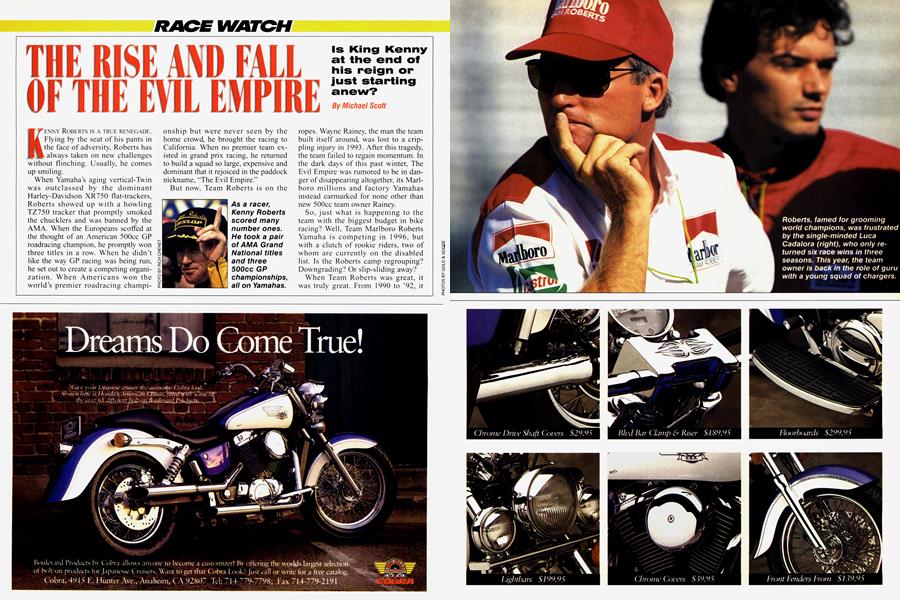

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE EVIL EMPIRE

Is King Kenny at the end of his reign or just starting anew?

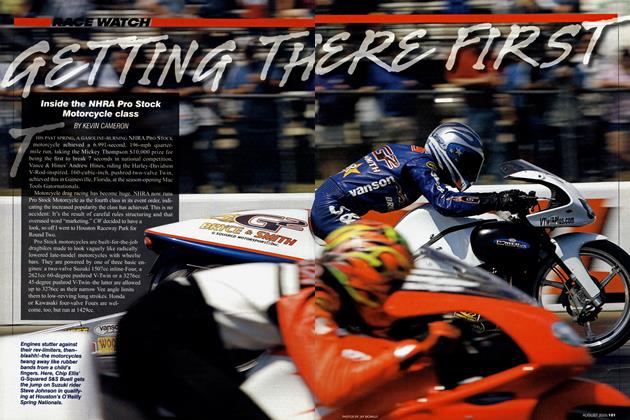

RACE WATCH

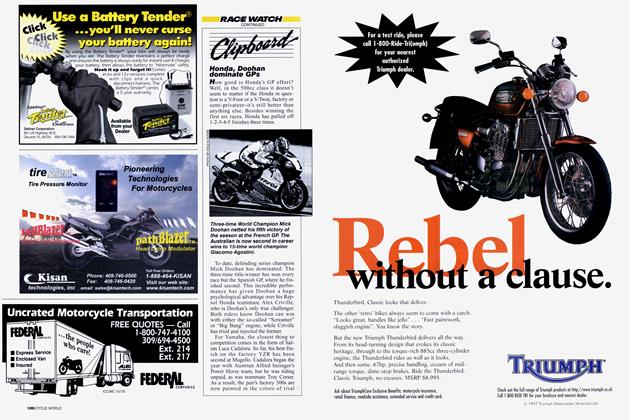

Michael Scott

KENNY ROBERTS IS A TRUE RENEGADE. Flying by the seat of his pants in the face of adversity, Roberts has always taken on new challenges without flinching. Usually, he comes up smiling.

When Yamaha’s aging vertical-Twin was outclassed by the dominant Harley-Davidson XR750 flat-trackers, Roberts showed up with a howling TZ750 tracker that promptly smoked the chucklers and was banned by the AMA. When the Europeans scoffed at the thought of an American 500cc GP roadracing champion, he promptly won three titles in a row. When he didn’t like the way GP racing was being run, he set out to create a competing organization. When Americans won the world’s premier roadracing championship but w;ere never seen by the home crowd, he brought the racing to California. When no premier team existed in grand prix racing, he returned to build a squad so large, expensive and dominant that it rejoiced in the paddock nickname, “The Evil Empire.”

But now. Team Roberts is on the

ropes. Wayne Rainey, the man the team built itself around, was lost to a crippling injury in 1993. After this tragedy, the team failed to regain momentum. In the dark days of this past winter, The Evil Empire was rumored to be in danger of disappearing altogether, its Marlboro millions and factory Yamahas instead earmarked for none other than new 500cc team ow ner Rainey.

So, just wTat is happening to the team with the biggest budget in bike racing? Well, Team Marlboro Roberts Yamaha is competing in 1996, but w ith a clutch of rookie riders, two of w'hom are currently on the disabled list. Is the Roberts camp regrouping? Downgrading? Or slip-sliding away?

When Team Roberts w^as great, it was truly great. From 1990 to ’92, it could do no wrong. Yet in less than three years, the team has fallen from grace. The story of how this happened is paved with glory and touched with tragedy.

This saga begins in 1984. Casting about for a post-racing career after his epic championship defeat by Fast Freddie Spencer, Roberts hastily cobbled together a low-budget 250 team with production Yamahas, shoestring Marlboro backing and Briton Alan Carter riding alongside Roberts’ American protégé, Rainey. After a difficult year, the boss resolved that if he were to go racing again, it would have to be done properly, with the right budget and the right factory backing.

That came in 1986: Lucky Strike paintwork on full-works Yamaha 500s. Randy Mamola and Mike Baldwin won several races over the next two years, but Roberts had planned all along around Rainey, and the Californian was ready after taking his second U.S. Superbike title. Thus in 1988, Roberts and Rainey embarked on the business of GP racing in earnest, and the achievements of the mentor-protégé partnership were awesome.

In 1988, Rainey won a single 500cc grand prix. In 1989 he won three, and was just pipped for the title by old sparring partner Eddie Lawson after a rare race crash in Sweden.

Then, from 1990 through 1992, with the team now swaddled in Marlboro colors, Rainey pretty much owned the joint. He was the guy to beat for a crop of high-class racers such as former champions Lawson

and Wayne Gardner and future champions Kevin Schwantz and Mick Doohan. John Kocinski, another Roberts protégé, devastated the 250cc GP ranks in 1990-further proof of> The Empire’s invincibility.

The Team Roberts establishment grew and grew. Computer men joined dyno men joined middle managers joined development men. By this time, Roberts was a great racing guru. Far-sighted and quick-witted, he filled the role well. And among his pearls of wisdom, he publicly lambasted the Yamaha factory for its lack of development on the works YZR500. “We’re trying to make this bike better, and we’re not getting the backup,” Roberts would complain, in between threatening to switch to Honda, Suzuki and Cagiva forthwith.

A top-level management change at Yamaha meant that Roberts’ requests fell on increasingly deaf ears. Roberts relates, “I’d say to Wayne that the worst thing we could do was to keep on winning. When we’d complain (about lack of development), Yamaha would say, ‘What are you bitching about? You’re winning!”’

In 1993, the complaints had real substance. A wrong turn in chassis development made the first half of the year an uphill struggle. Only when Rainey switched to a French-made ROC chassis mid-season did things turn around. With his hallmark determination, the triple world champion pulled himself back into a narrow points lead ahead of old rival Schwantz before he crashed while leading that fateful Italian GP and severed his spinal cord. The blow was felt throughout racing, and Roberts, Rainey’s closest friend as well as team owner, was heartbroken. Likewise, the rest of the team. Cadalora’s biggest problem was with the Dunlop tires. A long-standing penchant for the Anglo-Japanese rubber has at different times been the team’s major weakness and its greatest strength. Rainey loved them for their controllability while sliding. For> Cadalora, they were only bad and he eventually forced an embarrassing midseason switch to Michelins in 1995.

Over the next two years, Team Roberts never really recovered. All the while, erratic results and internal arguments were presided over by an increasingly glum Roberts.

One problem was the lack of a top rider, as if anybody could replace the inspiration and strength that Rainey possessed. The task fell to Luca Cadalora, and while the Italian won six races in three years, it was a patchy affair at best, with as many retirements or bad finishes when Cadalora “didn’t feel right.” This was a new and baffling complaint for Roberts.

There were angry scenes between Roberts and his rider, and it was inevitable that they would split at the end of the year. By then, K.R was glad to put it all behind him. In retrospect, he says, “People assumed there was a clash of personalities, but it wasn’t so much that. Luca just did his own thing. I liked that when he was riding with Wayne. But when Wayne left and Cadalora took over leading the team, it wasn’t so good.”

Even before the end of the ’95 season, Roberts had become so disillusioned that he considered quitting. “I didn’t like the way things were going,” he says. “It just seemed like a no-win situation and I was always caught in the middle: Yamaha had one thing, Marlboro wanted to win, the riders were complaining about the bikes and tires. It was kind of a helpless feeling. It got to the point where the easy way out was to sell the whole team.”

The plan didn’t come off, and details remain sketchy, but it is known that Rainey was a potential buyer, and it’s thought that Marlboro may have stepped in to prevent the deal. Roberts is uncharacteristically coy about details. He simply says, “In the end, I just wasn’t able to do it.”

The season ended in mass confusion. Roberts and Marlboro had a contract for 1996, but Roberts didn’t have a winning rider. After much negotiation to steal World Champion Mick Doohan from Honda, the Australian opted to stay put. British World Superbike Champion Carl Fogarty swam in and out of the frame. A reconciliation with the estranged Kocinski seemed the obvious solution, but negotiations broke down when Marlboro balked at hiring this extremely talented yet loose-lipped smoking gun.

In the end, though both Rainey and Roberts deny the scenario, it seems Marlboro decided what would hap pen. The tobacco giant already had its own contracted riders: Italian ex-125 double world champion turned 250 star Loris Capirossi would go to Rainey; Jean-Michel Bayle would go to Roberts. Yamaha, meanwhile, insisted that Roberts retain Japanese boy-wonder Norifumi Abe for a second season. Roberts got what he wanted with a third place on the team for his son, Kenny Jr.

This still leaves a major dilemma. While not short of talent, Marlboro doesn’t have a real 500cc title hopeful. This is surely an uncomfortable position for the biggest backers of GP racing, whose last 500 crown came with Rainey in 1992. And while they might have to tolerate this for ’96, they will surely want to be winning again next year.

This inevitably throws Roberts and Rainey into direct competition for the coveted Marlboro money and works Yamahas again for 1997. Rainey has the advantage of focus. He has just one 500cc rider, Capirossi, who is in his second year on a 500 after an enthusiastic debut last season on a Honda. Rainey also retained former world champ Tetsuya Harada in the 250cc class. This has the makings of a highly effective team.

Roberts freely acknowledges that winning the title this year would be a miracle, and that a race win would be reason to celebrate. He cautiously says, “We’ll do better than people think, but not as well as I'd like.”

Abe will probably finish on the ros-> trum a few times during the year; Bayle is a long shot. Early tests showed that the former French MX hero’s style of playing with power and wheelspin are better suited to 500s than the 250s he has ridden for the past three years. That is, until he crashed in Malaysia during pre-season testing. Fortunately, he wasn’t seriously hurt.

This leaves Junior. The eldest Roberts boy is firmly cast in the Rainey role. Big boots for a kid with just one full 250 season behind him. But Junior is a quick learner and trusts his father implicitly. He says, “My dad is always ahead of everyone in the ball game of racing. He tells me what I need to do, and I do it. I never second-guess him.” During pre-season testing, Junior brought the mighty YZR500 in under the lap record at Albacette, Spain, but he also left the team’s Malaysia test session with a broken leg after crashing. Fuckily, the break was expected to heal before the first race in March.

The senior Roberts suggests that neither rider would have crashed on the Dunlop tires the team was using last season. “We’re still trying to dial the suspension and powerband to suit our new Michelins,” he says. He also concedes that these things happen: “Sitting on one of those things at the limit, crashing is inevitable. We must create an atmosphere where all hell doesn’t break loose at once.”

Still, Junior now must justify the family fast-track that has allowed him to bypass all those tiresome years of winning national championships be-> fore getting a top works 500.

Coming off admittedly tough times, Roberts looks toward the 1996 season with guarded enthusiasm. “They’re not in Doohan’s class yet, but then again, they haven’t been riding 500s for five years. We need to spend some time improving our bike and building up new riders,” Roberts says.

Of course, if you were in charge of a multimillion-dollar budget and three riders with a grand total of zero GP wins between them-one of whom is sidelined with broken bones-that would be your company line, too. But don't lose faith in the renegade who revels in adversity. Things may look bleak for Team Roberts at the moment, but remember, you can’t keep a good dynasty down for long.