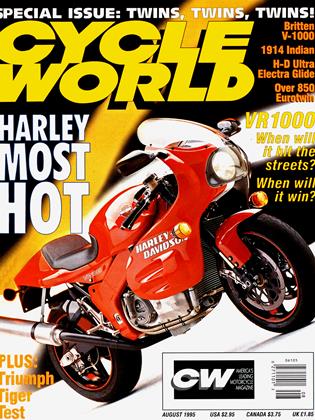

BRITTEN V-1000

LIFE ABOARD THE WORLD’S BEST V-TWIN

MARK FORSYTH

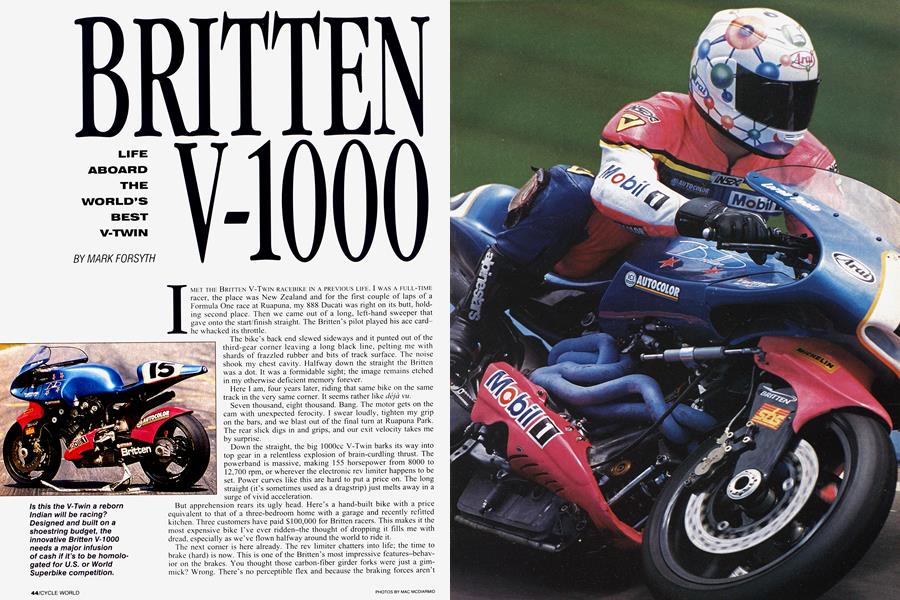

I MET THE BRITTEN V-TWIN RACEBIKE IN A PREVIOUS LIFE. I WAS A FULL-TIME racer, the place was New Zealand and for the first couple of laps of a Formula One race at Ruapuna, my 888 Ducati was right on its butt, holding second place. Then we came out of a long, left-hand sweeper that gave onto the start/finish straight. The Britten's pilot played his ace cardhe whacked its throttle.

The bike’s back end slewed sideways and it punted out of the third-gear corner leaving a long black line, pelting me with shards of frazzled rubber and bits of track surface. The noise shook my chest cavity. Halfway down the straight the Britten was a dot. It was a formidable sight; the image remains etched in my otherwise deficient memory forever.

Here I am, four years later, riding that same bike on the same track in the very same corner. It seems rather like déjà vu.

Seven thousand, eight thousand. Bang. The motor gets on the cam with unexpected ferocity. I swear loudly, tighten my grip on the bars, and we blast out of the final turn at Ruapuna Park. The rear slick digs in and grips, and our exit velocity takes me by surprise.

Down the straight, the big l000cc V-Twin barks its way into top gear in a relentless explosion of brain-curdling thrust. The powerband is massive, making 155 horsepower from 8000 to 12,700 rpm, or wherever the electronic rev limiter happens to be set. Power curves like this are hard to put a price on. The long straight (it’s sometimes used as a dragstrip) just melts away in a surge of vivid acceleration.

But apprehension rears its ugly head. Here’s a hand-built bike with a price equivalent to that of a three-bedroom home with a garage and recently refitted kitchen. Three customers have paid $100,000 for Britten racers. This makes it the most expensive bike I've ever ridden—the thought of dropping it fills me with dread, especially as we've flown halfway around the world to ride it.

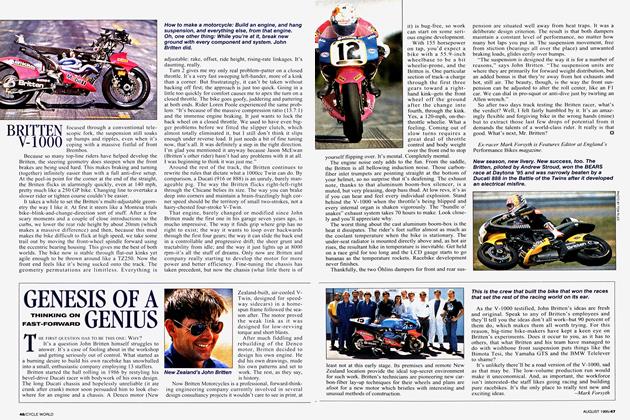

The next corner is here already. The rev limiter chatters into life; the time to brake (hard) is now. This is one of the Britten’s most impressive features-behavior on the brakes. You thought those carbon-fiber girder forks were just a gimmick? Wrong. There’s no perceptible ilex and because the braking forces aren't focused through a conventional telescopic fork, the suspension still soaks up bumps and ripples, even when it’s coping with a massive fistful of front Brembos.

Because so many top-line riders have helped develop the Britten, the steering geometry does steepen when the front brakes are being used hard. This makes braking and turning (together) infinitely easier than with a full anti-dive setup. At the peel-in point for the corner at the end of the straight, the Britten flicks in alarmingly quickly, even at 140 mph, pretty much like a 250 GP bike. Changing line to overtake a slower rider or tighten course couldn’t be easier.

It takes a while to set the Britten's multi-adjustable geometry the way I like it. At first it steers like a Montesa trials bike-blink-and-change-direction sort of stuff. After a few scary moments and a couple of close introductions to the curbs, we lower the rear ride height by about 20mm (which makes a massive difference) and then, because this mod makes the bike difficult to flick at high speed, we take some trail out by moving the front-wheel spindle forward using the eccentric bearing housing. This gives me the best of both worlds. The bike now is stable through flat-out kinks yet agile enough to be thrown around like a TZ250. Now the front end feels like it’s being sucked onto the track. The geometry permutations are limitless. Everything is adjustable: rake, offset, ride height, rising-rate linkages. It’s daunting, really.

Turn 2 gives me my only real problem-patter on a closed throttle. It’s a very fast sweeping left-hander, more of a kink than a corner. But frustratingly, it can’t be taken without backing off first; the approach is just too quick. Going in a little too quickly for comfort causes me to apex the turn on a closed throttle. The bike goes goofy, juddering and pattering at both ends. Rider Loren Poole experienced the same problem: “It’s because of the massive compression ratio (13.7:1) and the immense engine braking. It just wants to lock the back wheel on a closed throttle. We used to have even bigger problems before we fitted the slipper clutch, which almost totally eliminated it, but I still don’t think it slips enough under reverse load. It just needs a bit of fine tuning now, that’s all. It was definitely a step in the right direction. I’m glad you mentioned it anyway because Jason McEwan (Britten’s other rider) hasn’t had any problems with it at all. I was beginning to think it was just me.”

Around the rest of the track, the Britten continues to rewrite the rules that dictate what a lOOOcc Twin can do. By comparison, a Ducati (916 or 888) is an unruly, barely manageable pig. The way the Britten flicks right-left-right through the Chicane belies its size. The way you can brake deep into corners and maintain a brain-frazzlingly high corner speed should be the territory of small two-strokes, not a hairy-chested four-stroke V-Twin.

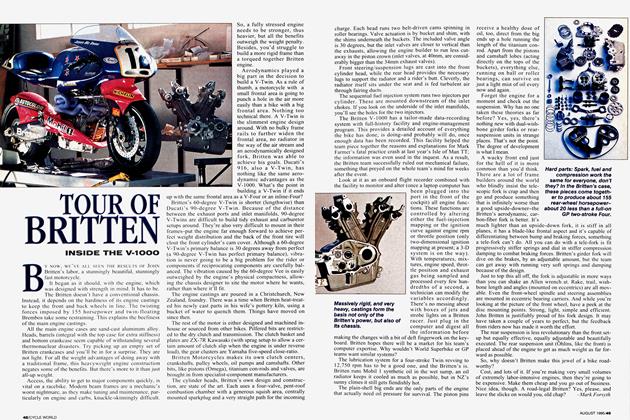

That engine, barely changed or modified since John Britten made the first one in his garage seven years ago, is mucho impressive. The way it finds grip where grip has no right to exist; the way it wants to loop over backwards through the first four gears; the way it can slide the back end in a controllable and progressive drift; the sheer grunt and tractability from idle; and the way it just lights up at 8000 rpm-it’s all the stuff of dreams. Only now are Britten and company really starting to develop the motor for more power and better efficiency. Fine-tuning the chassis has taken precedent, but now the chassis (what little there is of it) is bug-free, so work can start on some serious engine development.

With 155 horsepower on tap, you’d expect a bike with a 55.9-inch wheelbase to be a bit wheelie-prone, and the Britten is. One particular section of track-a charge through the first three gears toward a righthand kink-gets the front wheel off the ground after the change into fourth, through the kink. Yes, a 120-mph, on-thethrottle wheelie. What a feeling. Coming out of slow turns requires a great deal of throttle control and body weight over the front end to stop

yourself flipping over. It’s mental. Completely mental.

The engine noise only adds to the fun. From the saddle, the Britten is all bellowing induction noise. Those carbonfiber inlet trumpets are pointing straight at the bottom of your helmet, so no surprise that it’s deafening. The exhaust note, thanks to that aluminum boom-box silencer, is a muted, but very pleasing, deep bass thud. At low revs, it’s as if you can hear and feel every individual explosion. Stand behind the V-1000 when the throttle’s being blipped and every internal organ is shaken vigorously. The “bundle o’ snakes” exhaust system takes 70 hours to make. Look closely and you’ll appreciate why.

The worst thing about the cast aluminum boom-box is the heat it dissipates. The rider’s feet suffer almost as much as the coolant temperature when the bike is stationary. The under-seat radiator is mounted directly above and, as hot air rises, the resultant hike in temperature is inevitable. Get held on a race grid for too long and the LCD gauge starts to go bananas as the temperature rockets. Racebike development never finishes.

Thankfully, the two Öhlins dampers for front and rear suspension are situated well away from heat traps. It was a deliberate design criterion. The result is that both dampers maintain a constant level of performance, no matter how many hot laps you put in. The suspension movement, free from stiction (bearings all over the place) and unwanted braking loads, glides eerily over bumps.

“The suspension is designed the way it is for a number of reasons,” says John Britten. “The suspension units are where they are primarily for forward weight distribution, but an added bonus is that they’re away from hot exhausts and hot, still air. The beauty, though, is the way the front suspension can be adjusted to alter the roll center, like an FI car. We can dial in pro-squat or anti-dive just by twirling an Allen wrench.”

So after two days track testing the Britten racer, what’s the verdict? Well, I felt fairly humbled by it. It's an amazingly flexible and forgiving bike in the wrong hands (mine) but to extract those last few drops of potential from it demands the talents of a world-class rider. It really is that good. What’s next, Mr. Britten?

Ex-racer Mark Forsyth is Features Editor at England’s Performance Bikes magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOklahoma Hits Home

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGood Company

August 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThunder Bolts

August 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBritten To Build Indians

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupBikes Will Be Made In the Usa, Says Indian's New Chieftain

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart