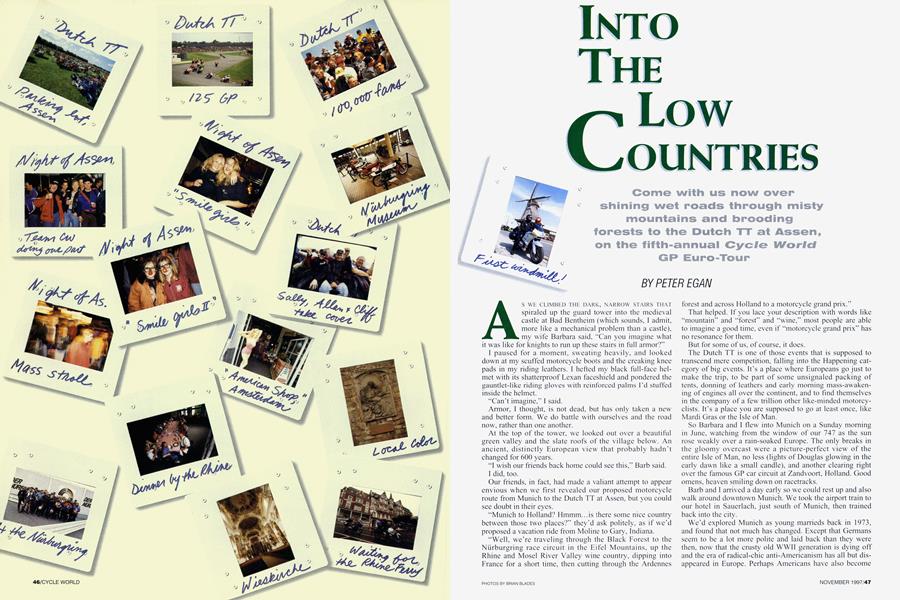

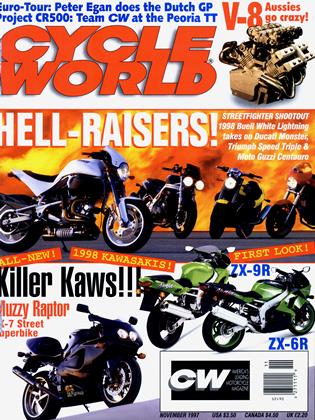

INTO THE LOW COUNTRIES

Come with us now over shining wet roads through misty mountains and brooding forests to the Dutch TT at Assen, on the tifth-annuaI Cycle World GP Euro-Tour

PETER EGAN

A s WE CLIMBED THE DARK, NARROW STAIRS THAT spiraled up the guard tower into the medieval castle at Bad Bentheim (which sounds, I admit, more like a mechanical problem than a castle), my wife Barbara said, `Can you imagine what it was like for knights to run up these stairs in full armor?" I paused for a moment, sweating heavily, and looked down at my scuffed motorcycle boots and the creaking knee pads in my riding leathers. I hefted my black full-face hel met with its shatterproof Lexan faceshield and pondered the gauntlet-like riding gloves with reinforced palms I'd stuffed inside the helmet.

"Can't imagine," I said. Armor, I thought, is not dead, but has only taken a new and better form. We do battle with ourselves and the road now, rather than one another.

At the top of the tower, we looked out over a beautiful green valley and the slate roofs of the village below. An ancient, distinctly European view that probably hadn't changed for 600 years. "I wish our friends back home could see this," Barb said. I did, too.

Our friends, in fact, had made a valiant attempt to appear envious when we first revealed our proposed motorcycle route from Munich to the Dutch TT at Assen, but you could see doubt in their eyes. "Munich to Holland? Hmmm. . . is there some nice country between those two places?" they'd ask politely, as if we'd proposed a vacation ride from Moline to Gary, Indiana.

"Well, we're traveling through the Black Forest to the Nürburgring race circuit in the Eifel Mountains, up the Rhine and Mosel River Valley wine country, dipping into France for a short time, then cutting through the Ardennes forest and across Holland to a motorcycle grand prix."

That helped. If you lace your description with words like "mountain" and "forest" and "wine," most people are able to imagine a good time, even if "motorcycle grand prix" has no resonance for them. But for some of us, of course, it does.

The Dutch TT is one of those events that is supposed to transcend mere competition, falling into the Happening cat egory of big events. It's a place where Europeans go just to make the trip, to be part of some unsignaled packing of tents, donning of leathers and early morning mass-awaken ing of engines all over the continent, and to find themselves in the company of a few trillion other like-minded motorcy clists. It's a place you are supposed to go at least once, like Mardi Gras or the Isle of Man. -

So Barbara and I flew into Munich on a Sunday morning in June, watching from the window of our 747 as the sun rose weakly over a rain-soaked Europe. The only breaks in the gloomy overcast were a picture-perfect view of the entire Isle of Man, no less (lights of Douglas glowing in the early dawn like a small candle), and another clearing right over the famous GP car circuit at Zandvoort, Holland. Good omens, heaven smiling down on racetracks.

Barb and I arrived a day early so we could rest up and also walk around downtown Munich. We took the airport train to our hotel in Sauerlach, just south of Munich, then trained back into the city.

We'd explored Munich as young marrieds back in 1973, and found that not much has changed. Except that Germans seem to be a lot more polite and laid back than they were then, now that the crusty old WWII generation is dying off and the era of radical-chic anti-Americanism has all but dis appeared in Europe. Perhaps Americans have also become

BRIAN BLADES

better guests. At any rate, people were polite and helpful every where we went. -

Ah, Munich. Wonderful beer at the Hofbrauhaus, and a central market square of aromatic foodsroasting sausages, blue cheeses, smoked fish, pickled eels, baking .~111JP.~¼.'U I I~II~ }JI~I%I~.~..I Ua1~iII~ breads and pastries-all arranged around a shaded park and bustling beer garden. "I think we should rent an apartment here and move to Germany," I told Barb. "Just eat and drink for a hobby and see if we can get our weight up to around 300 pounds."

"How do Europeans stay so thin?" Barb wondered aloud. "Bicycles," I suggested. They were everywhere. Back at the Sauerlacher Post Hotel, our small band of brothers and sisters gradually assembled for this, the fifthannual CW GP Euro-Tour, arriving by Edelweiss courtesy bus. The bus was piloted by our revered guide of former trips, Joseph "Fuzzy" (pronounced "Futzi") Hack! and a new guide named Christian Preining. Both are Austrians who speak excellent English, though Fuzzy is famous for adding colorful new idioms to the English tongue. At the morning briefing, he informed us that our easy first day's ride would be "A sheet of cake." One of our group accused him of speaking "Germonics."

We had lots of first-timers on the tour, but also a good number of Euro-Tour vets, including a reunion group of high-spirited riding buddies from the 1995 Czech UP tour who call themselves the Spitzbüben, which is German for "mischievous boys." They seemed to have a lingering reputation among the Edeiweiss guides as the Katzenjammer Kids of Europe, wanted by Interpol in several countries for unpaid speeding tickets, accidental wheelies, passing tour buses at the speed of light and other crimes of gusto.

Others were from all parts of the country, but besides Barb and me, there were only two other couples: Allan Engel, a ship's captain from California and his landscape architect friend Sally Dunn; and Tom Overby, a tax lawyer from Little Rock, who brought his college-age daughter Audrey along for her first trip to Europe.

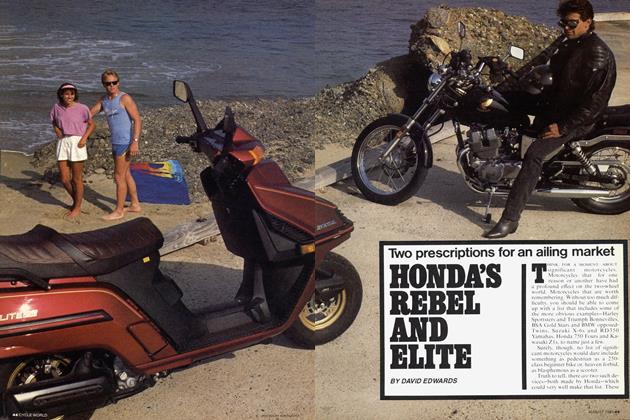

Also on the trip were CW Editor David Edwards and staff photogra pher Brian Blades, an old friend and former dirt rider who'd been brushing up on his Street technique for this trip. Filling out the list was Werner Wachter, owner and founder of Edel weiss Bike Travel a pleasant fellow of quick intelligence who looks as if he could be an Austrian ski instructor. And maybe is, for all I know.

Rain hammered against our window like lead pellets in the morning and hotel hallways were alive with riders rustling around in rain gear, sounding like 25 fat ladies in nylons and barn boots. After breakfast and a morning brief ing, we walked to the bikes. Our motorcycles were a mixture of new-generation BMWs of all types, and Suzukis, mostly 1200 Bandits. I had requested a BMW Ri 100RS-I've been thinking for several years about buying one (but have, so far, been too cheap), and I wanted to renew the acquaintance.

Our group left Sauerlach in clumps and batches, with a few lone riders, some following the guides, some not. The beauty of Edelweiss tours is that (a) everyone has a map and (b) your only responsibility is to arrive at the next hotel for dinner. Barb and I followed Werner (I hate turning the wrong way out of the hotel parking lot), along with David, Brian and a few others.

Werner led us through a light misting rain through the green, lovely Bavarian hill country and farmland west of Munich on two-lane roads. Brown Swiss dairy cattle watched over split-rail fences as we passed; citizens of half timbered villages paused in their chatting and stepped up on the curbs; men in lederhosen, Tyrolean hats and loden-green jackets (but without accordions) regarded our silver-green BMW with approval. The Alps loomed, shrouded in swirling clouds, just to the south.

Germany has lovely roads for riding motorcycles. Smoothly paved, they curve and dip and follow the contours of the land. Villages are often no more than 7 or 8 kilome ters apart, but the roads between are sparsely traveled and almost entirely unpatrolled by Polizei.

Germans-and Europeans in general-seem not to have developed this simmering, Puritanical disapproval of speed you find in America. Once they are out of the city, Germans simply travel at whatever logical speed is suggested by the road and the capability of their vehicles, be it 65 or 90 mph. Even in slow vehicles, they don't begrudge other people who can go faster. This makes for nice riding; almost heav enly, by our standards.

On the autobahns, of course, there are no speed limits. There, I discovered our Ri 100RS would hit 215 kph (about 135 mph) if we sat in normal riding positions and did not go into a tuck, but the wind flow and noise were a lot more pleasant below 180 kph, and we settled on 160 (about 100 mph) as the most serene cruising speed.

Which, where we live-the Land of the Free-would get us thrown in jail and our bike towed.

Following Herr Wach ter across Bavaria to our J evening destination of Bad I Urach removed some of / the map-reading strain, but even Werner was confused at times Germany is a hard country in which to navigate. Unlike, say, France, which has numbered roads, Germany depends on clusters of desti nation signs to point the way. You come to a sudden crossroads, and instead of an arrow that says "Route 19" you are confronted with one small yellow sign that says...

Marktoberdorf Klosterlechtfeld Totenschwei n hocks m itstuffi n

.and another one that reads...

Pfizerknottend I nkelrude Rotenkaisersunterwarren Bad Rainagain Behang inwashonderseigf riedli ne

As you go flying past the intersection at about 120 kph, your navigator/wife leans forward and shouts, "What did those signs say?"

Struck completely dumb in the presence of a thousand Teutonic syllables, you simply skid to a stop and put your head down on the tank and groan.

N evertheless, we found our way. Stopped for lunch next to a spectacular 18th-century Rococo church called Wieskirche. There we took over a small cafe and dined on the famous Bavarian Weisswurst, a white veal sausage required by stern tradition to be eaten before noon, while theoretically still fresh-"even if it's been frozen and thawed," Werner explained with a wry smile.

Evening found us at an excellent hotel in Bad Urach. Bad, of course, means mineral bath or spa, so David and our mutual old touring buddy Charles Davis set out to find a mineral bath and a rubdown, which they did, arriving for dinner looking 10 or 20 years younger. We all had our evening Weissebier (everything in Bavaria is whitesausage, beer, mountains, flowers, etc.) and then filed into a grand old dining room for dinner. Someone asked a waitress what was for dinner and she replied, "Meat!"

"Meat," in southern Germany, means small, tooth-resis tant curls of roasted pork in a bland white gravy, with some form of potato on the side, and this substance is the main reason that Italian restaurants are more numerous in America than German restaurants: a classic case of Fleischfurcht, or "meat fear."

At dinner that evening, we learned that one of our group, Todd Borchart, an irrepressible character and Italian GP Euro-Tour veteran who goes by the nickname "El Chico Loco," had slid wide on a wet corner and hit the side of a truck. His bike was bent and his right leg was broken, but he was doing well at a nearby hospital.

I should say his leg was re-broken, as he'd injured the same leg in a desert dirtbike crash years ago and it had never healed properly. Word was, the German surgeons were trying to straighten out both the old and new damage. A very long day's Wednesday ride took us across the Neckar River, on magnificently curvy roads through the heart of the Schwartwald, or Black Forest, across the Rhine, into French Alsace and the vineyards of the Vosges Mountains, back into Germany and into the famous Mosel wine region for a night at Bernkastel-Kues, a name that has appeared on many empty wine bottles in my lifetime.

Barb and I rode mostly alone that second day, stopping for coffee at a café in Johanniskreuz, Germany's answer to the Rock Store, a gathering place for riders. There were a few motorcyclists at the café, but not many. Then two huge tour buses full of gray-haired German ladies arrived and swamped the place. They surrounded our table and jostled our chairs, crackling and chatting in shrill German tones. It was like a scene from Hitchcock's The Birds.

We left in search of oxygen. On the road, fellow tour member Peter Wylie on his Suzuki TL1000 passed us with a wave, sailing off into the distance at high speed. Five miles later, we found him standing in the road next to his bike, at the end of a 50-yard streak of rubber. As he was accelerating through the gears, his trans mission had suddenly seized up solid in fourth gear, lock ing the rear tire. The TL had been a testbike for several German magazines, so its trans had probably seen better days.

iiau piuuauiy ccii UL~LLL4 uay~. We dragged the bike into a handy rest area and left it for the chase truck to retrieve, then Peter hitched a ride on the back of David's R1100RT. Fuzzy and Christian conjured up a new bike and Peter was back in action the next day.

Our own machine, the R1100RS, was proving itself a good choice for the trip, with just one minor glitch. It had an onloff throttle sensitivity that caused it to surge at low speed, but I soon learned to compensate by being a littie more subtle with the right wrist. My only other complaint was with the saddlebags, whose multi-step, easily bent lock ing mechanisms were a constant source of cursing, mis placed keys and minor frustration. (I picture their inventor now living in a madhouse, catching flies in a jar and mutter ing incantations to himself.) BMW had the greatest bags in the world on my old 1984 RS, then changed them. Go figure. For all that, I'd still like to have a new RS, just for all of the things it does so well. It goes, handles, stops and car ries two people in swift, compliant comfort. Looks good, too, I think.

On yet more mind-bogglingly lovely roads we dropped down into the Mosel River Valley, passed the great and impossibly charming riverside towns of Bernkastel and Kues, then climbed through some of the world's most renowned vineyards to a modem hotel that looked like CIA headquarters, but with pink porch panels. That night we had "meat" for dinner again, but first celebrated the long day's ride with a glass of the local Weisswein (more white stuff) and an excellent Bemkastler Riesling.

People have been making-and drinking-fine wines here for at least 2000 years, ever since nearby Trier was a Roman outpost (hundreds of Roman wine goblets have been recov ered in excavations around Bernkastel), and the proconsul Ausonius sang its praises in poem, thanking Bacchus for sending him here. We did, too.

As I sipped this ancient magical potion and looked across the river at the ruins of a castle on the opposite bank, I had one of those European Moments. This is a short reverie in which you suddenly glimpse the deep, saturated oldness of Europe and are temporarily humbled at the ridiculous short ness of your own generation's moment in time.

Telelever front end? Electronic fuel injection? A blink of the eye. It's the vines that last. And those goblets. Good basic technology for the ages.

A third day of hard travelin' took us all the way to Holland, but not before we'd visited the car and motorcycle museum at the Nürburg ring, followed the borders of Belgium and had lunch in the beautiful old vil lage of Monschau.

We sat at an outdoor café in Monschau (in a blessed calm between rainstorms) and I looked at the map. We were not far from Malmedy, Rocherath, St. Vith-Battle of the Bulge country in WWII. My father-in-law, then a young Captain Fred Rumsey, had fought his way through these very hills in 1945, los ing most of his buddies on the way. His unit was given a presidential citation for destroying 78 German tanks during three days of bitter street fighting in Rocherath, just 15 miles from our lunch stop. Fred was awarded a bronze star for his part in the struggle. Nasty times for such beautiful country. We hit the road again, into the teeth of yet another rain storm

A word about rain here: It rained every day on our tripDavid Edwards would later refer to it as "The Wet Crotch GP Tour"-with only a few inter ludes of fleeting sun and dry road. Yet somehow it didn't matter much. Once you've gone through the cursed pro cess of donning your rain suit, wet-weather riding has its own restful rhythm and beauty, and the green European coun tryside can look quite dramatic with shafts of sunlight breaking through midnight-blue storm clouds. There's a Wagnerian wildness about it that suits the Rhineland. How's that for cheerful?

At Emmerich, we finally breezed into Holland, crossing the Rhine into a sunlit Dutch afternoon with looming graywhite clouds from a van Ruisdale painting. After the rugged hills of Germany, Holland is almost soothingly soft; a flat, carefully stitched tablecloth of tidy villages with intricate red brickwork, sleepy canal-boat traffic, straight roads lined with shady poplars and fields of flow ers with bicycle paths cutting through them, all seen through a dreamy, moisture-laden atmosphere. In Germany, the land is the scenery; in Holland, it's that sky that dominates.

We followed two-lane roads past Amhem, then picked up the A28 four-lane past the town of Assen to our hotel in Groningen, just to the north. We had a free day before the races, so Barb and I joined David, Brian and Charles for an all-day train excursion into Amsterdam. The coach-class cars were almost full, so we feigned stupidity and rode in an empty first-class compartment-until the conductor checked our tickets.

"These are very lovely tickets," he said, "but, unfortunate ly, they are not for this first-class car." (Almost everyone in

Holland speaks perfect English, which is more than you can say for the U.S.) "Gosh-all-fish-hooks!" we said, or words to that effect, and moved.

Amsterdam, with its webbed canals and tall, vertical hous es, is one of the great cities of the world, but it seems over whelmed these days by its own reputation for tolerating almost everything. The upshot is a rather sleazy mix of ama teur art, sex shops, head shops, panhandlers, backpackers, hustlers and ladies of the night (or morning or afternoon) sit ting in neon display windows. It was a good place to be for about three days when I was 21, but the city feels to me now like the landscape of Austin Powers, International Man of Mystery, something left over from another time: A little tired.

The museums, the scenery and the Indonesian food were great, though. We had a fine lunch and took a canal-boat ride while Brian went to the Rijksmuseum, which Barb and I had seen on our first visit in 1973. At lunch, Barb said, "One thing I like about this place, is you don't hear all those annoying European police sirens, like you do in Munich." "That's because nothing is illegal here," David explained. "Who would you arrest?' Good question.

Saturday was race day, but the Friday night before was festival night in downtown Assen. Unlike Douglas at the Isle of Man, which is Bike Central, Assen has its guests park just outside the barricaded downtown, which is as charming as Disneyland's European Village, but real. Bands play on every other street corner, bungee jumpers leap from cranes, beer tents sell beer, food tents sell pretzels and sausages, and everybody walks.

Everybody: kids, grandmas, bikers, riders in full leathers, moms, young couples with prams, all circulating in a huge, swirling counter-clockwise flow through jam-packed streets. No pushing, shoving or swaggering, just a polite, cheerful crowd out for a mass stroll. I've never seen anything quite like it. In the U.S., we seldom get an all-ages family crowd at a bike rally.

On Saturday we rode to the track, joining the flow down A28 until we were ducted into one of a dozen parking fields whose size and glittering mass of handlebars, gas tanks and headlights almost defies description. How many bikes do you picture on Earth? Triple that number, square it and then multiply by your age and envision them all parked at Assen. Ever wonder where all the cowhide goes when McDonald's is done making hamburgers?

Leathers. At Assen. We hiked around the track to our excellent grandstand seats at a fast left-hander on the back side of the circuit, with a good view of several other corners and part of the main straight. Assen is a bikes-only venue (no car races) so the seating is pleasantly close to the track, which is flat but fast and interesting.

I won't go into details on the race, except to say that the 250 GP, won by Tetsuya Harada on an Aprilia, was a barn burner, and a better race than the 500. Mick Doohan is so good on the big bikes that no one can really stay with him. Makes you long for a Schwantz, Rainey or Lawson to keep him honest.

With the GP over, it was fast autobahn riding back toward Munich, but not before we'd hit the two-lane Romantische Strasse (quite literally "Romantic Road"), stayed in the lovely Rhine-side town of Andernach and visited a couple of fine castles at Berg Eltz and Bad Bentheim. An outdooor lunch was prepared for us by Fuzzy-who is an actual chef in his other life, and always makes the best meals of the trip-at

a park on the famous Lorelie Rock over looking the Rhine.

This is where the Rhine Maidens used to sing their siren songs and lure sailors to their deaths against the rocks. I went to high school with girls like this, and I can tell you the risks are not overstated.

We later stopped again at the Nürburgring, the famous 14-mile race circuit nestled in the Eifel Mountains. The track was open for anyone with the 22 deutchmark ($13) per lap fee. So our group lined up behind various Porsches, taxicabs full of tourists, sportbikes and teens in hot-rodded Opels (can you imagine this happening in America?) and paid our money, just as the rain began pouring down again. Before we pulled onto the track, Christian walked up and said, "A roadracing friend of mine recently won a race here in the rain because he didn't crash. He normally fin ishes 14th." He peered in through my helmet visor to see if I understood.

Message delivered. The track was indeed quite slippery in the rain-slick with oil and rubber-so we didn't exactly set any new two-up lap records, but the length and difficulty of the track, one of the most beautiful on Earth, made its impression. With 174 corners per lap, you feel like you've been gone for a month when you finally get back to the start-finish line. And, in my case, I probably had.

Another key stop on the way home, our last night on the road, was the fabled city of Rothenburg. The last 100 km into town, Barb and I joined up with the dreaded Spitzbüben and shared a very fast, exhilarating ride on narrow valley roads along the Tauber River. It was fun, but I couldn't help thinking that if I rode the whole trip at this pace, fate would eventually catch up with us and smite us on the kneecap or elbow. Nevertheless, I arrived in Rothenberg on an adrenaline high, with virtually no cob webs on my sidewalls or brake rotors.

Rothenburg is perhaps Germany's best preserved medieval walled city. Once reduced to a half-populated eco nomic backwater by the predations of the Thirty Years War and the Black Plague, it was finally rediscovered in the last century. Heavily shelled during WWII, 40 percent of it had to be re-rebuilt to original plans.

When you look at these beautiful old half-timbered homes and inns, exquisite cathedrals and civic buildings, and think of them being bombed and shelled, it occurs to you that the German people should have beaten Hitler to death with his own hat, just for the architectural damage he brought down on the country, let alone the human suffering inflicted on the world. Centuries of hard work, artisanship and inspiration, gone in a flash of bad temper, like a child breaking his own toys.

We took an evening tour of Rothenburg with the caped and hooded night watchman, a man whose role is as old as the medieval city. He carried a lantern and a pike and gave us a fas cinating lecture as we walked through the narrow cobblestone streets and looked out over the parapets withaftill moon rising.

Another European Moment: My grandfather came from Germany in 1910, and I could suddenly imagine his ances tors living this life, seeing this view from a castle wall cen turies ago, the night and the watchtowers freighted with different meanings than they had now. I felt like the tempo rary genetic expression of something much older than myself. That, or a character in a Donovan song.

Last day. The road from Rothenburg was one of the best of the trip. We dipped, swooped and plunged through the hills of the River Aitmuhi region and then descended through the Aitmuhital Naturpark in warm sunlight and headed south to the ring road around Munich for one last good drenching rainstorm before we pulled up at the Sauerlacher Post Hotel End ofjourney El Chico Loco rejoined us for din ner that night seated in a wheel chair Seems the surgeons had not only fixed his bro ken leg, but re paired the botched job done by an

American hospital back in the Seventies 6 S1z~P after his dirtbike accident. He read us a hilarious account he'd ,4,lt4L~L4t4t~.4 written of his week in the hos. .. .. pita!, and said he'd seen the Dutch TT on TV in the hospital lounge, sipping champagne ordered from the maternity gift shop.

Seems a German policeman came to his hospital room and served him a traffic ticket for going too fast. "I was going fast," Chico told him, "but certainly not too fast. If I'd been going too fast, I'd be dead. All I've got is a broken leg." The cop agreed and reduced the fine. A happy ending, all things considered.

As everyone made farewell speeches, I looked around the room and thought no two European motorcycle trips are quite alike. I've been on three Edelweiss tours now, and on every one you meet new people, cover new ground, and try to comprehend a thousand things you've never seen. A fast-moving motorcycle trip here is essentially a compres sion of life. It's an unrelenting succession of impressions that unwind just ahead of your front wheel and leave a sin gle vision of the trip that is as complex and full of details as a Gothic cathedral, yet all one thing, complete in itself

Later, you frame that picture in your mind and it stays with you as almost nothing else does. And when people ask later, "How was that ride from Munich to Holland?" you don't even know where to begin. "Like going from Moline to Gary," you joke, "by way of the Middle Ages, with mountains and forests and wine and racetracks."

Next year, sunny (yes, please!) Spain for Cycle World `s sixth-annual GP Euro-Tour. Join us! Atpresstime, the 1998 GP schedule had not been set, but the Spanish Grand Prix always takes place in early May. For more information or to make reservations, phone Edelweiss Bike Travel at 800/8 772784 on the East Coast or 800/582-2263 out West.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue