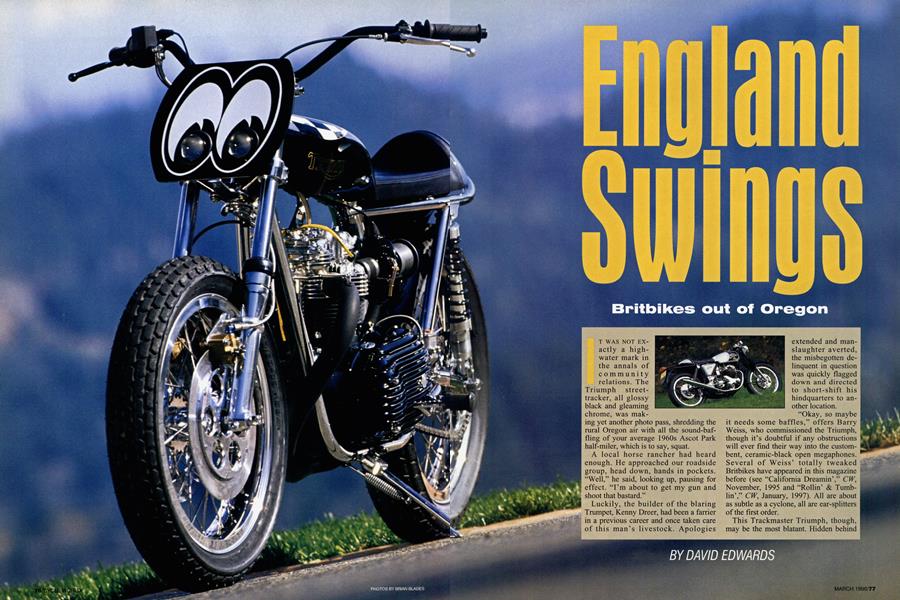

England Swings

Britbikes out of Oregon

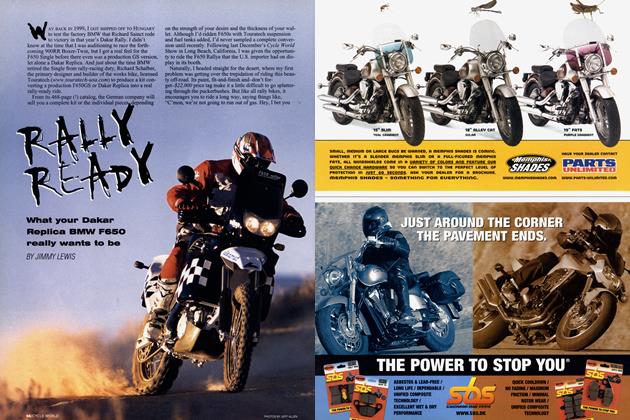

IT WAS NOT EXactly a highwater mark in the annals of community relations. The Triumph streettracker, all glossy black and gleaming chrome, was making yet another photo pass, shredding the rural Oregon air with all the sound-baffling of your average 1960s Ascot Park half-miler, which is to say, squat.

A local horse rancher had heard enough. He approached our roadside group, head down, hands in pockets. “Well,” he said, looking up, pausing for effect. “I’m about to get my gun and shoot that bastard.”

Luckily, the builder of the blaring Trumpet, Kenny Dreer, had been a farrier in a previous career and once taken care of this man’s livestock. Apologies extended and manslaughter averted, the misbegotten delinquent in question was quickly flagged down and directed to short-shift his hindquarters to another location.

“Okay, so maybe it needs some baffles,” offers Barry Weiss, who commissioned the Triumph, though it’s doubtful if any obstructions will ever find their way into the custombent, ceramic-black open megaphones. Several of Weiss’ totally tweaked Britbikes have appeared in this magazine before (see “California Dreamin’,” CW, November, 1995 and “Rollin’ & Tumblin’,” CW, January, 1997). All are about as subtle as a cyclone, all are ear-splitters of the first order.

This Trackmaster Triumph, though, may be the most blatant. Hidden behind its ebony engine cases are several paychecks’ worth of thoroughly massaged internals, everything from lightened rockerarms to oversized intake/exhaust valves to resculpted piston crowns to a swiss-cheesed clutch basket. Dreer estimates the 750cc short-rod motor kicks out about 70 free-range horsepower. “Twist the throttle and the front end comes right on up in the first two gears,” he says with a wicked smile. “Out of an old British bike, that’s pretty exciting.” Less outrageous, less cacophonous, but equally appealing are Dreer’s bread-and-butter bikes, thoughtfully modified Norton Commandos and Triumph Twins, along with the occasional periodperfect restoration. His shop, Vintage Rebuilds (15120 S.

DAVID EDWARDS

More extravagance: Rather than the usual nickel-plating, Weiss' Trackmaster was treated to a chromed frame, which required an abundance of hand-sanding, two undercoats of copper, and yet more handwork before being immersed in the shiny stuff There was the small matter of a $1200 bill from the plating shop, but, "It came out like a diamond," beams Dreer.

Taking up residence atop the welded-on rear frame loop is another bit of trickery, a one-off fiberglass tailsection/stoplight. Working with bodyman Ted McGaillard—one of a band of local artisans called upon for paint, polishing, upholstery, engine work and specialty welding-Dreer came up with the humpback cowl’s nifty faired-in red lens. Attached unobtru-

sively to the seat base are a series of small ni-cad batteries plumbed into the Triumph’s charging system. Where’s the license plate? Trimmed, turned on end and mounted to a sheath covering the right shock, so it can be rotated in and hidden to preserve that flat-tracker flair. Don Weber did the seatcover out of buffalo hide; its bum-stop soon will be adorned with a sewn-on 8 ball, one of Weiss’ favorite icons.

Then there’s the bike’s absolute, over-the-top coup de grace, the Moon Eyes headlights/numberplate setup.

“Outrageous!” enthuses Dreer of the finished product.

“It’s loud and fast and the center of attention anywhere you take it.”

Rosenbaum, Oregon City, OR 97045; 503/631-8229), turns out between 16 and 20 complete machines a year.

“Triumphs and Nortons are beautiful pieces, we just make ’em tastefully different, enhancing the style of the bike,” explains Dreer.

A mechanic from childhood, when he helped his father run one of the East Coast’s largest foreign-car dealerships, Dreer was in the midst of a five-year sabbatical from the bike biz-shoeing the aforementioned equines-when opportunity knocked. An old British repair shop in Portland was closing its doors.

“A partner and I bought 20 years’ of inventory, including machine tools. There must have been 30 frames, 40 motors, cylinder heads stacked up like cookies, tons of it,” says Dreer. “It took truckload after truckload after truckload to move the stuff.”

Piecing bikes together out of this surplus merchandise was a natural, but Dreer wasn’t overly interested in bone-stock restorations.

“I love that classic 1950s Manx Norton look, it drives me crazy,” he says. “Why not build a modernized Manx using the smooth-running Commando Twin as a starting point?” Which is exactly what he did, beginning in 1993. It’s the Commando’s vibration-squelching Isolastic frame, introduced in 1968, that helps elevate a Vintage Rebuilds’

Norton out of cranky old classic status. “Nice thing about a Commando, you can ride it all day. Ride a Triumph at 65 mph for 50 miles straight, and you’ve had it,” Dreer says. “I’ll take the power, the smoothness of a Commando any day.”

Paradoxically, while Dreer’s rebuilt Nortons hark back to the Fifties, they’re about as modem as you can make a 30year-old design. Every crank is magnafluxed. Con-rods are balanced-“all grammed-out,” Dreer likes to say. Amal carbs, notoriously quick-wearing, are re-sleeved then fitted with new stainless-steel slides. Breaker points get the heaveho in favor of a Boyer-Brandsen electronic ignition. Precision Machine provides the valves, Hepolite the pistons, Audi the valve guides. Engine cases are buffed to a mirror sheen, and machined for lip-type oil seals. Dreer uses stainless-steel fasteners throughout.

Chassis-wise, he fits a triple-bolted, oversized swingarm spindle, improved Isolastic adjusters, new fork tubes, bushes and seals, Hagon shocks, Avon tires, Ferodo brake shoes/pads and hi-zoot Barnett cables.

“Everything is renewed; it’s more of a remanufacture than a restoration,” Dreer says. The completed bikes fairly glow with craftsmanship, almost as if a spotlight is trained on them from 50 rows up, following their every move. This part really matters to Dreer.

“Look, I don’t want to get caught up in a lot of psycho-babble here,” he starts. “But a craftsman who turns out highly skilled work shows not only mechanical aptitude, but a dedication, a love for the work. Mechanical skill is something that can be learned; it’s a necessary building block which must always be honed. But it’s dedication and passion that does the creating. There has to be a never-ending appetite for the next level of artistic expression.

“When I get finished with one of my Nortons, I’m excited. I still get a tingle from every bike I build. When I don’t, then I’ll know it’s time to close up shop and move on to something else.”

To date, Dreer has shipped about 15 of his Manxinspired specials.

“I’m sending these bikes all over the world, they have to be worthy,” he says. “The last thing I want is an angry phone call from Australia or Guam in the middle of the night.”

So far, Dreer’s sleep has been undisturbed. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontKickin' Ss

March 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWinter Storage

March 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

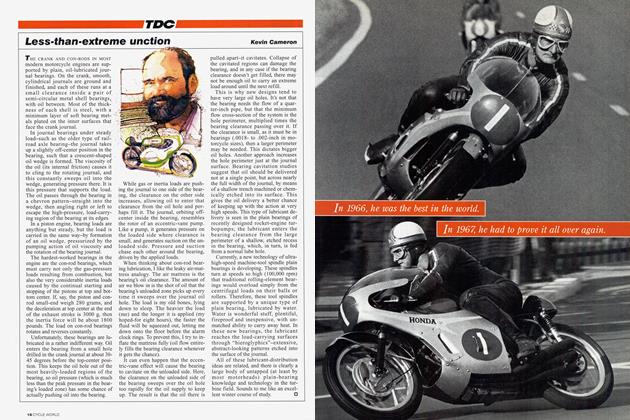

TDCLess-Than-Extreme Unction

March 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1998 -

Roundup

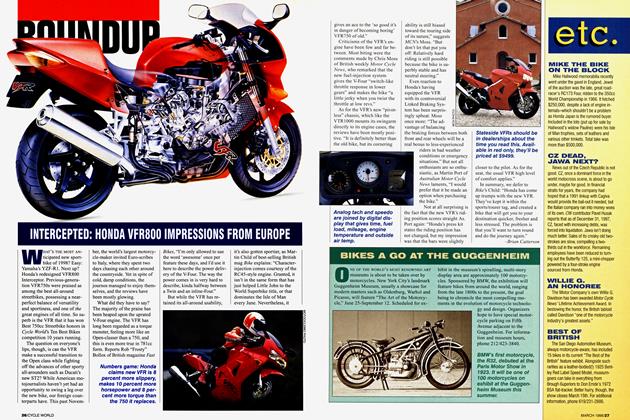

RoundupIntercepted: Honda Vfr800 Impressions From Europe

March 1998 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBikes A Go At the Guggenheim

March 1998