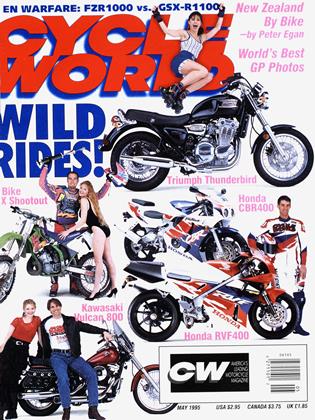

THE WRECK OF THE MYSTERY SHIP

CRAIG VETTER'S FORGOTTEN MOTORCYCLE

DAVID JOHNSON

THIS IS A STORY OF DREAMS-DREAMS COME TRUE, dreams deferred and dreams abandoned. More than two decades ago, a young industrial designer named Craig Vetter found fame and fortune by designing aftermarket fairings and other touringoriented accessories. He saw needs, and he met them with products that looked good, worked well and were priced right.

A dream come true, it w'ould seem. But in a big country, people dream big dreams. And Vetter’s big dream was to style a whole motorcycle-and he fulfilled that dream more than once in his career.

Vetter’s early-1970s BSA/Triumph Hurricane, (see “Path of the Hurricane, CW, October, 1994) has received much attention as of late, but there is another motorcycle, almost forgotten, in Craig Vetter’s past.

“Ever since 1 designed my fairing,” said Vetter at the bike’s 1980 press introduction, “I have looked forward to the time when 1 could design and produce an entire motorcycle the way I wanted it. An ultimate motorcycle... with all the real parts that make up a racer, plus what it takes to be comfortable on the street. The best of everything. A twowheeled equivalent to Carroll Shelby’s 427 Cobra. I’ve worked towards this moment for over a decade. The result is the best thing I’ve done yet, and I believe it will have a significant influence on the future of motorcycling. It’s called the Mystery Ship.”

Cycle World, in the person of staffer John Ulrich, was there, and our October, 1980, issue reported the answer to the Big Question: Why did Craig Vetter want to become a motorcycle manufacturer?

“It’s important to me to have a place in history,” said Vetter. “I want to be remembered as a person who made a contribution.”

Vetter was already well known for his contributions to the sport, but by this time he had retired from his fairing business. Now. he wanted to be remembered for something different, for the dream he had deferredto design and produce a motorcycle. “I’m interested in building legendary machines,” said Vetter.

Whether a product becomes legendary is decided by the marketplace, where people vote with their wallets-and w ith the currency of desire. Shelby’s 427 Cobra, which offered brute performance, striking styling and exclusivity, is unquestionably a legend, and demand is what made it one, even if much of the demand was from people who could not afford to fulfill their desires.

Demand is also what made the 427 Cobra an investment-if you bought one at the right time, like in 1966. But to define something as an investment calls into play another set of rules, and these rules are very clear. Bottom line, a wise investment is something you can buy low and sell high.

And in 1980 Vetter was apparently as much interested in building an investment as in building a legend.

“What can you do to beat double-digit inflation? Well, you can make wise investments. But how can you make a wise investment in the thing you love, motorcycles? You can buy old bikes, but you can’t ride old bikes,” he said.

Actually you can ride old bikes, as Vetter surely knew, so something else had to make this bike special: Its status as rolling sculpture.

The Mystery Ship was calculated to be not only “an investment that takes the form of a motorcycle” but “a piece of art that you can ride.” Vetter was quoted in another publication as saying, “The bike is very ridable, but I see it mostly as artwork-something that should be looked at, thought about a lot more than it is actually ridden.”

Well, investors don’t buy Fabérgé eggs to make omelets, but most motorcyclists want to ride the bikes they buy, even if it means risking an investment. A bike with garage appeal is swell, but that very appeal creates an itch that only riding can scratch.

So how much of the Mystery Ship was motorcycle and how much was art?

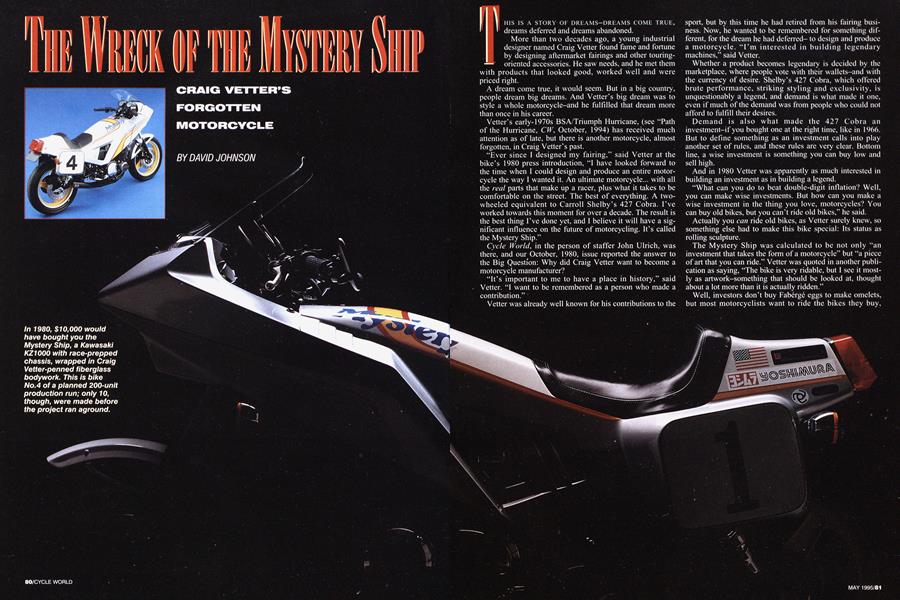

The motorcycle was mostly 1980 Kawasaki KZIOOO, but the Mystery Ship did have race credentials. Its chassis wore many of the same modifications worked out by Pierre DesRoches for Vetter’s KZIOOO Superbike racer of the late 1970s: The stock steering neck was replaced with a new one featuring tapered roller bearings, and it was set at a slightly steeper angle for quicker steering; bracing was added to stiffen the chassis; the swingarm was boxed for rigidity and notched for tire clearance; the shock mounts were relocated forward to provide more rear-wheel travel. The process of modifying the chassis took two days.

The engine remained stock except for a Yoshimura 4-into1 pipe, although several stages of performance modifications were available from Yoshimura as options-including an R.C. Engineering turbocharger.

The Mystery Ship’s art was in the fiberglass bodywork, which took four days to build, and came stock painted silver and white, with other colors optional. It consisted of two pieces, split just in front of the fuel tank. There was a storage area in the tail area behind the leather-covered, velcroattached seat. Six gallons of fuel resided in a welded aluminum tank beneath the bodywork.

Final assembly took another four days. The fork got air caps and Superbike-style handlebars; Mulholland Force 1 shocks were mounted out back. Three-spoke English Dymag magnesium wheels with Michelin tires replaced the Stockers; the brakes were standard issue except for Ferodo pads. Rearset foot controls, a fairing-mounted halogen headlight and Lockhart oil cooler completed the package.

After Vetter’s decades of building products for the masses, his Mystery Ship seems a strangely elitist turn. In the commercial marketplace, volume of sales is an obvious measure of success. By that measure, Vetter was already a resounding hit. His Windjammer fairings had become so ubiquitous that for all practical purposes the terms “fairing” and “Windjammer” could be used interchangeably-at least until the motorcycle manufacturers followed his lead and

started making purpose-built tourers with frame-mounted fairings already installed. Because the Windjammer could be fitted to almost any motorcycle, almost any motorcyclist could have a touring bike. Even Vetter’s creation of the Hurricane turned out to be a populist accomplishment, for it made a minority idiom-the chopper-available to the masses.

By contrast, the stated appeal of the Mystery Ship was pricey exclusivity. “People have to know that a Mystery Ship costs $10,000,” said Vetter to another magazine. “If you own one, half the value of having it is knowing other people know you spent $10,000 for it.”

This was, essentially, Corvette appeal-status-symbol appeal. But that’s not the same as Cobra appeal. The 427 Cobra’s appeal was not its higher price (in 1966, when it appeared, it cost around twice the price of a ’Vette) but that at the touch of the pedal it could walk the walk rather than just talk the talk. It offered the kind of performance that could test a driver’s skill at a moment’s notice.

Vetter’s Mystery Ship appeared on the scene just about the time the wildly exotic and horrifically expensive Bimotas became available, so when Cycle magazine tested a Mystery Ship, its companion in a comparison test was the Bimota KB 1.

Ironically, the Bimota was closer to being a two-wheeled equivalent to the 427 Cobra-a bare-bones, function-first race vehicle at heart, with a minimum of concessions made to street operation. The Mystery Ship was more like a twowheeled equivalent to a Corvette-a stylish performance-status street vehicle at heart, intended to offer more user-friendly levels of comfort and convenience.

Just as a 427 Cobra would bite a Corvette on a racetrack, the Bimota left the Mystery Ship wallowing in its wake at Willow Springs, despite the Mystery Ship’s racing roots. Perhaps that was because its roots were in Superbike racing, which required a production-based machine. The Bimota’s designers, on the other hand, had been free to build their unique vision of a GP bike around the same Kawasaki engine.

But in everyday street use, the Mystery Ship was far more comfortable than the Bimota, just as a Corvette would make a better daily driver than a 427 Cobra. However, the Mystery Ship was also far less comfortable than a stock KZIOOO Kawasaki, which could be had for about one third the price.

Cycle World expressed some...well, ambivalence about > the notion of a built-to-collect bike. And Vetter himself admitted to CW that he was taking a risk: “I have no way of telling if there are 200 people who will spend $10,000 for a motorcycle,” he said. “This whole thing is very speculative and if 1 couldn’t afford to write the whole thing off 1 wouldn’t have started.”

Risk is a natural part of business, but Vetter went on to admit something truly astonishing, coming as it did from an obviously astute businessman.

“If I make 200 I'll lose my ass,” he said. “There’s no way I can make money on the Mystery Ship. There’s too much time and money invested in it.”

Irony of Ironies! The man who wanted to sell Mystery Ships as “wise investments” had just described his own investment in building them as financial folly.

Vetter never had the chance to discover just how unwise his own investment may have proved. For of the 200 Mystery Ships he planned to build, only 10 came to be, and just seven were sold. The reasons why Vetter's Mystery Ship ran aground are best put in his own words: “In October of 1980, I had decided to take up powdered hang-gliding out here in California and the thing crashed on take-off. I broke both my legs and ended up in a wheelchair for some time and 1 lost interest in the Mystery Ship. Pure and simple, I lost interest in big powerful streetbikes like that.” After the accident, Vetter’s interests turned to producing high-performance wheelchairs.

Judging the Mystery Ship as an investment is difficult. Bikes that are very scarce rarely change hands often enough-or publicly enough-for one to accurately gauge market value. I he only Mystery Ships you are likely to have seen advertised for sale were offered in the summer of 1994 by Vetter himself, on the pages of Walneck's Classic Cycle Trader.

I here were two: No. 8 was a no-miles, never-sold bike, with an asking price of $12,500. No. 9 was specially built for drag racer and hop-up parts entrepreneur Russ Collins; this one featured custom paint, Mitchel spun-aluminum

wheels, and an engine that Collins had tweaked with a turbocharger and other mods. Asking price, $15,000.

If we take No. 8 as a reasonable example, and assume that Vetter got his price, the original $10,000 investment would have yielded $2500 in 14 years. You don’t have to be a Wall Street type to figure that $10,000 parked in a CD at even a measly 2 percent for 14 years would have a greater yield, even without the miracle of compounding interest. But money is simply a means of exchange. You can’t start it up and ride it, nor are you likely to sit in the garage and admire it-unless your name is Scrooge. But nobody ever had the pleasure of riding No. 8, either.

Judging the Mystery Ship as a work of art is harder, more subjective. It is the art of the stylist, where the art is on the surface. The Bimota is art of a different sort, the art of the engineer, for its real beauty is beneath the skin, in innumerable beautifully executed mechanical details. Both bikes are beautiful, but in their own way. Final judgments about beauty belong to the eye of the beholder.

And whether or not you consider the Mystery Ship to be a legendary machine is an even more subjective judgment. Vetter himself has said that building fewer than 50 examples isn’t enough to qualify a bike for a place in history. History, however, has a way of setting its own standards, and only the passage of time allows us to glimpse them.

The Mystery Ship's styling certainly did anticipate attempts by the Japanese manufacturers to integrate a protective fairing with the bodywork of sporting machines. Honda’s technological tour de force 1981 CX500 Turbo was the bike that followed most closely in its wake. Not far behind w^ere the turbo bikes of Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki-all of which w'ere attempts to merge style and rider protection with performance. And this trend, when crossed with the full-fairing style of GP bikes, gave us the look of today’s sportbikes.

You will almost never see a Mystery Ship on the road. But even decades hence you will encounter Vetter’s massmarket fairings-and saddlebags and top boxes and tankbags and Hippo Hands and even his Terraplane sidecars—when you ride. Ironically, it will be those contributions, not the Mystery Ship, not even the Hurricane, that guarantee Vetter a place in history, in our hearts and in our minds. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLove At First Ride

May 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGlowing Inspirational Restoration Messages

May 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Mpg Papers

May 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Storming Standard

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Getting Tubular, Going Raging

May 1995 By Robert Hough