Gatorade) I tell Herb and Stan I've been reading for years what evil handlers Vincents are supposed to be, how non-existent their brakes, how disap pointing their supposedly legendary performance, etc. It's become practically a journalistic convention to ride Vincents

and then try to take them down a notch, to destroy the myth. "It's obviously not a Honda CBR900RR or a Yamaha Ri in performance, but it's certainly a magnificent bike by any stan dard," says Stan. "And, for its age, it's spectacular."

"A lot of people want to hate Vincents," Herb says. "In fact they love to hate Vincents. I guess the bikes were on a pedestal for so long, and so few people actually owned and rode them, that it was comforting to believe they weren't all that good."

"You have to remember, too," Stan adds, "that the Vincent is a very complex bike, and if you work on one and don't know what you're doing, you can really mess it up. A badly assembled Vincent is a disaster."

"Handling is absolutely no problem," Herb says, "if the swingarm preload is correct and you keep the tire pressures right. Also, you can't have the front end adjusted to its side car position, which a surprising number of people have done by accident. You have to get everything right, and then they're really nice to ride."

Stan grins and adds, "We've developed a saying while restoring Vincents: `These bikes are monuments to unlimit ed funds, talent and perseverance.' You can get them right, but it does take dedication."

t the end of the day, when we rumble back into Herb's driveway, we've covered just over 200 miles of hard riding on a very hot day. In that time, the only problem was a shift lever that loosened slightly on its shaft, and that was quickly snugged up with a wrench. Also, the clutch got just a bit grabby when I turned around (over and over again) in the road for photos. I killed the engine twice while maneuver ing, but both times started it with a single kick. Otherwise, the bike had been flawless.

Back in the dark air-conditioned coolness of Herb's living room/museum, we finish off the afternoon talking about the bikes. I put a question to Herb, one that has been much on my mind.

"It seems to me there are an awful lot of disaster stories out there about Vincents with engine trouble, like the prob lems your own bike had when you bought it. We know that Vincents are great motorcycles, in the sense of being leg endary, but do you think they are good motorcycles? Are they honest?"

Herb nods, as if he's heard the question before.

"1 think they are. The Vincent repays your efforts, and that makes it honest. And I like the special reward that comes from owning such a bike. Vincent achieved great things; it was on the absolute edge of the performance enve lope, the highest performance of the post-war era.

"Also," he adds, "the materials used throughout the bike are absolutely first-rate. They used the best of everything they could find and cut no corners on quality. Every piece on the bike is nicely designed and beautifully made out of sunerior materials." ___________________-

"No disillusionment after restoring these Vincents?"

Herb Harris smiles and shakes his head. "No. I'm always testing ro mance against the reality with motorcycles, and with Vincents the spell has not been broken." Nor for me. I still want one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

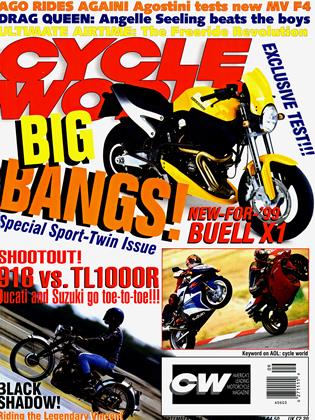

Up FrontGood News And Bad

September 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsPassing Temptations

September 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTrouble With Turbines

September 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1998 -

Roundup

RoundupBig-Bore Hornet Set To String

September 1998 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupNew For '99: Dirt

September 1998 By Jimmy Lewis