GETTING NAKED

CW RIDING IMPRESSION

FROM TAME TO TERROR WITH THE XJRI200

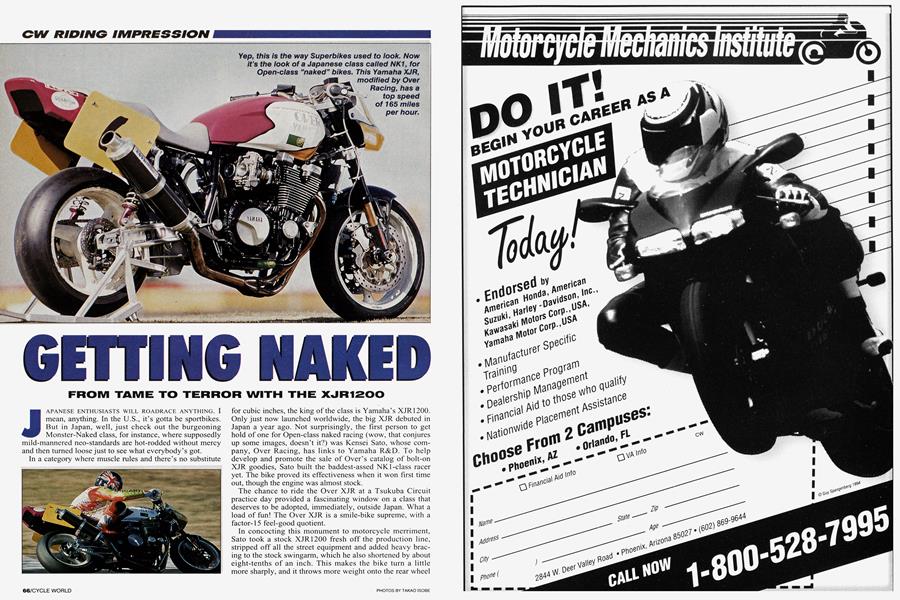

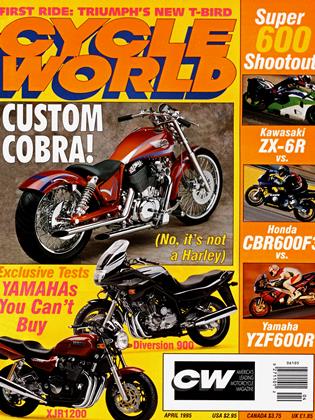

JAPANESE ENTHUSIASTS WILL ROADRACE ANYTHING. I mean, anything. In the U.S., it's gotta be sportbikes. But in Japan, well, just check out the burgeoning Monster-Naked class, for instance, where supposedly mild-mannered neo-standards are hot-rodded without mercy and then turned loose just to see what everybody’s got.

In a category where muscle rules and there’s no substitute for cubic inches, the king of the class is Yamaha’s XJR 1200. Only just now launched worldwide, the big XJR debuted in Japan a year ago. Not surprisingly, the first person to get hold of one for Open-class naked racing (wow, that conjures up some images, doesn’t it?) was Kensei Sato, whose company, Over Racing, has links to Yamaha R&D. To help develop and promote the sale of Over’s catalog of bolt-on XJR goodies, Sato built the baddest-assed NK1-class racer yet. The bike proved its effectiveness when it won first time out, though the engine was almost stock. for added traction. The stock shocks are pitched and replaced by a pair of British-made Quantums. Up front, an Over-modified 41mm Showa upside-down racing fork replaces the conventional front end, with the front ride height dropped 1.2 inches lower than stock and the rear jacked up the same amount. This steepens the steering-head angle in the interest of quicker steering. The Over rearset kit yields extra ground clearance as well as a sportier riding position, but the biggest contribution to the latter is the Over handlebar, two inches narrower than the stock one and 1.4 inches lower. The seat is lowered too, while the stock 12.6inch discs are gripped by four-piston Nissin racing calipers.

The chance to ride the Over XJR at a Tsukuba Circuit practice day provided a fascinating window on a class that deserves to be adopted, immediately, outside Japan. What a load of fun! The Over XJR is a smile-bike supreme, with a factor-15 feel-good quotient.

In concocting this monument to motorcycle merriment, Sato took a stock XJR 1200 fresh off the production line, stripped off all the street equipment and added heavy bracing to the stock swingarm, which he also shortened by about eight-tenths of an inch. This makes the bike turn a little more sharply, and it throws more weight onto the rear wheel

The wheels are from Marchesini, and are purloined from Over’s YZF750 Superbike racer-a 3.50-inch front and 6.25inch rear. These are shod with Bridgestone slicks.

This rejigging of the XJR’s chassis to suit its new life on the racetrack hadn’t been extended to the engine at the time I rode the bike. That meant the air-cooled, 16-valve, dohc Four was still essentially stock. But that’s deceptive, for in this bike, the performance lost when Yamaha detuned the motor from its 123-horsepower FJ1200 sport-tourer guise to the 97 horsepower delivered at 8000 rpm in XJR form has been restored. The primary vehicles for this restoration are Over’s 4-into-l carbon-canned pipe and a set of four 39mm Mikuni TMR flat-slides replacing the 37mm CV carbs fitted for the street.

The engine spins up very freely, picking up revs fast with acres of meaty midrange. The racing-pattern gearchange is very crisp and precise-you can change up without the clutch, no problem-but it’s the wide ratios more than any lack of power that makes the motor feel more like a souped-up streetbike lump than a full-race engine. For this to be a truly effective racing tool, the XJR needs a closeratio transmission.

The TMR Mikunis have a very smooth action without the jerky response of other flat-slides. This made hooking up the rear tire out of Tsukuba’s many slow turns quite easy. The shocks compress slightly as you twist the throttle and the power is transmitted smoothly to the rear end. Over 7000 rpm the engine really pulls hard, up to the 10-grand redline (max revs on the stocker is 9500 rpm). This delivers potent acceleration, though not the type that makes the front wheel reach for the stars out of every turn.

The chassis was what really impressed. You can crank the bike waaay over in turns to take full advantage of the grip from the slicks. This means that you can significantly increase your corner speeds using the extra grip from the loaded front end, while the lower, narrower bars give superbly precise steering and lots of leverage. The steering is fabulous. You can hold the Yamaha around a long sweeper to within a millimeter of your chosen line, feeding in the power as the track opens up. Then you can gun it for the finish line with no fears of the back wheel stepping out.

A big factor here is the fork. It’s especially good under heavy braking, with only a little front dive at first, the big discs stopping the heavy bike reasonably well without any twisting or flexing from the fork. It’s a good thing the Over Yamaha stops well. Caught at 165 miles per hour down Fuji Speedway’s straight, the XJR has speed to spare.

Few bikes I have ridden in the past year were as much sheer fun as the Over XJR. This is mega-biking for the common man-controllable performance with built-in enjoyment, both for the rider and the watcher.

Here’s a bike that breathes a tame sort of fire. It provides spectacular and enjoyable racing at reasonable cost. Come to think of it, wouldn’t this make an ideal support class for the World Superbike Championship? Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDiversion Decision

April 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThinking Small

April 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTool Morality

April 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Rumors Are True! Yamaha's Twin Is In.

April 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Moto' 6.5 Comes Alive

April 1995 By Robert Hough