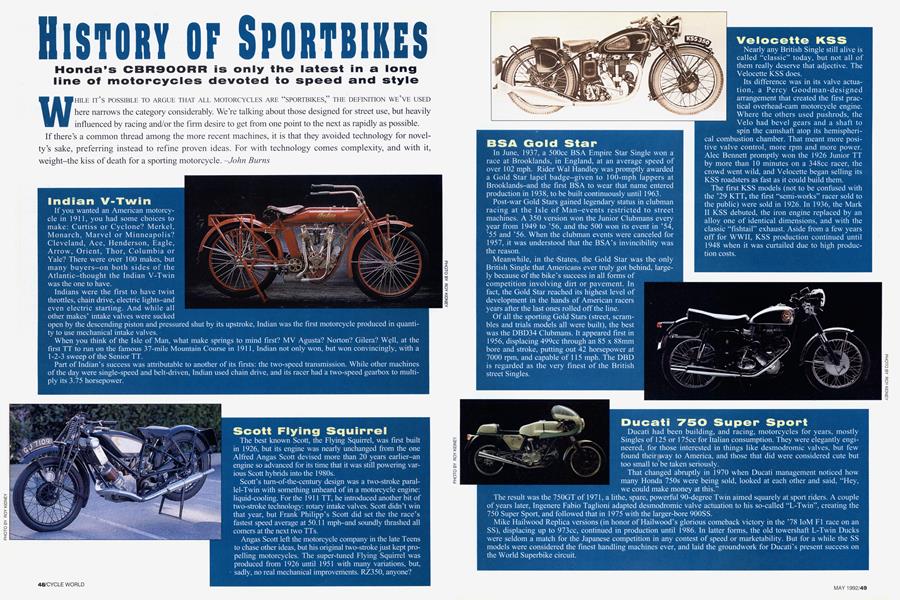

HISTORY OF SPORTBIKES

Honda’s CBR900RR is only the latest in a long line of motorcycles devoted to speed and style

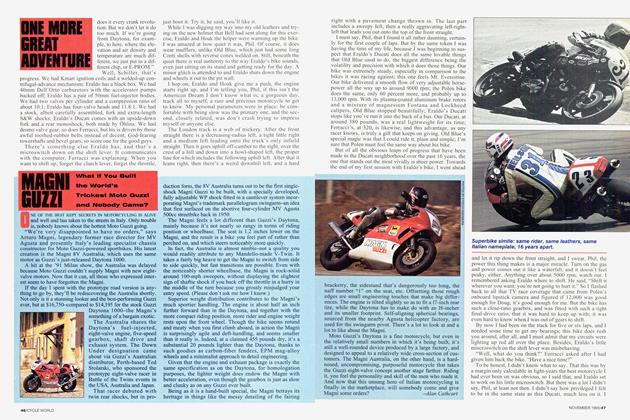

WHILE IT’S POSSIBLE TO ARGUE THAT ALL MOTORCYCLES ARE “SPORTBIKES,” THE DEFINITION WE’VE USED here narrows the category considerably. We’re talking about those designed for street use, but heavily influenced by racing and/or the firm desire to get from one point to the next as rapidly as possible. If there’s a common thread among the more recent machines, it is that they avoided technology for novelty’s sake, preferring instead to refine proven ideas. For with technology comes complexity, and with it, weight-the kiss of death for a sporting motorcycle.

John Burns

Indian V-Twin

If you wanted an American motorcycle in 1911, you had some choices to make: Curtiss or Cyclone? Merkel, Monarch, Marvel or Minneapolis? Cleveland, Ace, Henderson, Eagle, Arrow, Orient, Thor, Columbia or Yale? There were over 100 makes, but many buyers-on both sides of the Atlantic-thought the Indian V-Twin was the one to have. Indians were the first to have twist throttles, chain drive, electric lights-and even electric starting. And while all other makes’ intake valves were sucked

open by the descending piston and pressured shut by its upstroke, Indian was the first motorcycle produced in quantity to use mechanical intake valves. When you think of the Isle of Man, what make springs to mind first? MV Agusta? Norton? Gilera? Well, at the first TT to run on the famous 37-mile Mountain Course in 1911, Indian not only won, but won convincingly, with a 1-2-3 sweep of the Senior TT. Part of Indian’s success was attributable to another of its firsts: the two-speed transmission. While other machines of the day were single-speed and belt-driven, Indian used chain drive, and its racer had a two-speed gearbox to multiply its 3.75 horsepower.

Scott Flying Squirrel

The best known Scott, the Flying Squirrel, was first built in 1926, but its engine was nearly unchanged from the one Alfred Angas Scott devised more than 20 years earlier-an engine so advanced for its time that it was still powering various Scott hybrids into the 1980s.

Scott’s tum-of-the-century design was a two-stroke parallel-Twin with something unheard of in a motorcycle engine: liquid-cooling. For the 1911 TT, he introduced another bit of two-stroke technology: rotary intake valves. Scott didn’t win that year, but Frank Philipp’s Scott did set the the race’s fastest speed average at 50.11 mph-and soundly thrashed all comers at the next two TTs.

Angas Scott left the motorcycle company in the late Teens to chase other ideas, but his original two-stroke just kept propelling motorcycles. The super-tuned Flying Squirrel was produced from 1926 until 1951 with many variations, but, sadly, no real mechanical improvements. RZ350, anyone?

Velocette KSS

Nearly any British Single still alive is called “classic” today, but not all of them really deserve that adjective. The Velocette KSS does. Its difference was in its valve actuations,a Percy Goodman-designed arrangement that created the first practical overhead-cam motorcycle engine. Where the others used pushrods, the

Velo had bevel gears and a shaft to spin the camshaft atop its hemispherical combustion chamber. That meant more positive valve control, more rpm and more power. Alec Bennett promptly won the 1926 Junior TT by more than 10 minutes on a 348cc racer, the crowd went wild, and Velocette began selling its KSS roadsters as fast as it could build them.

The first KSS models (not to be confused with the ’29 KTT, the first “semi-works” racer sold to the public) were sold in 1926. In 1936, the Mark

II KSS debuted, the iron engine replaced by an alloy one of identical dimensions, and with the classic “fishtail” exhaust. Aside from a few years off for WWII, KSS production continued until 1948 when it was curtailed due to high production costs.

BSA Gold Star

In June, 1937, a 500cc BSA Empire Star Single won a race at Brooklands, in England, at an average speed of over 102 mph. Rider Wal Handley was promptly awarded a Gold Star lapel badge-given to 100-mph lappers at Brooklands-and the first BSA to wear that name entered production in 1938, to be built continuously until 1963.

Post-war Gold Stars gained legendary status in clubman racing at the Isle of Man-events restricted to street machines. A 350 version won the Junior Clubmans every year from 1949 to ’56, and the 500 won its event in ’54, ’55 and ’56. When the clubman events were canceled for 1957, it was understood that the BSA’s invincibility was the reason.

Meanwhile, in the States, the Gold Star was the only British Single that Americans ever truly got behind, large-

ly because of the bike’s success in all forms of competition involving dirt or pavement. In fact, the Gold Star reached its highest level of development in the hands of American racers years after the last ones rolled off the line.

Of all the sporting Gold Stars (street, scrambles and trials models all were built), the best was the DBD34 Clubmans. It appeared first in 1956, displacing 499cc through an 85 x 88mm bore and stroke, putting out 42 horsepower at 7000 rpm, and capable of 115 mph. The DBD is regarded as the very finest of the British street Singles.

Ducati 730 Super Sport

Ducati had been building, and racing, motorcycles for years, mostly Singles of 125 or 175cc for Italian consumption. They were elegantly engineered, for those interested in things like desmodromic valves, but few found their way to America, and those that did were considered cute but too small to be taken seriously.

That changed abruptly in 1970 when Ducati management noticed how many Honda 750s were being sold, looked at each other and said, “Hey, we could make money at this.”

The result was the 750GT of 1971, a lithe, spare, powerful 90-degree Twin aimed squarely at sport riders. A couple of years later, Ingenere Fabio Taglioni adapted desmodromic valve actuation to his so-called “L-Twin”, creating the 750 Super Sport, and followed that in 1975 with the larger-bore 900SS. Mike Hailwood Replica versions (in honor of Hailwood’s glorious comeback victory in the ’78 IoM F1 race on an SS), displacing up to 973cc, continued in production until 1986. In latter forms, the old towershaft L-Twin Ducks were seldom a match for the Japanese competition in any contest of speed or marketability. But for a while the SS models were considered the finest handling machines ever, and laid the groundwork for Ducati’s present success on the World Superbike circuit.

Moto Guzzi V7 Sport

When Lino Tonti took over as chief engineer at Guzzi in the late Sixties, one of the bikes he inherited was the V7, a lackluster-some said agricultural-touring motorcycle with a 90-degree Twin taken from a military tractor. In creating a silk purse from that sow’s ear, Tonti’s first move was to remove the large generator from between the cylinders, replacing it with a Bosch alternator at the end of the crankshaft (thus placing it at the front of the longitudinally mounted engine),

and clearing the way for a long, low frame with its backbone nestled down tightly between the cylinders. The new frame was triangulated for increased rigidity, had a shorter wheelbase for quick handling, and a well-supported steering head carrying Guzzi’s own telescopic fork. The military chuffer of an engine was taken to 748.8cc (just legal for 750cc racing) via bore and stroke of 82.5 x 70mm, compression was raised to 9.8:1, hotter cams and 30mm Dell'Ortos were fitted, and Moto Guzzi had built its first superbike—and an oil-tight, reliable, smooth and comfortable one at that. Largely handbuilt from ’72 through ’74, the V7 Sport was so popular in Italy that few found their way abroad. Later would come the bigger LeMans series, which Moto Guzzi did export successfully, but none were as purposeful as the original V7 Sport.

Norton John Player Special

This rare Commando, circa 1975, is less remarkable for what it is than for what it represents. While manufacturers had long recognized the value of racing success as a marketing tool, the JPS Norton was the first modern street motorcycle to come right out and be an unsolicited racer-replica, with no provision toward utility or passengers With its full fairing, twin headlights, clip-on bars and swoopy paint scheme, the bike looked just like the factory racers, and never mind that beneath all that fiberglass lay the same old Commando Twin. Riders interested in cafe had to build their own, and the foundation had been poured for the modem sportbike of the 1980s.

BMW R90S

When people started building motorcycles like the Honda CB750 and Kawasaki Z-l-bikes that ran fast and far reliably, and kept their oil inside the crankcases-they were brazenly treading on BMW’s turf.

Normally conservative, BMW opened up with both barrels and created the 898cc R90S in 1973. With a top speed approaching 125 and dual disc brakes up front, the biggest Boxer could run with the other superbikes of the era all day, comfortably. Reg Pridmore even used a modified R90 to take the U.S. Superbike title in 1976.

The R90S was uncharacteristically beautiful, too, with a café-style fairing and smoked paint. Even at the then-astronomical price of $3430, BMW sold every one exported to America, further proving that

speed and style often lead to show-room success.

Kawasaki GPz550

By 1981, the somewhat perorative term “UJM” had been coined to deal with the fact that transverse four-cylinder Japanese motorcycles had become as common as lawyers’ bellybuttons, and that one four-cylinder Japanese bike was largely indistinguishable from any other.

So Kawasaki took its KZ550 (new the year before, and very well received), grafted on twin disc brakes and a bikini fairing up front, hotted up the engine with more cam and compression, worked out better

and adjustable suspension, mixed up a batch of red paint, and rediscovered how many of us would spend money for a fast, sporty, lightweight, inexpensive motorcycle.

Honda V45 Interceptor

The 1983 Interceptor was the first bike to house a thoroughly modern engine in a cutting-edge chassis purpose-built for sporting use. Honda’s new V-Four had been seen the previous year, in the Sabre and Magna, but both those bikes relied on frame designs that were little changed from the days of Norton’s Featherbed. For the Interceptor, Honda pulled out the stops and built a steel perimeter frame that looked almost identical to the aluminum one on Freddie Spencer’s then-current GP Honda.

With this rigid frame came a steep steering-head angle and top-shelf suspension components-including a rising-rate-

linkage, single-shock rear end-making the new Honda the finest handling streetbike ever. As if that weren’t enough, the 16-valve, liquid-cooled V-Four was by far the most powerful engine in its class. With the Interceptor 750, the Japanese served notice that sportbikes were moving into a new era.

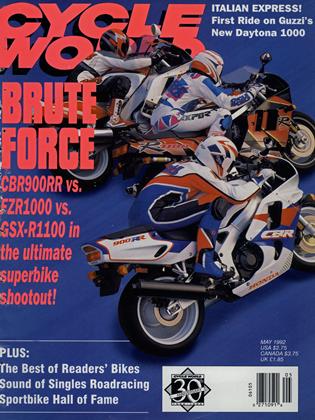

Kawasaki 900 Ninja

In 1984, Kawasaki countered Honda’s interceptor with the company’s first liquid-cooled, 16-valve bike, the Ninja 900. Its introduction marked the opening salvo in the upcoming superbike wars.

While its chassis may not have been quite as advanced as the Interceptor’s, the Ninja’s 908cc inline-Four was more than a match for Honda’s V-Four. Here was a motorcycle capable of nearly 150 mph.

Interestingly, the first Ninja’s design brief could’ve described the 1992 Honda CBR900RR’s-to build a bike the size of a 750, with the power of a liter-bike. As such, the Ninja was a screaming success.

Suzuki GSX-R750

Sportbikes continued to evolve, inch by inch, closer to racebikes, until, in 1986, a balance point was reached and there was the GSX-R-not so much a racified streetbike as a streetified racebike.

With a contemporary though not stunningly powerful engine, the GSX-R achieved overwhelming performance through tactics proven effective on genuine race machinery—by paring off, gram by milligram, every extraneous bit and piece until nothing was left but the necessary. As an example, the GSX-R’s aluminum-alloy frame weighed just 18 pounds.

The result of this mechanical diet was an overall weight much lighter than the competition’s. Combined with low clip-ons and rear-set footpegs, the GSX-R was racier than most racebikes, and an instant hit on the track and in the showroom. Low-mass was a resounding success. So why does the latest GSX-R750 weigh 60 pounds more than the original?

Obviously, Honda asked that question when it came time to build the CBR900RR. Honda knows how to do “complex” better than anyone, but seems to have taken the less-is-more lesson to heart with its new 900. Computer-aided design has even allowed Honda to add a new chapter to the history of the sportbike; now, every nut and bolt can be pared to the minimum without need for the decades of trial and breakage that resulted in the machines listed here. It will be interesting to see how the other manufacturers respond.