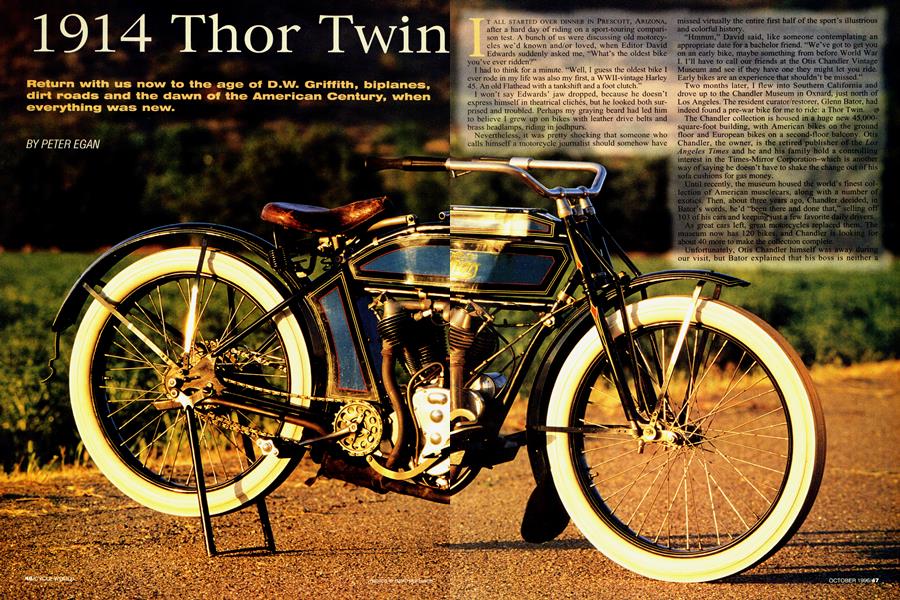

1914 Thor Twin

Return with us now to the age of D.W. Griffith, biplanes, dirt roads and the dawn of the American Century, when everything was new.

PETER EGAN

IT ALL STARTED OVER DINNER IN PRESCOTT, ARIZONA, after a hard day of riding on a sport-touring comparison test. A bunch of us were discussing old motorcycles we’d known and/or loved, when Editor David Edwards suddenly asked me, “What’s the oldest bike you’ve ever ridden?”

I had to think for a minute. “Well, I guess the oldest bike I ever rode in my life was also my first, a WWII-vintage Elarley 45. An old Flathead with a tankshift and a foot clutch.”

I won’t say Edwards’ jaw dropped, because he doesn’t express himself in theatrical clichés, but he looked both surprised and troubled. Perhaps my graying beard had led him to believe I grew up on bikes with leather drive belts and brass headlamps, riding in jodhpurs.

Nevertheless, it was pretty shocking that someone who calls himself a motorcycle journalist should somehow have missed virtually the entire first half of the sport’s illustrious and colorful history.

“Hmmm,” David said, like someone contemplating an appropriate date for a bachelor friend. “We’ve got to get you on an early bike, maybe something from before World War 1. I’ll have to call our friends at the Otis Chandler Vintage Museum and see if they have one they might let you ride. Early bikes are an experience that shouldn’t be missed.’

Two months later, I flew into Southern California and drove up to the Chandler Museum in Oxnard, just north of Los Angeles. The resident curator/restorer, Glenn Bator, had indeed found a pre-war bike for me to ride: a Thor Twin.

The Chandler collection is hnised inahuge new 45,000:, square-foot building, with American bikes on the ground floor and European hikes on a second-floor bal~ny. Ot~ Chandler, the owner, is the retired~puhlisher.~~~s Ange1e~ Timc,c and he and his family hold a cont~1hng interest in the Times-Mirror co~oration-whicb is another way of saving he doesn't have to shake the chan~e o*of his sofli cushions fbr gas money.

L Unt~14ticent1y, the museum housed tlic worId `s finest col 1~etion American musciecars, a1~J~ with a number of Then, about th~~ ago, handIer decided, fl: Bato~s wo~4~ he'd "b~there a~d done that," selling off. FGThf~us cars and ke~ii~ju$a tbw favorite dairy drivers

___ `5,' L'ctJ I As~reat cars at n `rcycIcs replaced theni~.Th~ nws~rn 2~ike nd ChandI~1s ook~ng5for about 40 rn~rc to make~e ctic r~p1~. -

Oti~~ñller himse~i our visit, t Bator explained that his boss is néiThe?~à novice nor a born-again motorcyclist.

“He’s had bikes all his life; rode a ’47 Knucklehead back and forth from Stanford to L.A. when he was in college, and has had an Indian Four for 20 years. Back in the Eighties, he rode a CBX a lot. He’s always loved motorcycles, and we’ve always had a few bikes here in the collection.”

And one of that collection was now the Thor. Bator wheeled it out of the lineup for me to look at. Sky blue and dark blue two-tone, with pinstripes of yellow and red. A thing of beauty and a survivor. From 1914, no less.

Is there anybody still alive who rode motorcycles in 1914? Any living person who remembers buying a brand-new Thor from his friendly dealer?

Can’t be many, and in a few years, we can safely say, there won’t be a single one: 1914 is getting to be a long time ago.

Let’s see... Woodrow Wilson was president of the United States when this bike was built. The airplane was only 11 years old. Across the sea, the inbred royal families of Europe were glaring at each other through monocles and pince-nez across tense borders, stewing in the hatreds and jealousies that would set off World War I in July of that very summer. Meanwhile, the most inept collection of generals the world has ever seen was preparing to murder an entire generation of young men. Who would never, ever get to ride motorcycles.

What had started off with such hope and optimism as the Century of Progress was just about to turn ugly.

Back in America, however, Progress was still the rule. Science and invention were setting us free from drudgery and isolation in this big, lonely continent. We had electric lights, flickering movies, telephones, mechanized farm equipment, Model-T Fords and motorcycles. Lots of motorcycles. More than 300 manufacturers participated in the great pre-war sales boom, though many were merely framebuilders using proprietary engines.

One of those engine builders was the Aurora Automatic Machinery Co. of Chicago, Illinois. They started out building single-cylinder Indian engines designed by the great Carl Oscar Hedstrom for the fledgling Hendee Manufacturing Co., which then lacked the necessary foundry to build its own. Soon, however, Aurora was building its own complete bikes, under the name Thor.

Their run on this Earth was relatively short (1903-1916), but Thor built some high-quality bikes, eventually developing a pair of V-Twins, of 61and 76-cubic-inch displacement, both well regarded for their quality and reliability by riders of the time.

Our bike here is the rarer A-Model Twin, the 9-horsepower 76-incher, built only in 1914. Original cost, $315.

This one has an interesting history in that it was formerly owned by Floyd Clymer, once the publisher of Cycle magazine. It was restored by a gentleman with the unusual name of Wilfred Foulstick in 1962. We don’t know who kept it alive before that.

In style and specification, the Thor is very similar to Indians and Harleys of the time, incestual engineering trends (the UJM, for example) being nothing new.

It has cylinders with a bore and stroke of 3.57 x 3.80 inches, arranged in a 50-degree Vee, with roller bearings on the big ends of the rods. Valves are set in the then-popular ioe (intake over exhaust), or F-head, pattern, the exhaust valves in the sides of the barrels and the intakes just above them in the cylinder heads. The intakes are operated by an external pushrod and rocker arm, which need to be hand-oiled from time to time. Internal engine oil is pumped from a tank on the seat downtube, and never returns—total loss. There’s also a small thumb-pump on the oil tank, to provide extra pressure for hard running.

A Bosch magneto sits just ahead of the cylinders, and the Scheibler carburetor nestles between the cylinders on the left side, above the enclosed clutch, which is operated by a fore-aft lever that you also have to twist to change gears. A drivechain transmits the 9 horsepower to a rear hub with a two-speed transmission and Bendix bicycle-style coaster brake.

Rear suspension? None, of course; it’s a hardtail. The front uses a rigid truss that contains thin internal springs, allowing a minute amount of travel on the leading links, which rock on a fulcrum and pull downward on the springs.

What we got here is a slightly elongated, beefed-up Schwinn paperboy bicycle (circa my 1950s youth) with a rectangular gas tank between the crossbars and a big honking V-Twin stuck in the frame. Every schoolboy’s dream. Time to ride.

Or, I should say, instruction time.

Bator went over the 19 steps needed to start and operate the bike, but I began to go deaf and blind at about Step 9. “Better write this down,” I said.

Here’s what yesterday’s rider had to do before dashing off to see Double Trouble with Douglas Fairbanks at the local cinema:

1. Put bike on rear stand.

2. Shove T-handled clutch lever all the way forward with left hand.

3. Turn T-handle straight ahead, parallel with tank, which is high gear (bike is too hard to start in low).

4. Pull in right-hand compression-release lever on handlebar.

5. Set throttle at about 1/4 open by turning LEFT twistgrip inward (no return spring, it stays where you leave it).

6. Turn RIGHT twistgrip clockwise, away from yourself to retard magneto advance.

7. Set choke by twisting a threaded disc in the carburetor throat.

8. Turn on fuel petcock under tank.

9. Turn on oil petcock (very, very important) on oil line at right rear of engine.

10. Stand up on pedals, push hard to get engine turning over.

11. Pedal like crazy.

12. When engine is spinning fast, let go of compression release lever.

13. When engine fires (you hope), pull clutch lever back into neutral.

14. Push backwards on bicycle pedal so Bendix brake stops the rear wheel from spinning.

15. Get off bike to roll it forward, then fold up rear stand.

16. Climb back on bike and roll on just enough throttle with left grip.

17. Tum T-handle clutch lever sideways for first gear and ease lever forward with left hand.

18. Make same left hand leap back to throttle for more gas, then back to clutch lever for more clutch, etc., until underway.

19. Adjust magneto advance to suit load and speed.

You are now rolling. To shift, you simply dial the throttle back (counterclockwise with left hand), pull backwards on the clutch lever, turn it sideways into top gear and shove it forward again.

Notice here that you need two left hands, yet the left foot does almost nothing, except pedal the starting crank. Luckily for us, many customers must have noticed this.

All this sounds worse than it is, of course, and makes perfect sense when you ponder the bike’s mechanicals. Nevertheless, I wrote all these instructions down, then sat on the bike for a few minutes, doing a dry run and trying to get it all straight in my mind. I didn’t want to hit the side of a parked car while staring at my hands and feet.

How did Thor dealers in 1914 explain all this to first-time buyers? They must have held MSF courses on the Bonneville Salt Flats to prevent collisions.

More likely, the people who bought motorcycles were a special breed, self-selected by mechanical instinct and a sense of adventure. They were the same people who learned to fly Curtiss Jennys after a couple of lessons—and survived. We always think older generations must not have been as smart and adept as we are, but it ain't true. They were like us, only more so, in some cases.

After several minutes of quiet, Zen-like info-soak, I figured I had it.

I set all the controls, stood up and pedaled like crazy. The bike started easily—on my second try, once I realized how furiously you have to pedal for momentum. It caught with a few random bangs and then settled down to a fairly steady ta-CHUFF-taCHUFF-ta-CHUFF beat at idle, with an undertone of syncopated strawsucking sounds from the carb throat. Nice engine note; mechanically pleasing and solid, without the clattering threat of self-destruction that hangs over some older powerplants.

Somehow you just know when a machine was built to stay running.

Off the stand, I eased the clutch forward and the Thor juddered away, onto some quiet industrial roads around the museum. Clutch back, handle sideways and into high gear.

Full magneto advance, both grips inward for Go, outward for Slow.

The old girl was surprisingly light and quick. Amazing what a favorable power-to-weight ratio will do for a vehicle, regardless of age. 1 immediately thought how thrilling a good motorbike like this one must have been to people reared on horses, passenger trains and early automobiles. Even then, bikes were right at the outer boundary of acceleration. For S3 15 you could outaccelerate almost any vehicle known to Mankind. Natural daredevil stuff.

Top speed, which we measured against a car because there's no speedometer, was clocked at about 50 mph, and still climbing slightly when we ran out of road. It'll probably do 55, but feels relatively undertaxed and mellow at 45 mph or so. Plenty fast for dirt roads full of chuckholes, ruts and chickens.

One thing the old girl wouldn’t do is turn. Or at least not very well.

Those sporty white 28 x 3-inch four-ply Universal tires look great but have perfectly square shoulders, so the bike wants to stand upright and flop off its knife-edges back onto the flat center section. Unless you hold a very firm hand on the tiller, the Thor goes all wonky and dippy in corners. A simple round bicycle tread, though not historically correct, would no doubt make it corner as nicely as that Schwinn I mentioned.

And those handlebars are interesting: about 1 8 inches of backsweep, with floppy rubber anti-vibration tips to save the hands on long rides. I didn't use them much. It's like trying to steer with a pair of folded dinner napkins. Otherwise. the bars are comfortable, given the seating position, and they work fine and feel elegant.

Stopping?

Well, think about how well your 1968 Triumph 500 stops (almost not at all), then subtract 54 years of scant progress. There’s no front brake, of course, and the rear works just as well as the coaster brake on your old bicycle-if you were carrying a full gas can and a big motorcycle engine for luggage. There’s a regular foot-operated brake on the right floorboard, connected by a lever to the pedal crank, but the pedals have to be in the right position (3 and 9 o’clock) for it to work, so you tend to simply use the bicycle pedals. Safer.

Coming to a stop, or avoiding an obstacle, takes a little time, not just because of the brakes, but because you have to shut the throttle down and then move your same left hand to the clutch lever, all the while backpedaling for retardation.

How anyone did this quickly enough to handle the ruts and nasty surprises of 1914 American roads is beyond me. Riders must have just gritted their teeth and held on. Or crashed through fences. The Thor is light and narrow, but it’s no snappy motocrosser. Everything happens with nautical deliberation, as in docking a boat.

Late in the afternoon, w^e loaded the Thor into a truck and hauled it up into the warm, sunny mountains to do photography and some more riding around the lovely town of Ojai.

After a few hours of riding, my brain finally switched over. I was riding the Thor and operating its odd controls almost without thinking about it. And the more 1 rode, the better I liked it. It's a charming, sturdy bike with a nice engine gait on the highway, a comfortable sprung saddle and a well-machined feeling to the controls. In some strange way, it reminded me of operating the old Kluge printing press in my dad’s shop. Solid levers doing forthright things.

By the time it got dark (no headlight) and we loaded the bike up to go home, I was ready to ride it across the country. Okay, maybe with some round-profile tires, but that’s all I'd need.

For all its age, the Thor is a real motorcycle, but it comes with the added entertainment of mechanical solutions that evolved before these things were set in stone. The rules had not been made yet and everything was open for consideration. You might operate the clutch by squeezing the gas tank with your knees, or accelerate by digging mechanical spurs into the engine cases. No one yet knew what would become the norm, and it's this learn-as-we-go element that makes you feel like part of the original motorcycle adventure.

But there’s another satisfying aspect, too.

Perhaps because it is so bicvcle-like, the Thor transports you back to that naive stage of your life when there was no greater joy than simply flying down the road in the wind without pushing on pedals or running on your own two feet. It is freedom from work combined with the freedom to travel. a heady combination. Your progress across the landscape seems like a small miracle, an escape from the plodding agricultural monotony of the 19th century, and all the centuries that came before. To ride the Thor is to remember the wonder of your first motorcycle ride, every time. Ö

View Full Issue

View Full Issue