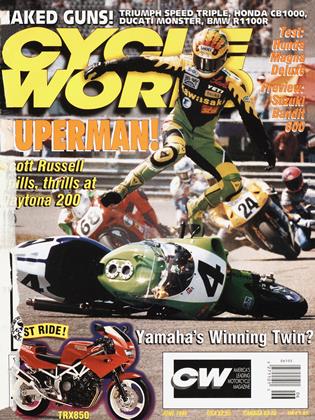

Daytona DNF

HIGH BANKS, HIGH ANXIETY

KEVIN CAMERON

ROAD TEST EDITOR DON CANET LOST THE FRONT END of his Team Cycle World/Attack Performance Yamaha YZF Superbike on lap four of the Daytona 200, and crashed out of the race in Turn One. As he had done a year ago, Don showed that he could run in fast company. He was behind eventual ninth-place finisher Donald Jacks when he crashed.

Why do magazines go racing? Certainly, the spirit of Walter Mitty lives in ail of us. We wonder what it would be like to pilot an F-16, to perform brain surgery, to be a star performer in any difficult and glamorous undertaking. But there is more than this. Magazine editors live with motorcycles professionally, riding them, testing them, describing their qualities. What gives us the authority to do this? Yes, we have years of experience, but we all know that this isn’t enough. Like Daytona, magazine writing has its classic traps-and the major one is formulaic writing: “Controls fall readily to hand...Seat padding was firm without being harsh...Vibration bothered some testers....” Magazine writing at its best can be a letter from one enthusiast to another, but it can also become just a job, a process of filling in the blanks. That has to be avoided.

Therefore, it’s essential periodically to leave the calm and status of the office and explore new territory where we are anything but experts. There, we do our best to learn the ropes, and then take the consequences. Racing, like having children, shakes us up, forces us to rethink everything, and mixes a useful amount of humility into our authority as motor-journalists. It rejoins us with our readers, most of whom are not experts either. And it’s fun-something that professional racers often forget.

We fell into some of Daytona’s traps, and avoided others. We did violate the prime rule of Daytona racing: Always run last year’s set-up, and avoid novelty. Because of this, our bike and crew arrived after the first practice day was over, and the team had to use more valuable practice time in completing details. This, of course, raises the anxiety level of even the most experienced riders. Hardware is essential, but software-the rider’s internal preparation to ride the event-is even more important. Don preserved his unique flat affect well, but the situation must have pumped him full of adrenaline that he had no way of burning.

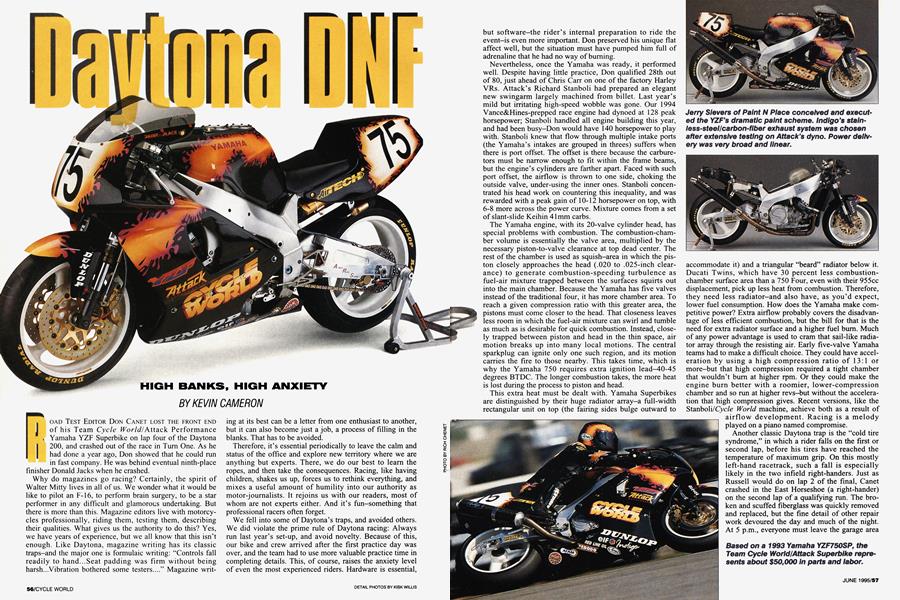

Nevertheless, once the Yamaha was ready, it performed well. Despite having little practice, Don qualified 28th out of 80, just ahead of Chris Carr on one of the factory Harley VRs. Attack’s Richard Stanboli had prepared an elegant new swingarm largely machined from billet. Last year’s mild but irritating high-speed wobble was gone. Our 1994 Vance&Hines-prepped race engine had dynoed at 128 peak horsepower; Stanboli handled all engine building this year, and had been busy-Don would have 140 horsepower to play with. Stanboli knew that flow through multiple intake ports (the Yamaha’s intakes are grouped in threes) suffers when there is port offset. The offset is there because the carburetors must be narrow enough to fit within the frame beams, but the engine’s cylinders are farther apart. Faced with such port offset, the airflow is thrown to one side, choking the outside valve, under-using the inner ones. Stanboli concentrated his head work on countering this inequality, and was rewarded with a peak gain of 10-12 horsepower on top, with 6-8 more across the power curve. Mixture comes from a set of slant-slide Keihin 41mm carbs.

The Yamaha engine, with its 20-valve cylinder head, has special problems with combustion. The combustion-chamber volume is essentially the valve area, multiplied by the necessary piston-to-valve clearance at top dead center. The rest of the chamber is used as squish-area in which the piston closely approaches the head (.020 to .025-inch clearance) to generate combustion-speeding turbulence as fuel-air mixture trapped between the surfaces squirts out into the main chamber. Because the Yamaha has five valves instead of the traditional four, it has more chamber area. To reach a given compression ratio with this greater area, the pistons must come closer to the head. That closeness leaves less room in which the fuel-air mixture can swirl and tumble as much as is desirable for quick combustion. Instead, closely trapped between piston and head in the thin space, air motion breaks up into many local motions. The central sparkplug can ignite only one such region, and its motion carries the fire to those nearby. This takes time, which is why the Yamaha 750 requires extra ignition lead-40-45 degrees BTDC. The longer combustion takes, the more heat is lost during the process to piston and head.

This extra heat must be dealt with. Yamaha Superbikes are distinguished by their huge radiator array-a full-width rectangular unit on top (the fairing sides bulge outward to accommodate it) and a triangular “beard” radiator below it. Ducati Twins, which have 30 percent less combustionchamber surface area than a 750 Four, even with their 955cc displacement, pick up less heat from combustion. Therefore, they need less radiator-and also have, as you’d expect, lower fuel consumption. How does the Yamaha make competitive power? Extra airflow probably covers the disadvantage of less efficient combustion, but the bill for that is the need for extra radiator surface and a higher fuel bum. Much of any power advantage is used to cram that sail-like radiator array through the resisting air. Early five-valve Yamaha teams had to make a difficult choice. They could have acceleration by using a high compression ratio of 13:1 or more-but that high compression required a tight chamber that wouldn’t bum at higher rpm. Or they could make the engine burn better with a roomier, lower-compression chamber and so run at higher revs-but without the acceleration that high compression gives. Recent versions, like the Stanboli/Cyc/e World machine, achieve both as a result of airflow development. Racing is a melody played on a piano named compromise.

Another classic Daytona trap is the “cold tire syndrome,” in which a rider falls on the first or second lap, before his tires have reached the temperature of maximum grip. On this mostly left-hand racetrack, such a fall is especially likely in the two infield right-handers. Just as Russell would do on lap 2 of the final, Canet crashed in the East Horseshoe (a right-hander) on the second lap of a qualifying run. The broken and scuffed fiberglass was quickly removed and replaced, but the fine detail of other repair work devoured the day and much of the night. At 5 p.m., everyone must leave the garage area after much haranguing by the Speedway’s scooter-mounted Men in Blue. Everything needed for the evening’s work must be hastily tossed in the truck for the trek to American Motorcycle Institute’s shops, kindly made available to all. Daytona all day, AMI all night.

The race engine had arrived headless, a short-block needing a lot of assembly. Saturday is Supercross day (no roadrace practice), and Stanboli turned wrenches to complete the race engine on a building stand as assistant Dean Vincent and Indigo’s Richard Moore pulled the practice unit from the chassis. Kit YZF con-rods are titanium forgings, but they gleam like gold because of their nitride surface coating. Cosworth 13.3:1 compression pistons work in stock iron sleeves. Last year, the Cycle World bike had suffered blown head gaskets, but there was no such trouble this time, thanks to effective measures taken by Stanboli.

Four-stroke engines have too many parts to be built at trackside (another Daytona syndrome: Let’s take our stuff to the racetrack and see if we can build a bike out of it), but Stanboli was putting in a virtuoso performance.

Roadracing constantly presents a terrible question: Are you

IN or are you OUT? If you are IN, it means doing everything you can to get on that start linearound the clock on coffee, aspirin and fast food, mechanically completing one task, then the next, then the next, seemingly forever. If you are OUT, it means real food for the stomach, a pillow for the head, but nothing at all for the spirit. We know that the best Daytona engines are built in the home shop in calm daylight hours-but a few good ones have also been finished moments before final tech. Stanboli finished ours and it ran well.

But the engine ate up hours that might have prepped the trick carbon-fiber gas tank. In the first test, it leaked at the seams. More adrenaline stabbed into our collective gut. The tank was daubed internally with aircraft slushing sealer and set aside to dry. When all else was ready on Sunday morning, it leaked again. The leak was contained-but not the adrenaline flow it had stimulated. Now we were close.

Pit-wall territory is staked out on Sunday morning by filling it with equipment. Somewhere down towards the desirable far end, sandwiched in between big teams with their blue and yellow gas drums, their compressors, generators and spare wheels hot in fitted electric blankets, was a thin slice for Team Cycle World. There you could find editors in their garish, once-a-year team bowling shirts. Yamaha had 26 men in new blue-and-white uniforms, Muzzy/Kawasaki had 12, Ducati Corse and Team Fcrracci their legions. We had six.

The final preparations get made. The tank is filled with ELF race fuel, reeking noticeably of fashionable methyl tertiary butyl ether. The tires are aired up. Hands fidget with details. Rider, machine and mechanics go to the grid to hear a quavering performance of the national anthem. The grand theater of warm-up lap, reassembly on the grid, confusion of people and machines, and the countdown to the flag brings us to the great noise and rushing-away of the start.

For us it was, as they say, all for naught. After surviving our own poor state of preparation, our novelties of construction, our crash damage, there was still one more classic disaster to come. Don would crash in Turn One on lap four. He was not the only crasher in this star-studded, excitementovercharged 200. Scott Russell would crash on the cold side of his tires on L2, then remount, dramatically run down the leaders from 56th place, and win. Former 200 winner Miguel Duhamel would lose the front end in Tum One. GPstar-turned-Harley-rider Doug Chandler only made two laps before sliding out in Turn 5. Former winner Jamie James would fall on L25. Hard-riding Australian Anthony Gobert, who ran second to Russell for many laps on another Muzzy Kawasaki, would fall on L48, as the final battles for position heated up. Good company, bad result.

No, we didn't get what we’d hoped for, which was to see Don Canet and the Team Cycle World Yamaha achieve the top-10 finish that seemed to wink elusively at us from a shimmering sea of possibility a year ago. We came away with a list of future good resolutions (we w ill arrive on time at the circuit with a running motorcycle...we will not push on the right sides of cold tires...we will not out-trick ourselves).

And, finally, in addition to whatever fun we all may have had, we reaped a rich harv est of humility.

SUPPLIERS

AFAM USA, INC. 5953 Engineer Dr. Huntington Beach, CA 92649 714/379-9040 Rear sprockets: $59/each Countershaft sprockets: $28/each

AIR TECH 2530 Fortune Way Vista, CA 92083 619/598-3366 Fairing upper: $375 Fairing lower: $231 Seat: $197 Front fender: $86 Airbox: $547 Carbon-fiber fuel tank: $1119

ARAI HELMETS P.0. Box 9485 Daytona Beach, FL 32120 RX-7RR helmet: $545

ATTACK PERFORMANCE 12929 Telegraph Rd., Unit G Santa Fe Springs, CA 90670 310/903-7757 Adjustable triple clamps: $595 Footpeg brackets: $285/pair Attack Rapid System billet swingarm and drive: $6,675 Data acquisition system: $3616 Cylinder head porting: $1500 Engine prep & assembly: $1800 (labor only)

BARNETT TOOL & ENGINEERING 9920 Freeman Ave. Santa Fe Springs, CA 90670 310/941-1284 Clutch: $144

BATES LEATHERS 3700 N. Industry Ave., #102 Lakewood, CA 90712 310/426-8668 Custom race leathers: $1365

DUNLOP TIRE CORP. P.0. Box 1109 Buffalo, NY 14240 800/828-7428 Front tires: $160 each Rear tires: $235 each

ELF USA P.0. Box 2026 Mission Viejo, CA 92690 800/353-3835 Leaded race fuel: $15/gal.

FERODO AMERICA 3529 Old Conejo Rd., Unit 102 Newbury Park, CA 91320 805/376-9565 Brake pads: $28/caliper

INDIGO SPORTS 12407 Slauson Ave. Unit B Whittier, CA 90606 310/945-8149 Race exhaust system: $627 Custom fit brake-line kit: $150 Aluminum bolt kit: $193 Titanium bolt kit: $450 Dzus fairing fasteners: $5 each

LINDEMANN ENGINEERING 520 McGlincey Ln. #3 Campbell, CA 95008 408/371-6151 Fork modification: $290

LOCKHART PHILLIPS USA 151 Calle Iglesia San Clemente, CA 92673 714/498-9090 Dainese Set gloves: $100 Alpinestars GP Pro boots: $249

NGK SPARK PLUGS USA INC. 8 Whatney Irvine, CA 92718 714/855-8278 Sparkplugs: $24/each

NOLEEN RACING, INC. 16276 Koala Rd. Adelanto, CA 92301 619/246-5000 Steering damper: $323 Rear shock: $777

PAINT N PLACE 847 S. Kraemer Placentia, CA 92670 714/630-6326 Custom paint: $1500 Custom helmet paint: $200

RACING ENGINE COMPONENTS 205 Johnson Weslaco, TX 78596 210/968-7802 Cosworth pistons: $789

RED LINE SYNTHETIC OIL CORP. 3450 Pacheco Blvd. Martinez, CA 94553 800/264-7958 Motor oil: $8 qt. Water wetter: $8/bottle

REGINA USA, INC. P.0. Box 109 Cambridge, MD 21613 410/221-2800 Racing chain: $100

SLATER BROTHERS P.0. Box 1 Mica, WA 99023 509/924-5131 Brembo front rotors: $590/pair Brembo Goldline calipers: $490/pair Brembo front master cylinder: $395

TARGA ACCESSORIES INC. 21 Journey Aliso Viejo, CA 92656 714/362-2505 Windscreen: $40

WORKS STAND 945 Camelot Dr. Crystal Lake, II 60014 815/455-6800 Bike stand: $249

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDoin' the Wave

June 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDucks Unlimited

June 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAlloy Connection

June 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBandits Coming Soon To Your Neighborhood

June 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Surprise Single

June 1995 By Robert Hough