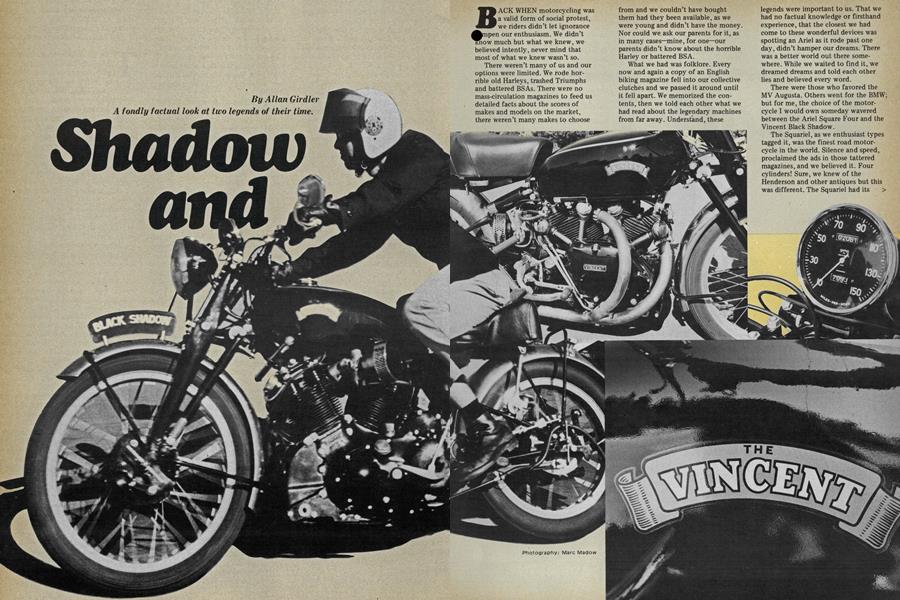

Shadow and Squariel

A fondly factual look at two legends of their time.

Allan Girdler

BACK WHEN motorcycling was a valid form of social protest, we riders didn’t let ignorance mpen our enthusiasm. We didn’t know much but what we knew, we believed intently, never mind that most of what we knew wasn’t so.

There weren’t many of us and our options were limited. We rode horrible old Harleys, trashed Triumphs and battered BSAs. There were no mass-circulation magazines to feed us detailed facts about the scores of makes and models on the market, there weren’t many makes to choose

from and we couldn’t have bought them had they been available, as we were young and didn’t have the money. Nor could we ask our parents for it, as in many cases—mine, for one—our parents didn’t know about the horrible Harley or battered BSA.

What we had was folklore. Every now and again a copy of an English biking magazine fell into our collective clutches and we passed it around until it fell apart. We memorized the contents, then we told each other what we had read about the legendary machines from far away. Understand, these

legends were important to us. That we had no factual knowledge or firsthand experience, that the closest we had come to these wonderful devices was spotting an Ariel as it rode past one day, didn’t hamper our dreams. There was a better world out there somewhere. While we waited to find it, we dreamed dreams and told each other lies and believed every word.

There were those who favored the MV Augusta. Others went for the BMW; but for me, the choice of the motorcycle I would own someday wavered between the Ariel Square Four and the Vincent Black Shadow.

The Squariel, as we enthusiast types tagged it, was the finest road motorcycle in the world. Silence and speed, proclaimed the ads in those tattered magazines, and we believed it. Four cylinders! Sure, we knew of the Henderson and other antiques but this was different. The Squariel had its > cylinders set in a square, with two crankshafts geared together. Smooth, compact, light and indestructible.

Ariel pioneered rear suspension when everybody else bolted the back wheel to the frame. The workmanship was superb, due to the lack of mass production and the devotion of the maker’s craftsmen. The Ariel abounded with clever devices and techniques beyond those of the average bikes.

The Black Shadow was something else. All it needed was one claim:

The Vincent Black Shadow was the fastest production motorcycle in the world. Right out of the box a Black Shadow would hit 150 mph. One, flaming five, flaming aught! Our vantage point, the fastest we had ever gone, was a good way below the magic ^rtury, and to do the ton and one I^P was beyond our comprehension if not our intentions. We knew why we had never seen a Black Shadow. They were illegal. They were so fast an ordinary person wasn’t allowed to buy one. Go ahead, snicker. Twenty years after those days the government won’t let us buy gasoline. You think this is the first generation to doubt the integrity of its leaders?

This magazine appeals to a wide variety of readers. There will be some who were experienced riders in those far-off days. There will be more who don’t remember a time when riding bikes wasn’t something every kid wanted to do. There may be readers who don’t believe the rumor that Soichiro Honda didn’t invent the motorcycle. We all, however, are slightly bananas over the same activity. It is this writer’s hope that the appeal of myth is universal, that when I say I was told of a man who owns both a Shadow and a Squariel, the reader will react as I did: Let’s go see those legendary bikes. What was the ultimate motorcycle of yesterday really like?

First, some history. Mind, I did this research in the recent past. The historical facts below were collected years after these machines were my favorite ambition. When I conjured up my myths, I knew nothing of this.

The Ariel Square Four was created by the affluent 20s. There was a market for the refined-if-expensive motorcycle. Most factories catered to this by replacing rough Singles with fancy Twins. Ariel went further. By using four pistons on two cranks rotating in opposite directions, Ariel came up with an engine much smoother than the opposition could offer. Power wasn’t the goal here. The first Square Four was 500ec, less than the factory offered in a Single or a Twin.

Such an elaborate engine required development time, and the Four wasn’t offered to the public until 1931. That was not a good time to offer an expensive motorcycle. The Squariel won a fine reputation. It was proclaimed the Rolls-Royce of motorcycles. Those lucky few who had the money for one were much admired by the majority who didn’t.

The good reputation was valued by the firm, and the model was treated to several series of improvements. The displacement was increased; first to 600cc and later to 1000. Alloy replaced iron here and there and the suspension and transmission were refined. The high point would seem to have been the Mk II, produced from 1949 until 1959, at which point the rising influence of Japanese lightweights caused the company to concentrate on its own smaller bikes. This was the wrong move, as it turned out. The public didn’t want copies of what other people were doing better. A Mk III was introduced and withdrawn and the last Ariel of any sort was made in 1965.

Vincent fact was based on the same theme as Vincent legend: speed. The founder was a WW I pilot who, after the war, built bikes for sporting young gentlemen like himself. He also won races. There were mergers and dull things like that, as well, but for us the Vincent story begins in 1934, when the firm introduced an excellent 500cc Single. Two years later they added another cylinder, making a lOOOcc VTwin. The model name was “Rapide,” and it would do 115 mph, making it the fastest production bike of its day.

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 71

After that, it was a matter of tuning. The Black Shadow was a modified Rapide. According to the handbook I have in my hand, the Rapide produced 45 bhp and the Black Shadow had 55 bhp, thanks to a higher compression ratio, different valve timing and larger carburetors. And—I am shocked to learn—target top speed for the Black Shadow was 125 mph.

The magic figure of my past came from the factory-fitted speedometer, which read to 150 mph, a practice not unknown in the present day. Or it may be we were confused by names. There was a racing version of the Black Shadow. It carried the name Black Lightning, had 70 bph and the factory rated it at 150 mph. It wasn’t sold as a road bike.

That’s how two of my legends began. The top speed was genuine, incidentally. A wealthy enthusiast bought a Black Lightning and took it to Bonneville, where it did 160. There is a classic picture of that, with the rider lying on the tank, flying across the salt at 160 mph in helmet and bathing suit. Yes, they changed the rules to require protective clothing shortly afterward.

Oh, and the 150-mph model was delivered with a 180-mph speedo. I don’t know why, or rather, I don’t want to know why.

Vincent, like Ariel, was better at making bikes than doing business.

There were sorties into small bikes and three-wheelers, even a water scooter, none of which did well. In 1954 the D model Rapide, with streamlining, in the form of fiberglas shells, was announced. A roadburner’s dream, as one writer put it. But the firm’s owners had lost enough money and the factory closed its gates in 1955.

Enough history. Our host on this occasion is Jim Schaeffer, owner of the Ariel and Vincent shown. His garage is full of parts. There are spare engines, frames, gas tanks, wheels and the like piled in corners and dangling from the walls. The Ariel parts, if assembled, would be a complete 1948 Square Four. And Schaeffer has, in three or four crates, another Shadow waiting for restoration. How, I wondered, did he get into this? >

Jim is 30, just old enough to have caught the tail ends of those legends mentioned earlier. He learned to ride on a borrowed BSA. When the t^^er moved, Jim decided to buy his own bike. A Triumph, he thought, and he was browsing in a Triumph showroom one day when the owner fired up a Squariel. “That did it. I knew I had to have one.”

He shopped around and bought a 1958 Mk II, in good condition except for various bits like the headlight nacelle and oil tank chrome-plated by a previous owner. Judicious trading turned up unplated parts, which he promptly fitted. For reasons of reliability, he added oil pressure and temperature gauges and a small oil cooler, the better to relax on long rides, which is what he does with the Ariel.

The Vincent was bought mostly on the strength of the legend. Jim had heard all those stories—in fact, I had forgotten about the illegal for public sale routine until he reminded me—and

too liked the sound of the stories.

Black Shadow is a 1953, model C.

He bought it in boxes, hauled them to a shop where Vincents are known and loved, and waited something like 18 months for everything to be checked and adjusted. The carbs are newer than the engine and he’s kept the slightly wider bars that were mounted when he bought the machine, but the Vincent, too, is basically as it came from the factory.

He hasn’t needed many parts, for which he’s thankful. There are active owner clubs and most of the owners know and help each other, but mostly, “It’s dog eat dog. If you find a part, you buy it, whether you need it or not.”

He imported the second Vincent from Holland of all places. He knows a guy who knows a guy who knew where fliis bike was sitting in a shed, so he ^ght it.

We’ll start with the Squariel, on the grounds that it’s the one I tried first.

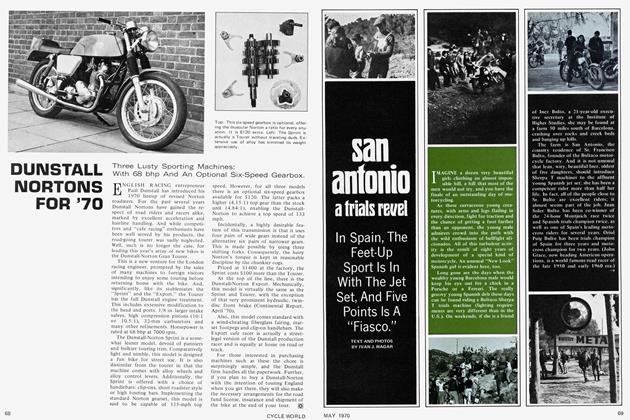

The bike looks, well, dated. Something about the shape of the tank, the wraparound fenders, the droop of the seat and the metal work blending headlight into front forks says the ‘50s. The engine is tidy, with the carb tucked under the tank and the four pipes sweeping down to a pair of mufflers. The welds on the pipes are beautiful. All the welds are beautiful.

One imagines that a good share of the cost of this machine was due to the high proportion of hand work, and to the nice touches here and there. The rear stand is a casting, for instance, polished and smoothed after it came from the mold. Even the spurs that hold the stand against the back of the frame

iere Jln’t shaped wish to just pay so. for Pity this the sort buyers of detailed finish.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 105

Front suspension looks normal. Rear suspension is distinctly odd. The frame is solid. The rear hub is sprung, via a pair of tubes that contain springs. The hub assembly moves up and down in a straight line at a right angle to the front sprocket, so the hub remains at the correct distance from the engine under extreme jounce and rebound. Ariel adopted this system back when lesser makes used solid hubs and Ariel stayed put.

The Squariel looks bulky. It isn’t.

Curb weight is about 450 pounds, or just about the same as that of a current BMW. And it feels on the small side, perhaps because the bars are narrower and the seat farther forward and lower than is the practice today.

Operation is no problem. Turn the key, set the choke, kick the lever and brooom, it’s running. The exhaust note is not the slightest bit refined. It’s the ragged, rolling bark of a small, highly-tuned Four. Just what you’d expect and just what you wouldn’t expect, so to speak. A pleasant sound, anyway, if most unRollsish. The foot shift is on the right and requires a certain firmness, presumably because in those days the only way to make a gear strong was to make it big. The clutch lever is surprisingly light.

Off we go, then, everthing feeling normal. The Squariel is geared for normal road use; i.e. a mixture of traffic and open road. England didn’t have a speed limit when this bike was built and the country was famous for its smooth roads. At the same time, England had no superhighways. Normal country riding was done at less than breakneck speds on good pavement that curved a lot.

In consequence, this model is quite nice in town. The engine smooths out (and quiets down) right off idle.

First gear is on the low side and starts are easy. The bike steers well and is well balanced for low speed maneuvers. The suspension is in keeping with the intent of the maker, as the rear spring arrangment, odd though it may appear, seems to do an adequate job of easing the blows from road imperfections. A big hole nearly cracks one’s spine, but then this motorcycle is not supposed to be ridden over bad holes. They have no business being there!

Got a little struggle going over the description of the engine. Runs fine. Plenty of power. Sound and feel, though, are vintage and I don’t know how to clarify that. The Square Four doesn’t hum; it throbs, with a rhythmic surging this rider has never experienced > before. At least not with a motorcycle. A friend of mine used to have a vintage speedboat with an engine that sounded and felt exactly the same. I have no explanation for this and can only say that the Ariel Square Four sounds and feels like a good old engine.

The Squariel is not a high speed motorcycle. Oh, no doubt it will do the 110 mph the factory claimed, but the rider will not be comfortable. The brakes are distinctly vintage and require a lot of effort for minimum retardation. They are small drums, one per wheelstate of the art for the late ‘40s. Few makers did much better than this.

The rider was expected to make allowances and plan ahead. So they did, one assumes.

High speed cornering is shaky. The rear suspension seems to allow the wheel to tilt, as cornering forces push one of those little springs higher than the other. Understand, one doesn’t look down and back to watch this interesting action, so that’s a guess. But that’s what it feels like and even the owner prefers to cruise through turns without a lot of leaning and derring-do. This is not to compare the bike to present designs. Consider it an observation.

The Squariel is much happier on today’s superhighway, at today’s 55 mph. The ride is nice, the upright riding position is fine, since there isn’t much wind to lean against, and the grooved tires don’t react at all to those confounded rain grooves in the pavement. The Ariel Square Four is a bike to be ridden at one’s leisure.

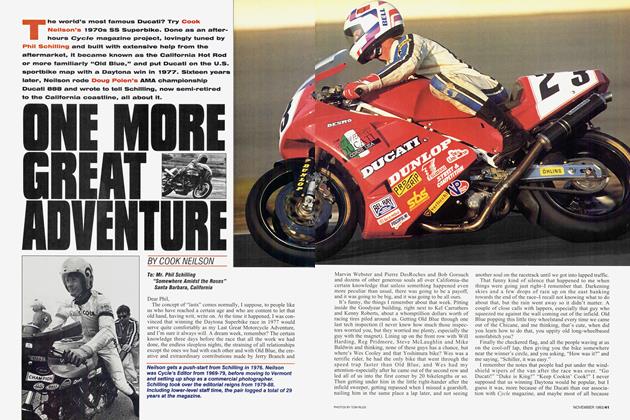

Merely looking at the Vincent sends a shiver down one’s back. Henry Manney once wrote that the Harley KH was the most randy motorcycle ever made.

So it was. On the same theme, the Vincent looks like a desperado. Not evil, not malevolent, just tough. Lean. Muscular and not adverse to displays of power. If the Black Shadow was a person, it would be the sort of guy who buys tight T-shirts and rips the seams with bulging biceps.

Yes, it’s an old bike. The fenders and tank, the odd seat and front forks make its age undeniable. But how strong it looks, despite its age. The glistening black crankcase bulks beyond the frame. The barrels bristle with fins and tubes; the airhorns jut past the tank.

The exhaust pipes, chrome-blued by years of heat, sweep out of the engine and down one side, almost rippling with power as they go. The men who put this engine into this frame did it with whip and chair.

Mechanical details are different, even unique. The front hub is solidly mounted to the forks, which in turn are sprung on the frame by sort of a cantilever arrangement. If the Ariel had a swinging rear hub, then the Vincent has a swinging rear frame. The back half of the diamond, so to speak, is cut loose from the front half. At the bottom, just aft of the transmission, there’s a pivot. At the top, below and behind the seat, a short section of frame has been replaced by three canisters, two with springs and one with a shock absorber. Not modern, obviously, and not an especially good arrangement, what with so much of the weight being unsprung. But it was a selling point back then.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 107

Vincents were club racing bikes and the factory did its share with technical work, if not hard cash. The brakes are drums, but they’re big, and there are two per wheel. Pit stops, anyone? The hubs aren’t held by normal nuts. Instead there are T-handles, so the rider or crew can remove the wheels and fix flats (or even change gearing) without wrenches. The seat is cushioned by some manner of dampening device, so mysterious in technique that the owner has never dared mess with it. The seat is dampened right for him, he says, why tamper with a good thing?

One myth I never heard, never having even known a guy who knew a guy who’d so much as seen a Black Shadow, was that the beasts are hard to start.

It’s no myth. A lOOcc Twin was mighty big in those days. To enable an average person to kick it over, the kick starter is geared low, that is, one kicks a long distance to turn the engine over maybe twice. A matter of leverage. Because one can’t count on spins, one must make each spin count. The proper technique: open the petcock, tickle each float bowl, check the switch to be sure the magneto is hot. Do not touch the throttle. Haul in the compression release. Right, the compression release. Kick down with all possible vigor. When the lever has traveled twothirds of the way, let go of the compression release. If this is done correctly, if one piston gets compression at just the right place in its cycle, the engine fires.

Or so they say. According to the literature, which makes mock of the rumors about hard to start, even a spindly schoolmarm can do it if she goes about it properly. Perhaps. Speaking firsthand, all an agile and determined novice will get for his trouble is an occasional backfire and the sneers of the crowd. Jim says it’s a knack. He said this all day, each time he had to start the bike for me. Then we had to do a little dance around the thing, keeping the engine alive while swapping place. No, the engine doesn’t idle well. How did you guess?

Sure runs good. The clutch is heavy and the gearing is long, as it must be with a redline of 6000 rpm and a target speed of 125 mph. Getting off the mark takes a healthy twist of the throttle and a good amount of clutch slip. The gear ratios are widely spaced, so one winds the engine up before dropping into the next speed. Shifts work best with a slow and heavy foot. The books say the Vincent gearbox was designed to transmit 200 bph. That means big wheels, as mentioned earlier.

The exhaust note is like that—dare I say it?—of a Harley. Go ahead, purists, take offense. Honest, it sounds like a Harley, which is also, bear in mind, a big V-Twin. The difference is that the Harley of that era had what?—35 honest horses and 1000 pounds to propel. The Black Shadow had 55 bph and 450 pounds. This was not a test, so no times were taken, but the magazines of the day spoke of 13-second quarters. It would take a pretty good new super bike to dust off this old warhorse.

On the open road, the Black Shadow is a delight. The ride is rough but stable. The machine swoops through corners with no wobble or hop, assuming the pavement is as smooth as it’s supposed to be. The feeling is one of unlimited power. Crank it on and the Vincent seems to lower its head, gather its haunches and flatten itself against the road.

The bike may be better than the times, as the 55-mph limit means that if the rider tries to use the Black Shadow as its makers intended, he risks fine and censure, albeit not life and limb. At 55 the Ariel is content; the Vincent is virtually unemployed.

At low speeds it feels top-heavy.

And, in town and traffic, alas, the Black Shadow is work.

The reader has no doubt discerned that this was a good day. If the facts are important—why should they be?— even an aging romantic will admit there’re a score of modern bikes as comfortable as the Ariel and as fast as the Vincent. One calls that....progress.

Take that, dreams of youth? Not quite. There was a basis for those myths, overblown though they were.

The Squariel and the Shadow wefe worthy of admiration then, and so they remain.

My concern is for the youth of today. Who can dream dreams and swap lies when all of the details and specifications and dyno readings are a matter of public record? There is no way the novice can avoid learning all the facts about the super bikes of today.

Where are tomorrow’s classics going to come from? Kl

Dirty old motorcycles need love too.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

JULY 1974 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

JULY 1974 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

JULY 1974 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

JULY 1974 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Fiction

Fiction"I'll Be Home In Time For Dinner."

JULY 1974 1974 By Arthur L. Frank -

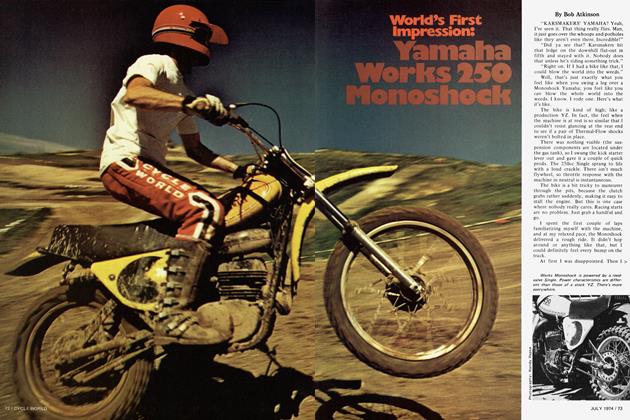

Special Preview

Special PreviewYamaha Works 250 Monoshock

JULY 1974 1974 By Bob Atkinson