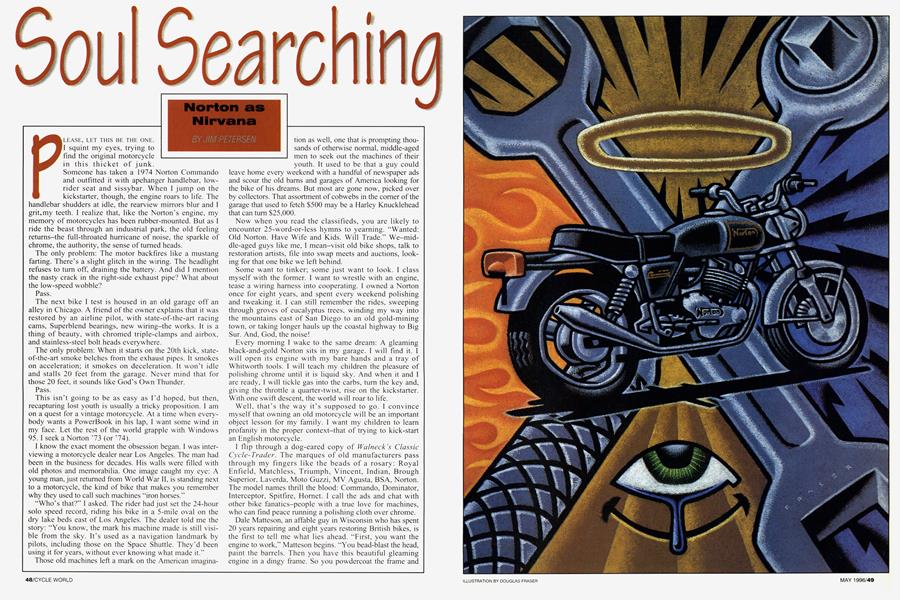

Soul Searching

Norton as Nirvana

JIM PETERSEN

PLEASE, LET THIS BE THE ONE. I squint my eyes, trying to find the original motorcycle in this thicket of junk.

Someone has taken a 1974 Norton Commando and outfitted it with apehanger handlebar, lowrider seat and sissybar. When I jump on the kickstarter, though, the engine roars to life. The handlebar shudders at idle, the rearview mirrors blur and I grit.my teeth. I realize that, like the Norton’s engine, my memory of motorcycles has been rubber-mounted. But as I ride the beast through an industrial park, the old feeling retums-the full-throated hurricane of noise, the sparkle of chrome, the authority, the sense of turned heads.

The only problem: The motor backfires like a mustang farting. There’s a slight glitch in the wiring. The headlight refuses to turn off, draining the battery. And did I mention the nasty crack in the right-side exhaust pipe? What about the low-speed wobble?

Pass.

The next bike 1 test is housed in an old garage off an alley in Chicago. A friend of the owner explains that it was restored by an airline pilot, with state-of-the-art racing cams, Superblend bearings, new wiring-the works. It is a thing of beauty, with chromed triple-clamps and airbox, and stainless-steel bolt heads everywhere.

The only problem: When it starts on the 20th kick, stateof-the-art smoke belches from the exhaust pipes. It smokes on acceleration; it smokes on deceleration. It won't idle and stalls 20 feet from the garage. Never mind that for those 20 feet, it sounds like God’s Own Thunder.

Pass.

This isn't going to be as easy as I’d hoped, but then, recapturing lost youth is usually a tricky proposition. I am on a quest for a vintage motorcycle. At a time when everybody wants a PowerBook in his lap, I want some wind in my face. Let the rest of the world grapple with Windows 95. I seek a Norton ’73 (or ’74).

I know the exact moment the obsession began. I was interviewing a motorcycle dealer near Los Angeles. The man had been in the business for decades. His walls were filled with old photos and memorabilia. One image caught my eye: A young man, just returned from World War II, is standing next to a motorcycle, the kind of bike that makes you remember why they used to call such machines “iron horses.”

“Who’s that?” I asked. The rider had just set the 24-hour solo speed record, riding his bike in a 5-mile oval on the dry lake beds east of Los Angeles. The dealer told me the story: “You know, the mark his machine made is still visible from the sky. It’s used as a navigation landmark by pilots, including those on the Space Shuttle. They'd been using it for years, without ever knowing what made it.”

Those old machines left a mark on the American imagination as well, one that is prompting thousands of otherwise normal, middle-aged men to seek out the machines of their youth. It used to be that a guy could

leave home every weekend with a handful of newspaper ads and scour the old bams and garages of America looking for the bike of his dreams. But most are gone now, picked over by collectors. That assortment of cobwebs in the corner of the garage that used to fetch $500 may be a Harley Knucklehead that can turn $25,000.

Now when you read the classifieds, you are likely to encounter 25-word-or-less hymns to yearning. “Wanted: Old Norton. Have Wife and Kids. Will Trade.” We-middle-aged guys like me, I mean-visit old bike shops, talk to restoration artists, file into swap meets and auctions, looking for that one bike we left behind.

Some want to tinker; some just want to look. I class myself with the former. I want to wrestle with an engine, tease a wiring harness into cooperating. 1 owned a Norton once for eight years, and spent every weekend polishing and tweaking it. I can still remember the rides, sweeping through groves of eucalyptus trees, winding my way into the mountains east of San Diego to an old gold-mining town, or taking longer hauls up the coastal highway to Big Sur. And. God, the noise!

Every morning I wake to the same dream: A gleaming black-and-gold Norton sits in my garage. I will find it. I will open its engine with my bare hands and a tray of Whitworth tools. I will teach my children the pleasure of polishing chrome until it is liquid sky. And when it and 1 are ready, I will tickle gas into the carbs, turn the key and, giving the throttle a quarter-twist, rise on the kickstarter. With one swift descent, the world will roar to life.

Well, that’s the way it’s supposed to go. I convince myself that owning an old motorcycle will be an important object lesson for my family. I want my children to learn profanity in the proper context-that of trying to kick-start an English motorcycle.

I flip through a dog-eared copy of Walneck’s Classic Cycle-Trader. The marques of old manufacturers pass through my fingers like the beads of a rosary: Royal Enfield, Matchless, Triumph, Vincent, Indian, Brough Superior, Laverda, Moto Guzzi, MV Agusta. BSA, Norton. The model names thrill the blood: Commando, Dominator, Interceptor, Spitfire, Hornet. I call the ads and chat with other bike fanatics-people with a true love for machines, who can find peace running a polishing cloth over chrome.

Dale Matteson, an affable guy in Wisconsin who has spent 20 years repairing and eight years restoring British bikes, is the first to tell me what lies ahead. “First, you want the engine to work,” Matteson begins. “You bead-blast the head, paint the barrels. Then you have this beautiful gleaming engine in a dingy frame. So you powdercoat the frame and paint the tank. Then you realize the chrome doesn’t look so good ...” Asked to explain his devotion, Matteson says simply, “I just like to hear ’em coming down the road.” My own devotion picks up speed with every motorcycle I read about. Soon I am attending shows. My first one is at the World Gym in downtown Chicago. AÍ Phillips, the 57-

The meeting has the air ofa 12-step recovery session: "Hi, I'm Fred, and I have a `72 Interstate. Black."

year-old owner, crashed a Norton when he was a kid. Physical rehabilitation became a passion; so did motorcycles. His gym is filled with immaculately restored classics-a green Nimbus from Denmark, a couple of Nortons, a Vincent, an MV Agusta. Over the row of bikes a sign proclaims, “It’s not the age; it’s the condition that counts.” It is a sentiment that fits both bike and body.

I watch Phillips ride a sidecar through the parking lot; he’s as joyful as a teenager. I walk past rows of Harleys and a spiffy BSA Victor. The show reflects the two trends in restoration; One camp throws away everything that was stock and replaces it with chromed aftermarket jewelry. The other camp takes junkers and restores them to mint condition. A third camp simply shows up on the same bike they bought 20 years ago-a display of fidelity that has its own weight. No one at this show wants to part with his machine, but someone gives me a card with directions to the Chicago Norton Owners Association.

The club meets on the first Wednesday of every month at a dark-paneled pizzeria on the southwest side. The meeting has the air of a 12-step recovery session. Meetings begin with new members introducing themselves: “Hi. I’m Fred, and I have a ’72 Interstate. Black.” And every meeting ends with a tech session. Like parenting, the problems of owning an old motorcycle are common.

They show me modifications-replacing leaky old Amals with efficient Mikunis, quaint points with a BoyerBrandsen electronic ignition-and pass along their secrets. One guy shows me how to clear a carburetor using the high E-string of a guitar. Another swears that the only way to judge a bike is by the feel of the clutch lever. Soon I am surreptitiously fondling clutch levers on every bike in the parking lot.

Club members are all in their mid-40s. Over shared pizza and beer, they tell of rides taken on their bikes. They are time travelers. One had visited a swap meet of steamengine owners and speaks of watching someone shovel sawdust into a firebox, sending showers of sparks into the night air. Even now, weeks later, he is ecstatic.

None of them want to sell their bikes (most have two or three), but I have a fine evening anyway. More determined than ever to find my own true bike, I start Commando shopping in earnest.

One afternoon I find myself at Motorcycle Enterprises, an understated cinder-block building, its walls lined with mufflers and exhaust pipes like the tusks of extinct animals; shelves filled with gas tanks awaiting paint and emblems; tables filled with carburetors, brake cables, pistons, rubber pegs. Two mechanics are wrestling a cylinder head free from a Triumph frame. They strike me as cowboys at a calfing. I walk down a line of bikes, noting those that are beyond repair, caressing those that are beyond my budget.

Marshall Hagy, the owner, troubleshoots a Triumph that a customer has rolled in. Pulling out an Allen wrench, he removes a carb in seconds, points out the wear. The guy leaves his credit card number-with about a SI000 estimate for bringing the bike back to life. “It’s a 20-year-old bike,” Hagy says. “Things wear out.” Expensive things. But the cost to fix it will be worth it. There is a pride in preserving these symbols of man’s ingenuity. Some of us refuse to be a party to the disposable society, to fall prey to planned obsolescence. For these, the mania has the tinge of a moral obligation. For others, it is simply a return to the simple past, when all you needed to

know about motorcycle mechanics was gas, spark, air.

Hagy shows me an unmolested Commando with low mileage and an astronomical asking price. “You’re only original once,” he says.

Pass.

He suggests I go to the Woodstock Show, referring me to an annual swap meet held at a country fairground in McHenry County. “Bring money. The best stuff is gone by dawn,” he warns.

The next weekend. I’m there. Volunteers in orange vests waving fistfuls of $5 bills take my admission and point me to an open field. I wander through the vendor stalls. Ponytailed dealers sit behind tables on which cylinder heads are stacked like skulls. You name it, it's for sale: memorabilia, seats, exhaust pipes, pistons. The truly initiated can pick out a specific part in a glance, whether it’s a petcock or a 40-year-old gearshift lever.

Empty frames sit there with the quiet challenge of the crossword puzzle in The New York Times. Can you find all the parts you need to rebuild a legend? Dozens of classic bikes are for sale, but Hagy was right: The best, including a handful of Nortons, were sold by dawn. With the buying frenzy subsiding, I just thumb through old shop manuals while my son plays at a table filled with pressed-tin toy motorcycles.

In the main shed are the showbikes, restorations that sucked thousands of dollars out of the wallets of the wellto-do, or hours of loving care from hobbyists. Motorcycles as fine art. But, unlike paintings, these leak. 1 watch a grayhaired lady walk around putting out orange rectangles of paper to catch the oil dripping from primary cases.

The shed holds Indians with skirted fenders and gas tanks that speak of coachwork. Long-framed HarleyDavidsons seem to carry their engines in front of the rider like offerings. Tiny Whizzers-little more than bicycles with miniature motors-bring a smile.

If evolution is the imagination of God rising to the occasion, then motorcycles are the spirit of man rising to the challenge. I walk from bike to bike following ideas-how best to let an engine breathe, how to convey the power of that engine to the rear wheel, how to illuminate the highway, how to deal with rough road.

Is there a Holy Grail, one bike that everyone has heard of but no one has seen? Buzz Walneck thought so. For six and a half years he sought a picture of “The Roadog,” a VEight-powered motorcycle that was supposed to be the size of a locomotive. One day someone called and said, “Forget the photo-I know where the bike is.” Buzz bought the bike, all 4000 pounds of it.

I see Buzz at the show, surrounded by motorcycle nuts who want to pick his brain. When I reveal my obsession, he is completely understanding. A few days later he calls to tell me the whereabouts of a perfect black Norton.

It’s mine.

Jim Petersen is a senior staff writer and senior editor at Playboy. This is his first article for Cycle World.