The right map for the bike

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

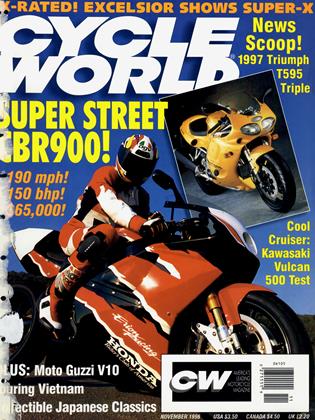

WITH CERTAIN MOTORCYCLES, THERE IS a defining moment when you know you are going to have to buy one, sooner or later. A gear suddenly locks to its shaft and the two spin as one, idea and destiny together.

That happened to me when I was at the Harley-Davidson plant in York, Pennsylvania, last fall, doing a story for Big Twin magazine, our all-Harleys sister publication. I spent an entire Sunday sitting down at the end of the motorcycle assembly line, interviewing H-D workers who build, ride and modify their own Harleys.

The assembly line had been shut down for the weekend on Saturday at noon, and the last bike on the conveyer was a Mystic Green and black Road King, missing only a few bits of hardware to be complete.

All day long I looked at the thing, letting it soak into my brain, much the way a strong Sauerbraten marinade works on chuck roast. Between interviews I would walk over and stand by it. By the end of the afternoon, a welder named Kevin “Smokey” Barley said, “I believe you better buy one of those.”

And I said, “I believe I will.”

Returning home, I ordered one from my local dealer, a gentleman named AÍ Decker, who, with his wife Mary, has run a Harley dealership for 50 years. The bike is supposed to be here in about three weeks, theoretically.

I bought essentially the same motorcycle from Al four years ago, a 1992 FLHS. Not much different from the current Road King, except that it had a plastic instrument pod left over from the Seventies and the optional “pillowlook” touring seat with little puckered buttons all over it. On the positive side, it had a better handlebar, a stock luggage rack, and was $4000 cheaper.

But the Road King is more like the bike I was looking for in the first place, a functional, modern antique with a slightly closer resemblance to an early Hydra-Glide Panhead, the standard by which I judge all American Twins. Anyway, the FLHS is gone; the King is coming.

Quite a few of my sport-riding buddies, of course, have suggested any number of desirable bikes I might buy for the same price-a fine collection of them, even. But nearly all duplicate in some way the sporting virtues of my

Ducati 900SS or my old Triumph 500. Which I already have.

What I miss having is a bike at the other end of the spectrum. A motorcycle for carrying two people and luggage across the vastness of America while exuding a certain historical charm and making great mortar-like thuds of combustion. The motorcycle equivalent of a Stearman biplane, if you will. For my money, nothing fills this bill better than a H-D Twin. Still.

Especially if you tweak about 20 more bhp out of its engine aftermarketwise, which I’m fixin’ to do toot-sweet upon delivery.

Anyway, I’ve noticed an interesting change in my life since I ordered the Road King: I’ve found myself looking at a whole different set of maps.

Big ones. National maps, with large, distant places like Kansas and New Mexico on them. It’s been a while.

Before taking a Sunday-morning ride on my Triumph 500, I tend to get out small maps. Usually from my highly detailed DeLorme Atlas of county maps, with lots of thin gray roads named Shady Hollow Lane or Dogbite Ridge. Short-range stuff.

I know people like our friend Ted Simon in Jupiter’s Travels went around the world on a Triumph 500, and there’s no reason not to if you don’t object to the extravagant consumption of pistons. But in my own mind, the Triumph T100-C was made for trails, farm roads and local exploration. Its

agile, lightweight talents are wasted on the big open highway; the meter is always running toward rebuild time.

On Ducati rides, a state map comes into play. On top of the Ducati’s tank bag I have a Wisconsin map, usually folded to one quadrant or another. If I get up early enough on the weekend, I’ll usually plan a trip of several hundred miles. As with the Triumph, you can obviously ride a 900SS farther than that, especially with à Corbin seat. In fact, I’m planning to j take mine to Sturgis next week.

Still, when you look at a 900SS in your garage, you don’t think of crosscountry travel. That’s not what it’s for. You can ride across Texas, but you don’t dream of riding across Texas.

And the Road King?

Here, all the state borders come tumbling down. The fine focus goes away (along with a little finesse) and you roll a big map of North America across the dining room table, like a Persian rug merchant showing his wares.

Suddenly you would pay good money and use valuable vacation time to ride to Texas, and then go all the way across it, just for fun. Visit your good friends in Blanco and Archer City, then drop down to Big Bend Park and maybe take in the Terlingua Chili Cookoff. No problem. America is at your feet.

As it should be. Most motorcycles, after all, have evolved to work best on their native roads.

Triumph 500s, for instance, may have won the Jack Pine Enduro here in the U.S., but I always feel they were actually built for a quick spin down a country lane between two small villages in the Cotswolds. Or a run to the pub.

Ducatis can cover a lot of ground anywhere, but they seem happiest in those pockets of the U.S. that most resemble the twisting mountain roads of Emilia Romagna or the open sweepers of Tuscany. It’s what they were bom to do.

And Harleys? To me, they seem to have been built with the Great Plains and deserts in mind...the American West. Big Sky bikes.

Thudding down some long, lonesome highway in Nebraska or Wyoming, you can easily imagine that Bill Harley long ago took one good look at the map of America, let out a low whistle and said, “We’re going to need bigger pistons. Two of ’em, with a slow, lazy heartbeat.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue