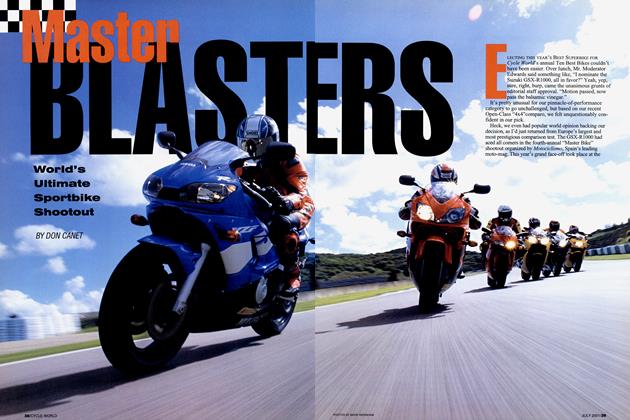

WFO, Mate!

How an English rowdy taught Americans to go fast

JOE SCALZO

I READ CYCLE NEWS NOT SO MUCH FOR ITS HOT NEWS AS FOR ITS GEEZER ITEMS: Every week I breathlessly consult "In The Wind," the gossip page, to discover what the old berserkos and hairpins of my generation are up to, who has divorced who this time, who has been overthrown and run out of office, who has gotten creamed playing vintage racer, or who has completely cracked up in his dotage and done something so disgraceful that he has been sent to the jug.

Or who has stepped off. In that extreme regard, in CN's number of January 11, 1995, I read: "Former Suzuki factory roadracer Ron Grant, 54, was killed in a boat ing accident on Wednesday, December 28, in Northern Ireland. Grant, an Englishman who first moved to the US. to race in 1962 before moving on to New Zealand and then back to England, was one of three men killed in the accident which took place in rough seas on Strangford Lough, south of Belfast..."

I dug through my files to unearth an ancient magazine with a photograph of the deceased. Taken at the Anglo-American Match Races of 1972, the photo shows Cal Raybom, Don Emde and Dick Mann on one end of the picture, and Jody Nicholas, Art Baumann and Grant on the other. Only one member of the sextet is mugging for the camera: Grant.

You fantastic maniac, I thought, whatever were you doing in a freakin' canoe!?!

Ron Grant was a monster roadracer, one of the fastest of the 1960s and 1970s, and there are never enough of them. We should give thanks to every champion like Grant who can raise our spirits pulling off fiendishly difficult feats of derring-do without eating it. Parlaying smoothness with mad-dog speed, Grant was amazing to watch. Never was he a wobbler or a crasher.

But! Out of the saddle and not behind the streamline of a hellbent crotch rocket, Grant was almost certifiable, a won drously crazy dingbat. He always lived beyond his means and piggybacked from debt to debt. He had businesses cap size into foreclosure, homes disappear, automobiles repos sessed, and during one especially Looney-Tunes afternoon at Willow Springs Raceway, gendarmes arrived and impounded Grant's Manx Norton right on the starting line.

He once sank a foreign-car dealership, and another time flew the coop leaving investors holding the sack for a bal loon payment of $50,000. He whacked his friends just as hard. Some of those who worked for Ron never quite fath omed how at the end of a work week they ended up owing him money. And friends who attended the going-away-to New Zealand party that Ron threw for himself were dis tressed to learn after the host had left the country that they were obligated to pay for the soiree.

Ron Grant was a full-on racer and a jolly bloke, but he did horrible and dumb things that on occasion threatened to put him behind bars. God knows it would have been deserved.

Do you follow me? Ron Grant was a full-on racer and a jolly bloke, but he did horrible and dumb things that on occasion threatened to put him behind bars. God knows it would have been deserved. And yet, with the possible exception of a couple of ex-wives or creditors that he really soaked, everyone was deeply moved by his death. I don't know anybody who didn't mourn him.

The explanation, of course, was that diehard racers, the dudes who were the genuine arti cles, used to seldom make good 9-to-5 tax payers. Much like painters and poets and other artists/adventurers, there was always trouble with them. They were unreliable. They misbehaved and raised hell and enjoyed life too much, and without guilt. They weren't like the rest of us stiffs-how could they be, doing the things they did? So, we forgave and forgot and cut them lots of slack.

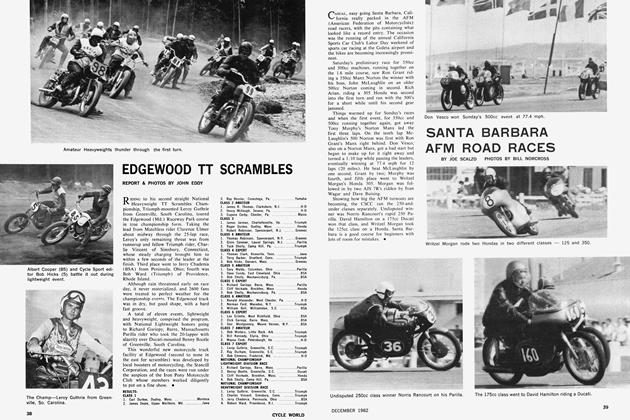

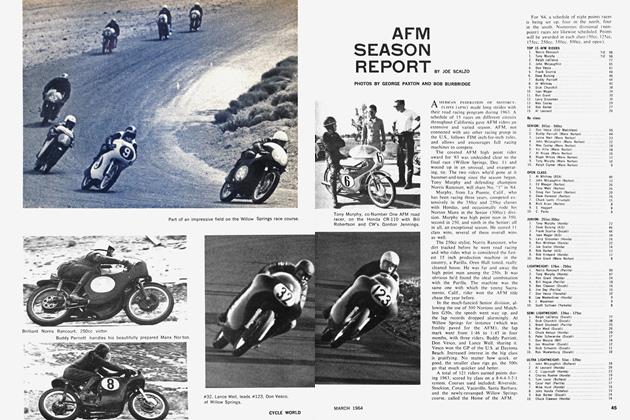

I could blow smoke and pass myself off as a Grant authori ty, but the only time I ever saw him regularly was through the middle 1960s. Somewhat like a UFO, he dropped in on the American Federation of Motorcyclists, Los Angeles wing. Us AFMers were a ragged body of amateur roadracers. We. had our Manx Nortons and Matchless G50s and AJS 7R Boy Racers and Harmon-Collins cammed-and-kitted Honda 305 hot-rods. We scarfed down the aroma of Castrol R and dug the trusty grip of Dunlop "Green Spot" rubber. And we play-raced at Willow Springs in the Mojave with its sage brush and tumbleweeds right up to the pavement, or at Riverside International Raceway which could be rented out during the week for 10 clams a day. We had it made.

Unfortunately, the more ambitious among us had guilt pangs out the kazoo. There we were, living in free-wheeling L.A., mingling with all the other Beautiful People in the sun shine 240 days a year, but inwardly knowing that in order to become echt racers we should be suffering in the rain and misery of the U.K., making our bones at Brands and Mallory, plus facing catastrophe hurtling around the Isle of Man's 37 miles of unbroken stone walls, curbs and mountains.

So, suddenly one day in 1962 this Ron Grant arrives among us-Hello, mates!-and none of us were ever quite the same.

Grant was formidably resplendent in his form-fitting Lewis leathers, puddin' bowl Cromwell helmet with checkeredflag-and-Union-Jack logo, and flyweight zippered booties bearing unmistakable wear-and-tear scars from the mighty Island herself. And right away he drove us nuts telling truelife stories about making the turn at Creg-ny-Baa in the fog and about ear-holing with Mike the Bike and Phil Read.

He wanted to help us, and in no time had shaped up a bunch of spaz wannabes into real asphalt terrors who, if we gritted our teeth and did just what Ron said, truly could run the hellish curves of the Riverside esses full-bore: "Mates, you'll blow those other wankers into the weeds if you do," he instructed, and he was right.

We elected him to our board of directors; watched him win most of our races and trophies. I don't believe any of us ever understood how Ron, whose sole source of income was from a mechanic's gig in a modest Honda shack, was able to

tool around in an Aston-Martin, and it didn't matter. But now, all these years later, I can reveal without being critical that his modus operandi was rudimentary: He simply bought things and didn't pay for them.

Not long after his L.A. arrival, some Florida chick he was on the lam from had him put in jail. It seemed that Grant, the cad, had met her at Daytona's U.S. Grand Prix on a Thursday, married her on a Friday, then ditched her the fol lowing Monday. Or something like that. He did get out of the slammer, but barely skirted deportation.

Next, he fell madly in love with Barbara Flack, whom he'd met at a local AFM meet but who lived in Sacramento, 400 miles north. Because of the distance separating them, a lot of their courtship was conducted via long-dis tance telephone. Or it was until the phone company, tiring of Grant's refusal to pay three months of bills, churlishly removed his apartment service and replaced it with a pay phone. Grant knew a thing or two about petty criminality and hot-wired the lines. This time, the telephone people didn't dick around. Agents came out to the apartment, jerked the pay phone right off the wall, and Ron was left with no way to communicate with Barbara whatsoever.

Almost 30 years ago, those flexi-flyer Suzukis were travel ing a mind-warping 170 mph, at which point they out ran their tires and started shredding them. Have mercy!

Which meant that Ron, if he were to continue wooing, had to do it on weekends by rocketing automobile. Bill collectors had taken away his Aston, but he'd acquired a used Mercury off an iron lot. It was in decent shape when he got it, but a merciless diet of 800-mile round-trip runs with the hammer down steadily reduced it to a weeping, dying junker. He was constantly soliciting company for his L.A.-to-Sacramento

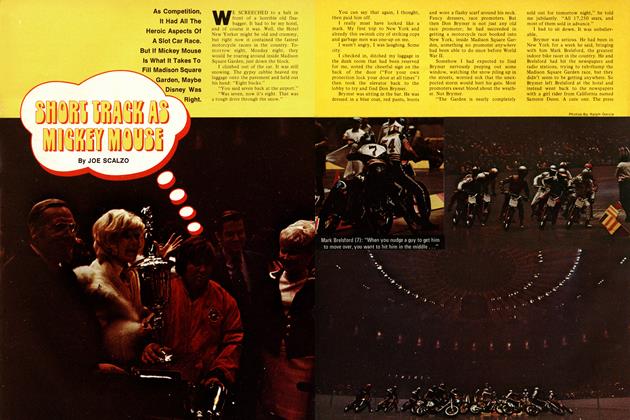

and-return odysseys; he wanted an extra pair of eyes peeled for the fizz, as well as some sucker who would drive home on Sunday nights while he dozed in the back seat. Which was where I came in, particurly after a blind date was pro cured for me while we were in Sacramento. So, early one Saturday he kicked in the Mercury's weak ening afterburners and catapulted us north, reaffirming there would be no dragging our asses: "Right! No coffee breaks, no stopping to have a pee, just WFO, mate!"

We roared across the San Joaquin Valley with the speedo pegged and the Merc belly down with all rods knocking. Before finally pulling us over, a county mounty (whom we'd earlier blown off) had to chase us Code Three for five miles. Or so he lectured, gleefully preparing to lay Grant the mother of all speeding citations.

Diehard racers used to regularly stumble into dire brushes with the law-it was just another part of their deal-and then creatively extricate themselves. One A.J. Foyt Jr., for exam ple, an Indianapolis 500 wheelman of a certain fame, includ ed in his memoirs an interesting account of a high-speed motor trip he once made in the company of Linda Vaughn, Miss Hurst Golden Shifter. Exactly like Grant and myself, they'd gotten nailed by the heat. And Foyt surely would have been for it if he hadn't had the bold inspiration of cut ting a fast quid pro quo with the horny speed cop who'd captured him: In exchange for Linda flashing her worldclass gazongas, A.J. escaped a brutal ticketing.

Grant, too, had the balls and imagination to talk himself out of disastrous and unlawful situations. And without whimper ing for mercy, either. I groaned when I heard him addressing the cop in that upper-class accent that Brits automatically shift into when they're trying to slip something past yoke Yanks. But my groan turned to admiration when Grant whipped out his U.K. driver's license and invented a corny cock-and-bull fable about not knowing kilometers from miles per hour, and honestly mistaking "99" for a boulevard speed limit instead of the name of the highway. No ticket! We arrived in Sacramento, and Barbara was waiting for us with my date. She was cute, and when we adjourned to a drive-in movie I anticipated an evening of fogging up the car windows. But Grant got restless. He fired up the Mercury and bayed at me that we were out of there and to ditch the drive-in speaker. Before I could, we went screeching off in low gear. I was jerked halfway out the window before the cheap electri cal cord extended and snapped, then was flung back into the car all over again still clutching the speaker. Fiercely picking up speed, we fled the drive-in, night motocrossing as the moaning Mcrc smashed, sparked, careened and became air borne yo-yoing over the speed bumps.

Ron and Barbara got hitched shortly afterward, and it last ed for 13 years-the longest of any of Grant's three or four marriages, including the Florida debacle. I think they were very happy together. Ron continued getting into messes, rac ing and financial alike, and Barbara helped clean them up.

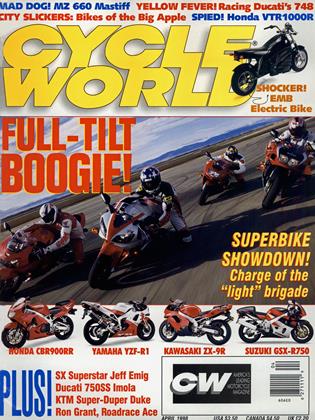

After that, I sort of lost track of him. But for Grant, everything accelerated violently in 1965 when he took in the Daytona 200 for the first time, plus other AMA road extrava ganzas. His joining the AMA required more nerve than you'd imagine, because the AMA's pavement gang in the 1960s was made up of hardcases who in the main assumed that a pretty-boy Brit who didn't race with high bars had to be a wuss. By tradition, the fastest elements of the AMA (Dick Hammer, Gary Nixon) were also the maddest. And-birds of a feather!-how delighted Hammer and Nixon were to discover that Ron was even worse than they were. Accounts of the trio's off-track hijinks together are part of 1960s' mythology.

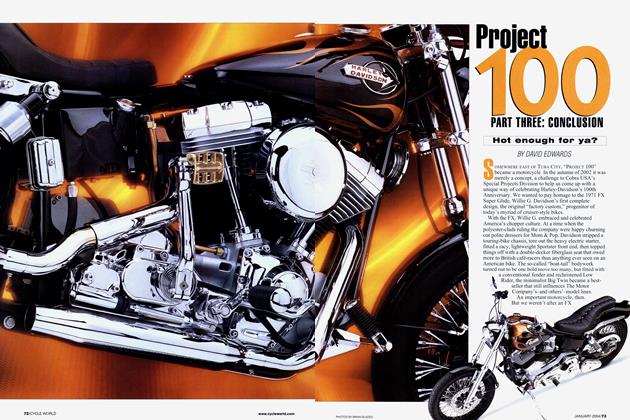

In the 1970s, Grant the expat Bnt, and Kel Carruthers the expat Aussie, and Yvon Duhamel the French-Canadian, all demonstrated to domestic roadracers how to milk Japanese manufacturers Suzuki, Yamaha and Kawasaki for big bread. Ironically, however much jack Grant got from Suzuki to ride its killer-diller three-cylinder 750s, he was drastically under-

paid. Those things were unguided missiles-you had to be twisted just to want to go near one. Almost 30 years ago, those flexi-flyer Suzukis were traveling a mind-warping 170 mph, at which point they outran their tires and started shredding them. Have mercy! The reflexes, cojones and raw talent required to go fast and stay aboard without getting spit off was unimagin able but, better than both his teammates, Ron managed it.

Before getting out of racing in the middle Seventies, Grant won the Kent National of 1970 and came close to winning two bitterly hard-fought Daytona 200s. But to me, his great est moment as a racer came in 1973, in New Zealand during the same dangerous wintertime tournament that snuffed Cal Rayborn. At Wanganui Cemetery and Wanneroo Park, two between-the-buildings road circuits with lethally narrow cor ners and no margin for error, Grant and his overpowered Suzuki utterly demolished fields of international riders on far more maneuverable motorcycles. For some reason, these exploits never got the ink of, say, Kenny Roberts taming his runaway Yamaha TZ on the Indianapolis Mile, but they were equivalent acts of brilliant riding magic.

Diehard racers can't all be expected to expire in bed, but of all the old bizarros, Ron Grant was the one I half-expect ed to live forever-which was why the shock of reading his obit made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. He'd bested devil-bike Suzukis, spurned spouses and angry credi tors, and even disintegrating Mercurys. What could harm him after all that?

Matey, you were beautiful!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue