SPEED DEMON

Or how I learned to quit worrying and love the Stomper

JOHN BURNS

WHERE CAN YOU find a little history in Southern California? Let’s see, there’s the Los Angeles Cathedral, but it opened like five years ago. The hovel I inhabit in one of Orange County’s oldest towns was built way back in the Fifties. Mid-century, they call it. I’m toying with the idea of turning it into something like Historic Williamsburg, starting my own tourist trap. We’ll dress in period costume. I see myself in Bermuda shorts on a plaid Sears couch, watching “Howdy Doody” on a small black-and-white TV with rabbit ears, drinking Schlitz from a steel can with two church-keypoked holes in top while tourists from Teterboro file through behind the velvet ropes. When it happens, Jane will thank me for not remodeling the kitchen.

The point is, no wonder today’s youth are so alienated. There’s no frame of reference for the kids anymore. Here in SoCal, we got no Old North Churches, no Gettysburgs, no Watergate Hotels even. It’s all In-N-Out Burgers and auto malls and Levitra commercials. Extended families take the form of ex-wives and nannies from Jalisco. Listen pal, if my Granddad was around, you wouldn’t think that pierced nose was so cool; he’d have clipped his watch chain to it and given a stiff yank.

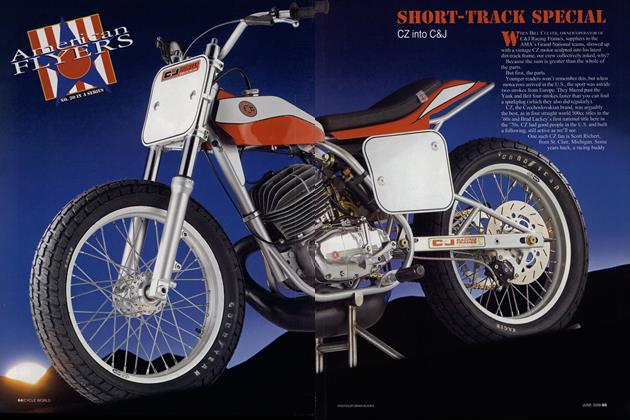

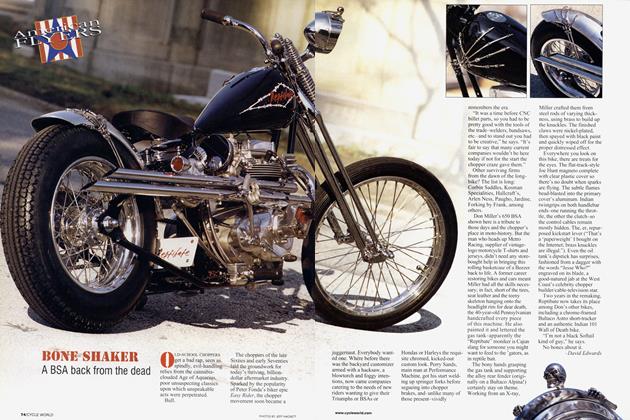

American FLYERS

Then there’s the general slipshoddiness and slapdashery of modem life. The constant unfolding of new scandal in the Information Age, the Terminator as Governor, the potholes, the failing school system, the ongoing inability to learn anything from history in spite of the unprecedented access, the terrible strain of knowing you are as noth-

ing since your ’04 R6 does not have an inverted fork. Space Shuttles falling from the sky are now a bigger menace than Soviet ICBMs, and don’t worry about them anyway, since we’ve almost got all the bugs out of our missile-defense system-all we have to do now is get one to fire. My favorite TV show is “American Hot Rod,” which chronicles the weekly adventures of famous hot-rod builder Boyd Coddington and crew. This’ll be great, I thought, watching and leaming from skilled artisans of the Old School, for whom painstaking craftsmanship really is Job One. What a joke. Boyd and his crew are more dysfunctional than the CIA, and job one episode after episode is slapping outsourced components together in time for some car show. Job two is firing people.

Even Hoyer, who doesn’t own a Ty and who actually seems to know how to build things, can’t turn away: “I can’t believe he ’s going to MIG that! ” Marky freaks.

Is there no sanctuary from modem capitalism?

And if that’s not all depressing enough, I had this story about Roland Sands’ ridiculous chopper hanging over my head, though I would seem to have been the natural choice to ride Valentino Rossi’s Yamaha a few issues ago.

If you looked up “punk” in the dictionary, there would be Sands. Tattooed, impish, Generation Whatever and exhibiting little in the way of respect for his elders. The last time I saw Roland, he was sliding off the infield at California Speedway in Fontana on a Yamaha TZ250, having passed me in a completely disrespectful manner half a lap or so earlier. Obviously the kid doesn’t know the value of a dollar, I thought, but then again he did win the AMA 250cc GP Championship in 1998, so maybe he does have some redeeming value. I like to keep an open mind.

A few days later I tooled over to Roland’s headquarters in La Palma, in the heart of the great SoCal sprawl, to have a look at said chopper (on CWs long-term Buell XB12S, a bike I like better and better the cmstier I get). Actually, I knew going in this one was not going to be another goofy made-for-TV chopper even though it actually was made for TV-the Discovery Channel’s “Biker Build-Off” to be specific, the premise of which is you get two work weeks to build a new bike from the ground up and have it judged against a competitor. Roland’s HQ is in fact Performance Machine, a company his dad started in 1970. But before Perry Sands called his outfit Performance Machine, its moniker was Chopper Spring Glide Machine, or some such, which should tell us a lot. With the custom-Hog market explosion over the last decade, of course, a lot of PM’s business now involves custom wheels and other objets de bling. Roland’s title is Designer; outside his office full of cool motorcycle stuff proudly rests his trusty blue TZ, making him really not at all your typical custom-bike builder.

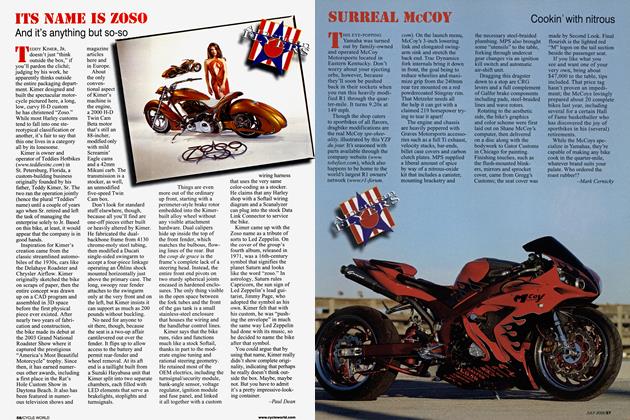

Out in the prototype shop, among the R1 dragster-inprogress and quite a bit of happy banging and yelling, sits “Glory Stomper,” named for the Dennis Hopper biker movie of the same title, circa 1968, that led to Easy Rider. The number 5 on the tail signifies it’s the fifth custom bike built by young Roland, but this one is in fact the sixth. He lost count.

About then it hit me:

Forget architecture. SoCal reflects its history through wheeled vehicles. Paris might have Notre Dame, but then they also have to drive Peugeots and is there even a French motorcycle? Brand-new though it might be, one look at Roland’s bike and its Offenhauser-inspired theme takes you right back to the hopped-up flathead-Ford era that made California the place to be. Glory Stomper started out as a salvaged ’03 Softail, only to have its steering head decapitated down to somewhere under the engine and replaced with a hand-built raked-out front end fabricated by Roland and company from chromoly, along with a custom swingarm. Hard-anodized to look like aluminum, this is actually Roland’s first custom frame but won’t be the last, since building it meant investing in a frame table.

The fuel tank alone looks like it should take two weeks to cobble and then some, but Roland didn’t do it alone. Johnny Chop of Chica’s fame fabricated the steel main chunk, then Roland CNC’ed the scalloped aluminum top from billet. Getting the two to meet up perfectly and bolt together (and hold gas) is one of those things where you just have to scratch your head and wonder how they did it. And though the S&S engine was still being put together at Wink Eller’s shop, the tank fits over it perfectly, too. The finned alloy theme continues in the fabricated oil tank, ignition cover, valve covers, exhaust tip... Roland and crew built everything on the bike save the engine cases, transmission and Öhlins suspenders. Note the TZ axle adjusters out back. Primary drive is via a narrow-belt system PM perfected, which was originally designed by Lil’ John Buttera, whose name I recall from reading Hot Rod in the back row of whatever class that was however many years ago. This bike had to have Wheels of course; these were first machined, anodized, then machined some more before being clearcoated, for a very cool two-tone antique look. The rear is 8.5 inches across, with a 240mm tire that’s wide enough to look right without being too wide to work right.

In contrast to what goes on at many custom bike shops, Roland the Racer builds things to ride hard, and that attitude definitely comes across in the very solid look of the bike. “I’d say it’s not exactly pretty,” says Roland, “more like pissed-off.”

Frankly, it’s not a machine those guys on the Orange

County Chopper TV show could build. Mention them, and Sands’ eyeballs roll back in his head: “Those guys basically go against everything I stand for. It’s not about how much stupid shit you can put on a bike. I like stripped-down form. Really, every bike I build wants to be a racebike.”

It kind of feels that way on a quick blast down the industrial street PM sits on, too. That low handlebar and those highish footpegs don’t exactly say custom Harley. Everything works just like on a real motorcycle: actual suspension, brakes, etc., and you actually could go somewhere on the Glory Stomper, feels like, without the obligatory wannabe-biker-TV chase truck. The balanced/ blueprinted 95-inch S&S motor is in a relatively mild state for reliability. Even so, 95 inches is 95 inches, and Edelbrock heads and a big carburetor in what feels like a light motorcycle means you can scoot right along. It’s surprisingly not even all that loud.

In fact, Roland says he rode the bike all over Puerto Rico, where his Discovery episode was filmed, and even got big air on the Glory Stomper, repeatedly, on a certain driveway near his hotel. “I build them to ride the wee out of them. Is it going to fall apart? No.

I want a bike that, no matter what I do, it can handle it. I don’t want, like, the ladder to fall off the side of my bike and make me crash.” Every part he builds, Roland says, is designed strong and functional enough to work on a GP bike. Even the ladder.

That may be the kind of self-preserving attitude you can only acquire after having broken 29 bones racing GP-style bikes for more than a decade. Cracked ribs, lacerated livers, too, not to mention the recent broken elbow, the result of a skateboarding melee. Though tender of years, Roland has already passed a kidney stone. Creating art means suffering. Bring the pain.

Speaking of pain, Glory Stomper did not win the Biker Build-Off, but then there’s little shame in that since the competition was none other than Arlen Ness, most of whose socks predate Roland. Ness’s Hog even had some sort of belt-driven dohc conversion, just the thing to wow the yokels.

And while it’s an unpopular concept lately, it’s still true that it’s not whether you win or lose, it’s how you play the game. In spite of how things may look on L.A.’s lunar surface, there are people out there who do still value their ancestors and their history, and still appreciate that building a thing is far better than merely buying it. Maybe the coolest part is that Roland is only 30 years old, really a wet-nosed pup among guys known for building custom motorcycles. The kid is just getting warmed up. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGeneration Ten Best

July 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsInfamous Drawer of Useless Dead Weight

July 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCDuty Cycle

July 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2005 -

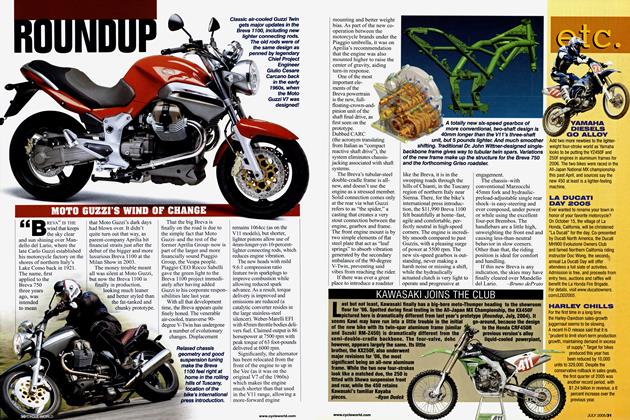

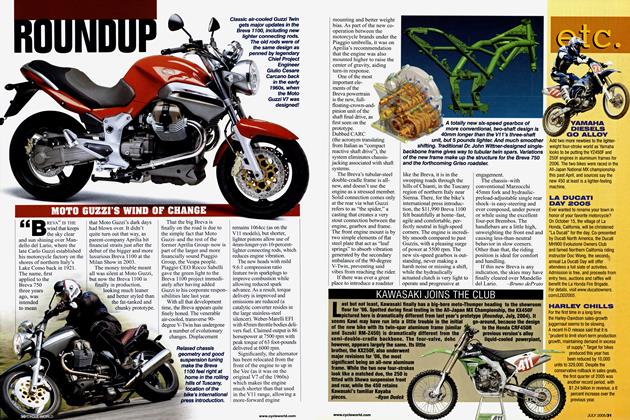

Roundup

RoundupMoto Guzzi's Wind of Change

July 2005 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Joins the Club

July 2005 By Ryan Dudek