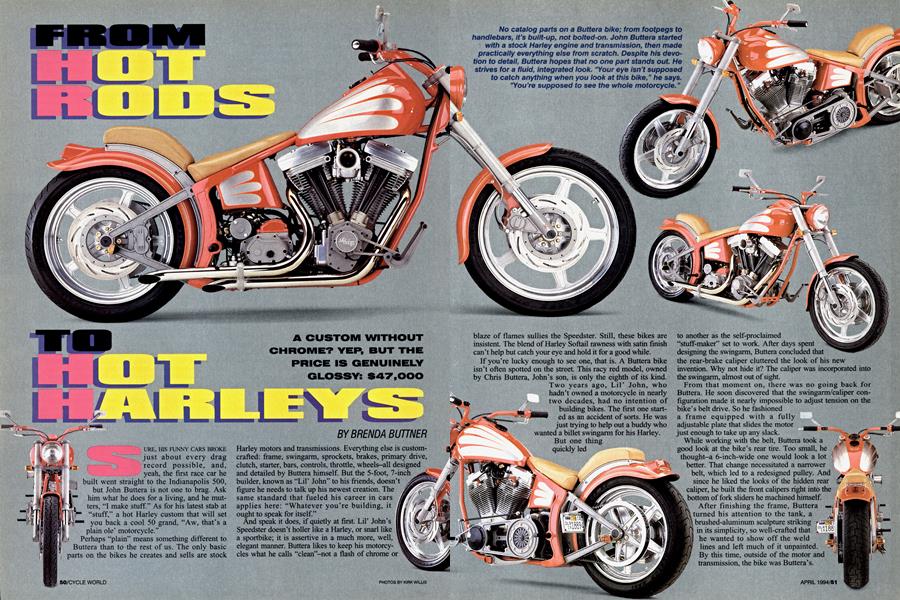

FROM HOT RODS TO HOT HARLEYS

A CUSTOM WITHOUT CHROME? YEP, BUT THE PRICE IS GENUINELY GLOSSY: $47,000

BRENDA BUTTNER

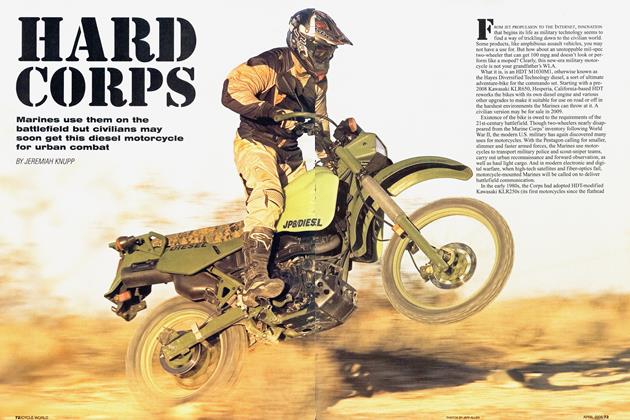

SURE, HIS FUNNY CARS BROKE just about every drag record possible, and, yeah, the first race car he built went straight to the Indianapolis 500, but John Buttera is not one to brag. Ask him what he does for a living, and he mutters, “I make stuff.” As for his latest stab at “stuff,” a hot Harley custom that will set you back a cool 50 grand, “Aw, that’s a plain ole’ motorcycle."

Perhaps “plain” means something different to Buttera than to the rest of us. The only basic parts on the bikes he creates and sells are stock

Harley motors and transmissions. Everything else is customcrafted: frame, swingarm, sprockets, brakes, primary drive, clutch, starter, bars, controls, throttle, wheels-all designed and detailed by Buttera himself. But the 5-foot, 7-inch builder, known as “Lil’ John” to his friends, doesn’t figure he needs to talk up his newest creation. The same standard that fueled his career in cars applies here: “Whatever you're building, it ought to speak for itself.”

And speak it does, if quietly at first. Lil’ John's Speedster doesn’t holler like a Harley, or snarl like a sportbike; it is assertive in a much more, well, elegant manner. Buttera likes to keep his motorcycles what he calls “clean”-not a flash of chrome or blaze of flames sullies the Speedster. Still, these bikes are insistent. The blend of Harley Softail rawness with satin finish can’t help but catch your eye and hold it for a good while.

If you’re lucky enough to see one, that is. A Buttera bike isn’t often spotted on the street. This racy red model, owned by Chris Buttera, John’s son, is only the eighth of its kind.

Two years ago, Lil’ John, who hadn’t owned a motorcycle in nearly two decades, had no intention of M building bikes. The first one start-

ed as an accident of sorts. He was just trying to help out a buddy who wanted a billet swingarm for his Harley, jj; But one thing quickly led

to another as the self-proclaimed “stuff-maker” set to work. After days spent v-designing the swingarm. Buttera concluded that the rear-brake caliper cluttered the look of his new invention. Why not hide it? The caliper was incorporated into the swingarm, almost out of sight.

From that moment on, there was no going back for Buttera. He soon discovered that the swingarm/caliper configuration made it nearly impossible to adjust tension on the bike’s belt drive. So he fashioned a frame equipped with a fully adjustable plate that slides the motor ^ just enough to take up any slack. While working with the belt, Buttera took a good look at the bike’s rear tire. Too small, he thought-a 6-inch-wide one would look a lot® better. That change necessitated a narrower belt, which led to a redesigned pulley. And * since he liked the looks of the hidden rear v caliper, he built the front calipers right into the |A\ bottom of fork sliders he machined himself.

After finishing the frame, Buttera —, JK\ turned his attention to the tank, a '«fU brushed-aluminum sculpture striking m in its simplicity, so well-crafted that . " ^ he wanted to show off the weld jflp lines and left much of it unpainted. HfJ/ By this time, outside of the motor and WÁ transmission, the bike was Buttcra’s.

And that meant LU’ John had finally met a modem motorcycle he liked. “I’ve been in and out of Harley shops probably 40 times in the last 15 years. I wanted to buy one,” says Buttera. “But I’d look at it and think, I can change this, I can do that. Pretty soon. I’m buying a brand-new motorcycle and throwing it away a piece at a time.”

One thing he didn't discard was the basic outline of the Harley Softail. But contemporary customs were a bit too “messy” for his tastes. The last bikes Buttera really liked were the Harley racers of 40 years ago. He believes that was “when motorcycles looked good. When they were a motor with two wheels that made ’em go down the road.”

The 54-year-old builder is no stranger to that look. Since the time he tore the fender off his first bicycle, he's been striving for a stripped-down look on whatever he creates. “Get rid of everything that doesn’t need to be there,” Buttera advises. That’s exactly what he did building hot-rods and drag cars in the ’60s and ’70s, and Indy racers in the ‘80s.

When Buttera decided to build a bike, he went to the people who helped him craft those cars. Mac Tilton, long a manufacturer of clutches on Indy cars, assisted in designing the clutch for Buttera's bike. Bob Stange of Strange Engineering, with years of experience building driveline components, lent a hand in creating the calipers. Steve Leach, skilled at making supercharger drives, aided in conceiving the primary and secondary drives. Steve Davis, who shaped all the bodies on Buttera’s hot-rods, sculpted the tank and fenders. Dennis Ricklefs, master pinstriper of cars, took his brush to the bike. “Take any one of them outta there,” says Buttera, “and that first bike would not have been built.”

But Lil’ John was always at the center of the project. It may be an understatement to say this became an obsession for Buttera. He often worked around-the-clock, around-thecalendar. “I decided to build as nice a motorcycle as I possibly could and not compromise anywhere.” His final test for the bike, as for all his projects: to look at it “and tell myself, ‘Yeah, that’s as good as I can do. There ain’t a part there that I cut a comer on.”'

As for how the bike cuts comers, let’s just say you won’t see it rocketing past the finish line at the Daytona 200. It is, for all its unusual parts and design, a cruiser, much more at home on a straightaway than a switchback. But even a short ride down the boulevard makes clear that this bike is very light for a custom. Steady and stable, too.

Which is more than can be said for Cycle World’s Feature Editor before her first ride aboard a Buttera. Dropping something this expensive is one thing. There was another: Before turning over the keys. Buttera, not one to mince words, said with a smile (but not a big one), “If you dent the tank, I’ll kill you.”

Don’t worry, the bike is fine. Quite fine, in fact. The main trouble taking it for a ride is getting past the admiring onlookers. It is, very simply, a bike that stops traffic.

Complaints? The suspension is a bit stiff, and the clutch a little abrupt, making tight U-tums a problem. The frontbrake lever feels mushy, in part because it’s operating only one disc. An integrated braking system links the rear caliper with one front caliper-via the foot pedal-while the right handlebar lever brings the other front disc into play.

Buttera hasn’t modified the Harley engine at all, and prefers that customers don’t tinker with theirs. “There’s no need to mess with that motor. It ain't a race motor, it’s a cruiser. If you want a fast V-Twin, go buy an Italian bike.”

It certainly would be cheaper to do so. Be prepared to shell out $47,000 for the privilege of owning a Buttera. No apologies from LiF John, though. "I didn’t start out with a price on my motorcycle. I just figured I wasn't gonna compromise. When I finished, I divided up the amount of hours and the price of material, and if anybody wanted one, they could have one.” There’s been plenty of interest. When word got around that Buttera was building a bike, five were sold before he finished the first one. All to satisfied customers, it seems. "Finest piece of machinery I’ve ever owned,” says Steve Leach, who has several thousand miles on his Buttera. Ron Craft, the proud rider of Buttera’s first bike, likes it better than his ’84 Softail and '93 Fat Boy. “It may not be big and bulky and angry enough for the hard-core Harley rider,” he contends. “But it’s by far the classiest of the bunch.'’

Of course, one man’s totally classy is another's too-conservative. But don't even bother asking Lil’ John to splash some painted flames on the tank or bolt a set of flashy pipes to the engine. Parked in a far comer of his shop stands the result of the only time he let a customer win an argument.

Garish purple with bright orange stripes and lots and lots and lots of chrome, the loaded-down custom screams where the other Butteras whisper. “It’s not my style,” Buttera grumbles, when asked about the bike. “If you ever see another one that looks like this in here again, I oughta be arrested for prostitution because I would just be doing it for the buck, and that’s not what I'm after.” To ensure that he doesn’t make the same mistake twice, Buttera plans to limit production to 20 bikes a year-all built in his one-man shop in Southern California (Lil' John’s Place, 17702 Metzler Lane, Huntington Beach, CA 92647; 714/848-4848).

Despite the very personalized signature Lil' John inscribes on each Speedster, he refuses to take much credit for the creation. “It’s a Harley-Davidson. That’s all it is,” he says matter-of-factly. But Buttera is still not satisfied with what it is. More changes are in the works. Future bikes will be fitted with carbon-fiber tanks and fenders. Buttera has been busy for weeks painstakingly designing and machining engine and transmission cases from the same anodized aluminum that graces much of the rest of his bikes.

Wait a minute. Engine cases? Transmission? Does Lil’ John plan to strip his customs of the few Harley parts they have? In typical soft-spoken style, Buttera won’t say much. But remember that this is the man who created custom VEights from a blank piece of paper. And the man who doesn't buy lamps for his house-he builds them “because I can do it.”

Come to think of it, a self-built V-Twin is exactly the kind of “stuff’ Lil’ John should have on his “plain ole’ motorcycles.” Œ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHigher Standards

April 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy A German Bike?

April 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCClass Struggles

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1994 -

Roundup

RoundupVr Harley Superbike For the Street?

April 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVr 1000 Parts For the People

April 1994 By Robert Hough