CRAIG VETTER

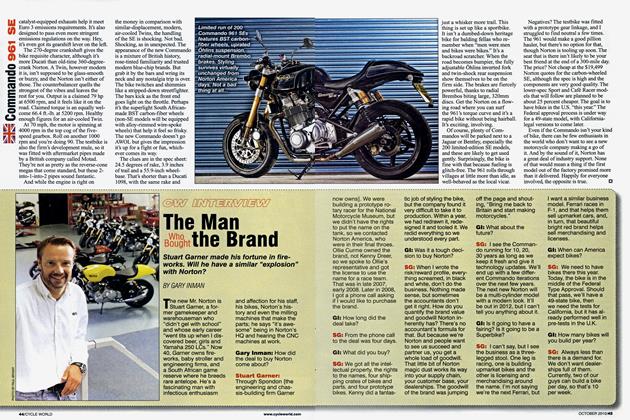

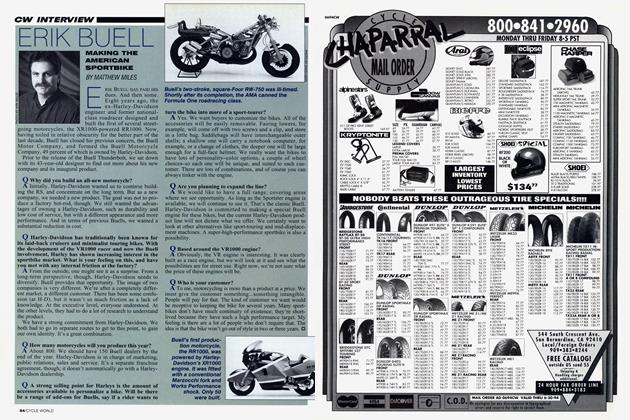

CW INTERVIEW

YESTERDAY THE MYSTERY SHIP, TOMORROW HARLEY-DAVIDSONS?

DAVID JOHNSON

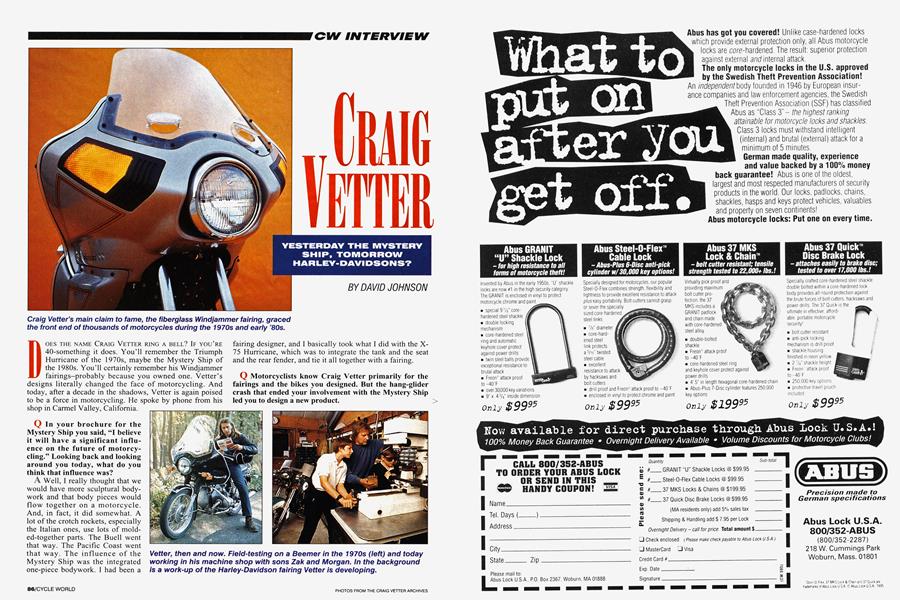

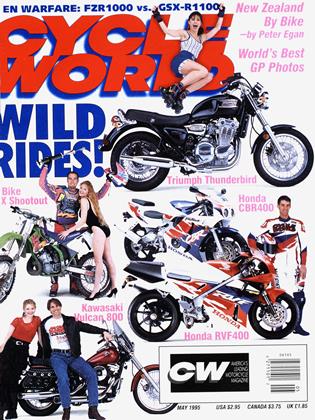

DOES THE NAME CRAIG VETTER RING A BELL? IF YOU'RE 40-something it does. You'll remember the Triumph Hurricane of the 1970s, maybe the Mystery Ship of the 1980s. You'll certainly remember his Windjammer fairings-probably because you owned one. Vetter's designs literally changed the face of motorcycling. And today, after a decade in the shadows, Vetter is again poised to be a force in motorcycling. He spoke by phone from his shop in Carmel Valley, California.

Q In your brochure for the Mystery Ship you said, “I believe it will have a significant influence on the future of motorcycling.” Looking back and looking around you today, what do you think that influence was?

A Well, I really thought that we would have more sculptural bodywork and that body pieces would flow together on a motorcycle. And, in fact, it did somewhat. A lot of the crotch rockets, especially the Italian ones, use lots of molded-together parts. The Buell went that way. The Pacific Coast went that way. The influence of the Mystery Ship was the integrated one-piece bodywork. I had been a

fairing designer, and I basically took what I did with the X75 Hurricane, which was to integrate the tank and the seat and the rear fender, and tie it all together with a fairing.

Q Motorcyclists know Craig Vetter primarily for the fairings and the bikes you designed. But the hang-glider crash that ended your involvement with the Mystery Ship led you to design a new product.

A I cut up the hang-glider and turned it into a wheelchair...then I spent the next two years developing wheelchairs, which gained a whole lot of notoriety outside the motorcycle industry. We won the Boston Marathon with the thing, we got design awards, it was in Time magazine. It got a lot of accolades. But I assumed that if the right wheelchair were made, that...people would get excited and beat a path to the door. Turns out they didn’t. Turns out that when you're in a wheelchair, you don’t get very excited about a wheelchair. Business wasn't very fun, so I stopped that after a couple years.

Q What excites you about today’s motorcycle scene?

A You're speaking to one of the most opinionated people in the world. But you also have to understand that I’m an old guy now. I'm 52 years old. I really have not even looked at it (the motorcycle industry) for about a decade. I sort of lost interest in it. Not because l lost interest in motorcycles, but motorcycles after the Mystery Ship era got too exotic for me. They got more exotic than I was comfortable with. They're just full of little parts. I don't even begin to understand how they all work, and I don't want to pay for the thing if it falls over. I doubt if there’s any Caucasians who understand how to make all those little parts work right. The new motorcycles are exotic, they’re just gorgeous-they’re jewelry, so beautiful and so exotic and so just full of little bits and pieces-but they don't do what I need a motorcycle for anymore. They don’t do anything for me.

In my life I've been happiest on slow, small motorcycles. Probably my happiest motorcycles are things like Bridgestone 90s, the 175 Yamaha. Right now on my ranch, we've got four Honda CTl l()s.

Q At one time, you had quite a collection of motorcycles. We’ve seen many of them offered for sale in various trade publications.

A Yeah, they're gone. You can become a slave to your stuff. If you look out and see stuff that was pristine getting rusty, tires going flat, decals fading, you think, “What am I going to do about this?” What 1 decided to do was sell. 1 kept one of everything that I had: one of every fairing, the Hurricane, the Triumph TT Special, the first Mystery Ship, a fuel-economy bike, my roadracer that I won on at Daytona in 1976, a Rickman Kawasaki. And, of course, the CTl 1 Os and a Yamaha 225 Scrow, my trail bike.

Q We understand you recently purchased a new HarlevDavidson.

A Yeah. I can't speak for the younger generation, but 1 can tell you that for guys in our 40s and 50s, Harleys, for some reason I'll never understand, look just wonderful to us. They look wonderful to me, they look wonderful to a whole lot of males in the world right now. They don't go fast, they don't have to go fast. You can polish it. You can look at it. You can dream. You can just park it and stare at it. You don't even have to ride it. It's enough, just like that. I'm sitting here looking at my turquoise-and-w hite Softail. It makes me feel good just to look at it.

Q Along those lines, we’ve heard rumblings that Craig Vetter is about to re-enter the motorcycle market with a product specifically for Harley-Davidsons. Any truth to the rumors?

A For the last 12 years 1 have focused on being a husband and a daddy...I have a boy who’s 10 and a boy who’s 12. But, yes. I'm back in the motorcycle business, with a project that only a handful of people know about. About a year ago, I found myself sketching a fairing in my notebooks...it got a little farther along and it became clear that 1 was developing and designing a new kind of fairing for Harley-Davidsons...I’ve spent the last year designing this thing for the front of a Harley-Davidson Heritage Softail.

Q if s hard to even imagine a fairing on the Heritage Softail.

A It's got to make a Harley more of what a Harley is. It's got to make your toes curl...There’s no plastic on it. We Harley guys don’t want plastic. It's all metal. It's as good as, and I think better than, anything I’ve ever done...this thing is going to have as much influence-at least on fairings-for the next six or seven years as anything 1 ever did before. It is that different, that radical. And I'm just sitting here in my little workshop in Carmel Valley, all by myself, making it.

I've retained the use of my name...I'm going to be back. It's really nice, because for the last 10 years 1 really haven't wanted to be in the motorcycle business. But I do now. I really am happy with this thing. O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLove At First Ride

May 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGlowing Inspirational Restoration Messages

May 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Mpg Papers

May 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Storming Standard

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Getting Tubular, Going Raging

May 1995 By Robert Hough