Great Expectations

RACH WATCH

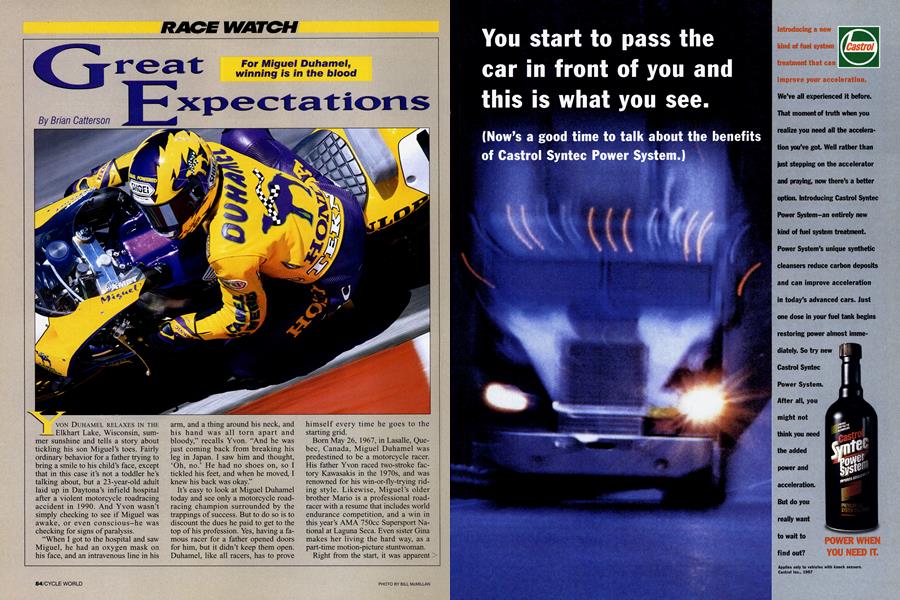

For Miguel Duhamel, winning is in the blood

Brian Catterson

YVON DUHAMEL RELAXES IN THE Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, summer sunshine and tells a story about tickling his son Miguel’s toes. Fairly

ordinary behavior for a father trying to bring a smile to his child’s face, except that in this case it’s not a toddler he’s talking about, but a 23-year-old adult laid up in Daytona’s infield hospital after a violent motorcycle roadracing accident in 1990. And Yvon wasn’t simply checking to see if Miguel was awake, or even conscious-he was checking for signs of paralysis.

“When I got to the hospital and saw Miguel, he had an oxygen mask on his face, and an intravenous line in his

arm, and a thing around his neck, and his hand was all torn apart and bloody,” recalls Yvon. “And he was just coming back from breaking his leg in Japan. I saw him and thought, ‘Oh, no.’ He had no shoes on, so I tickled his feet, and when he moved, I knew his back was okay.”

It’s easy to look at Miguel Duhamel today and see only a motorcycle roadracing champion surrounded by the trappings of success. But to do so is to discount the dues he paid to get to the top of his profession. Yes, having a famous racer for a father opened doors for him, but it didn’t keep them open. Duhamel, like all racers, has to prove

himself every time he goes to the starting grid.

Born May 26, 1967, in Lasalle, Quebec, Canada, Miguel Duhamel was predestined to be a motorcycle racer. His father Yvon raced two-stroke factory Kawasakis in the 1970s, and was renowned for his win-or-fly-trying riding style. Likewise, Miguel’s older brother Mario is a professional roadracer with a resume that includes world endurance competition, and a win in this year’s AMA 750cc Supersport National at Laguna Seca. Even sister Gina makes her living the hard way, as a part-time motion-picture stuntwoman.

Right from the start, it was apparent > that Miguel would follow in his father’s footsteps. From his humble beginnings on a two-stroke Kawasaki 100 dirtbike (with one shock removed because he was so light), he quickly advanced to the point where he was giving Mario a hard time on the 50 acres surrounding the family’s country chalet.

“Miguel hated to lose to Mario, even when he was on a smaller bike,” remembers Yvon.

Before long, Miguel joined his older brother in motocross racing. Advancing to the Schoolboy ranks, Miguel managed to win the Canadian 500cc Championship in his first ride on an Open-classer. “It was a one-race deal back then, and right before the race, my dad said, ‘You’re going to ride a 500.’ The first time I rode it, I popped the clutch coming out of a corner like you would on a 125 and the bike just exploded out from underneath me!”

In 1986, Miguel made his first foray into roadracing on a borrowed Yamaha RD350LC.

“It was my dad’s friend’s bike. He had a shop, and it was sitting in the back all full of cobwebs and everything. He said, ‘You can have it if you want it.’ We fixed it up real quick and rode it.”

The next season, Miguel added two more roadracing bikes to his stable, a Yamaha RZ350 and an FZ750. In due course, he started winning-much to the chagrin of his jealous competitors.

“We were so fast, we used to get torn down about every other weekend. Everybody would protest us, because we were beating Honda NS400s, which everyone knew were a lot faster than an RZ350. I didn’t pay too much attention, because I knew (the alleged cheating) wasn’t true. Anybody who had half a brain and saw those NS400s go flying by me so fast, and then saw me go 10 bikes deeper on the brakes, figured out pretty quickly that I was making up all the time right there.”

The 1988 season was remarkable not for the uncompetitive Kawasaki Superbike Miguel raced in Canada, but for his participation alongside his father and brother in the Bol d’Or 24hour endurance race in France.

“That was a pretty big stepping stone,” says Miguel. “During the night shift, when our Honda RC30 would run cooler, I was just as fast as the guys on the factory (Honda) RVF. But our pit stops were a complete joke; one time we had to wheel the bike down to the Honda France pits and have them use their air gun to take the rear wheel off! As a result, we finished seventh. But I was happy to see that my dad rode really well, because this was before the BMW Legends started, and he hadn’t been racing.” That Bol d’Or appearance served as a springboard for Miguel’s career, as he signed no fewer than three contracts for the 1989 season. He inked deals with Honda France to contest the World Endurance Championship, with Suzuki for the Canadian Superbike Championship, and with Lassak Racing to ride a Yamaha in the AMA 250cc GP class. But while Duhamel

impressed onlookers with strong showings in the Canadian round of the World Superbike Championship and in the Canadian/American Match Races, the year was most memorable for a leg-breaking crash during testing for the Suzuka 8-Hour.

“It was really lack of experience that caused it,” he says. “The Michelin guy I was working with back then didn’t care about me. I had about 80 laps on the front tire, and was sliding the front everywhere, saving it with my knee. But my lap times weren’t that good, and I thought I’d better come into the pits, which was the right decision.

“I mean, there I was, beginning my career in Japan surrounded by Honda and Michelin technicians. I said, ‘Man, the front’s plowing everywhere, it’s really bad.’ And he looked at the tire and said, ‘Oh no, it’s good for like 100 laps.’ So instead of me saying, ‘No, no, you’ve got to change it,’ I just jumped back on the bike. The second lap out, I lost the front and crashed in the fast kink under the bridge before the hairpin, and broke my femur. So I learned a lesson the hard way.”

Honda France dropped Duhamel for 1990, but he managed to land on his feet, signing a deal to ride a Yoshimura Suzuki in the AMA Superbike Championship. The season got off to a rough start, however, with the aforementioned get-off at Daytona that landed him in a hospital bed. Recovering from that, he was frustrated by overheating problems that caused the air/oil-cooled GSX-R750’s performance to deteriorate over the course of a race.

Matters improved midway through that season at Road Atlanta, where the Yoshimura team asked him to race its 750cc supersport bike. He promptly won, defeating dominant Muzzy

Kawasaki teammates Scott Russell and Doug Chandler. Then, at the penultimate series round in Topeka, Kansas, Duhamel hunted down and caught Chandler to claim his firstever AMA Superbike victory.

“I was really happy when I won at Topeka, because Doug was really tough, and I was on an inferior bike. My laps were fast-faster than qualifying, I think-and I never looked back,” he recalls.

Curiously, Yoshimura opted not to rehire Duhamel for 1991, leaving him without a ride. But then, a serious hand injury suffered by Commonwealth Honda rider Randy Renfrow during testing opened up a berth on the Martin Adams-owned team, and Duhamel got the job.

“It was real unfortunate, what happened to Randy-I’d rather have not gotten the ride than have Randy get hurt like that. But I remember talking to Martin, and telling him that I had a lot of faith in my ability. I told him just to give me a chance,” he says.

Duhamel’s argument may have been convincing, but his victory in the 50th Daytona 200 was more so.

“I remember the race, just completely dominating...just riding around, feeling good, and pulling out a second per lap. I was just amazed,” says Duhamel.

So, too, was dad Yvon: “I had to pinch myself, like I was dreaming. I thought it would take a couple more years before he won Daytona. I tried for 14 years and never won!” Unfortunately, a mechanical failure and a crash while leading at Topeka put pay to Duhamel’s Superbike Championship aspirations for that year. But he did earn his first 600cc Supersport title, winning seven of nine races on the new CBR600F2.

Shortly thereafter, Duhamel got the call every young racer dreams of: Christian Sarron was looking for a French-speaking rider for his Yamaha 500cc GP team (sponsored by Banco, the French lottery), and wondered if Miguel would be interested. Duhamel jumped at the chance-and soon found himself in the deep end of the pool.

“The bike was so bad,” he recalls. “I remember Wayne Gardner telling me, ‘You’ve got to ride that thing harder.’ And I told him, T can’t. I can’t even turn it. I go into corners, and I ride off the edge of the track.’ ”

Riding the evil-handling YZR500 gave Duhamel a taste of what Wayne Rainey had to overcome to win that year’s 500cc World Championship. And like his current AMA Superbike rival Doug Chandler, Duhamel found himself awestruck.

“Wayne just rode so hard. I remember thinking in ’92 that if Wayne could win on this bike, he’s a hero,” Duhamel says. “Not a whole lot of people, I think, can appreciate that championship the way I can, because I was there, on that Yamaha, which was the worst bike ever made by man!” To cap off his fraught GP season, Duhamel was unceremoniously sacked. That didn’t sit well with him then, and it still angers him today.

“Looking back now, it makes me mad, because my team told me to take it easy that first year and it would be okay. I was afraid of crashing and having everyone think I was riding over my head, which I wasn’t. I guess I should have gone for it,” he says.

The following year saw Duhamel return to Kawasaki, this time with Rob Muzzy’s U.S.-based team. It was a seesaw season, with a frustrating breakdown while leading at Mid-Ohio followed by a face-saving victory in the Sears Point finale. The quest for the 600cc Super-sport Championship went better, however, as Duhamel won seven of 10 races en route to his second title.

Following another round of aggressive marketing by his manager, former racer Alan Labrosse, Duhamel found himself in a most unlikely place for the 1994 season-debuting the factory Harley-Davidson VR1000 Superbike. The program got off to a slow start with an embarrassing engine failure at Daytona in full view of the pits, but soon gathered momentum. By MidOhio, the team had achieved some semblance of reliability to match the VR’s stellar handling, and Duhamel managed to qualify on the front row > and lead the race-until he pitted with a loose shift lever, that is. And then, in the following round at ultra-fast Brainerd, Minnesota, he again qualified well, and led the race on the way to an eventual fourth-place finish.

The following year, 1995, saw Duhamel reunited with the Camel Honda team, which by now had changed its name to Smokin’ Joe’s. For team owner Martin Adams, it was a joyful reunion.

“When Miguel told me he was going GP racing in 1992, I wanted to die. I think the people in Europe spin great, smoked promises for young riders, and more often than not, that’s what it is-smoke. We were here to deliver for Miguel, and I think had he stayed, we would have had an absolutely marvelous season together in 1992.

“We came in second in several bidding wars for his services,” Adams adds. “That’s when I was operating the team with a fixed budget from American Honda. It got much better with Camel’s involvement.” Though neither Adams nor Duhamel will say, Duhamel’s salary is reputed to be closer to seven figures than to five.

Again, Adams’ faith in Duhamel was validated, as the Canadian swept to a record six straight victories en route to his first Superbike Championship. And he fared even better in the supersport ranks, where he posted a record eight straight wins on his way to his third 600cc title. For his efforts, Duhamel received the AMA’s coveted Pro Athlete of the Year award.

For the first time in his career, Duhamel stayed put for 1996, and turned in another outstanding performance on the Smokin’ Joe’s Hondas. Again, he rode a CBR600F3 to the 600cc Supersport Championship (his fourth), and he very nearly retained the number-one plate on his RC45 Superbike. Despite a violent crash while leading at Laguna Seca, and a loose shift lever at Sears Point, Duhamel stayed in the running until the series finale at Las Vegas, where tire troubles handed Kawasaki’s Doug Chandler the win-and the title.

But critics are quick to point to Duhamel’s four wins versus Chandler’s one, and cite the AMA’s points structure as the real reason Duhamel was unseated.

Duhamel explains the situation: “There was a big discrepancy between Laguna, where I crashed, and Brainerd, where Doug broke. I mean, he was on a plane going home by the end of the race, yet he got points, whereas > I crashed while leading on the last lap and got zero points. I don’t think it should be a lottery where depending on how many riders are in the race, you get points or no points.”

This year hasn’t proven any easier for Duhamel. The RC45 has been plagued by tire woes, and there’s renewed competition in the 600cc Supersport class in the form of the new Suzuki GSX-R600. At the halfway point of the 10-race series, he’s winless in Superbike, and has only won three Supersport races. With Ferracci Ducati rider Mat Mladin winning three races and Muzzy Kawasaki’s Chandler leading the points chase, the ’97 Superbike Championship is probably out of Duhamel’s reach, but he remains optimistic about his odds of retaining his Supersport crown. And at age 30, he feels he’s got a lot of good years left in him.

“I’d like to go back to the GPs,” Duhamel declares. “I’d be more ready, mentally, as far as living there. But I think the most important thing is to be more assertive with my setups. Because in the GPs, if you’re a little unsure, the teams tend to take over.

“In ’92, I was so intimidated. I mean, you’re talking to people who are telling you, ‘This is not a motorcycle, this is a 500cc grand prix bike.

You can’t ride it like a normal motorcycle. You’ve got to pray before you ride, and then when you ride, you’ve got to close one eye and downshift with your right toe.’ It’s like, what are you talking about? It’s a motorcycle.” Somehow, you get the feeling Miguel Duhamel will manage just fine. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1997 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1997 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

September 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1997 -

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Bimota's Two-Stroke Hits the Street

September 1997 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! New Yamaha Superbike

September 1997