Burke's Bike

UP FRONT

David Edwards

You DON'T KNOW ED BURKE, BUT YOU do know his bikes. You've most likely ridden one; may have even owned an example or two. At one time, Burke was the most important man in all of American motorcycling.

That time was the late 1970s and early '80s. The bikes were Yamaha Specials, Maxims and Viragos, cruisers all, some of the best-selling bikes America has ever seen-maybe ever will see.

Burke, 25-year-old ex-Sportsman flat-tracker, ex-roadrace tuner, ex-motorcycle dealer, moved from Missouri to California in 1967 to become a district manager for the fledgling Yamaha International Corporation, then in its seventh year of selling bikes in the U.S. By 1973, he had been promoted to the product planning department. This was the post-Easy Rider era, a time of sissybars and extended forks, king-andqueen seats and peanut tanks, apehangers and thick metalflake. Burke took note, then took action.

Being a good corporate player, today he credits teamwork and “listening to what the customer wanted,” but the simple truth is that Ed Burke was the point man in the modern cruiser movement. He jetted to Japan for half the year, working tirelessly, ramrodding final details, making things happen. “It got me divorced,” he says 20 years later. The end result was the 1978 Yamaha 650 Special, based on the standard XS650 parallel-Twin, but with a stepped seat, bobbed rear fender, fat back tire and pull-back handlebars. It took off like a Saturn V booster. Within two years, all the Japanese bike-makers would see the light and have cruisers of their own, but not before Yamaha was selling 30,000 of its 650 Specials a year.

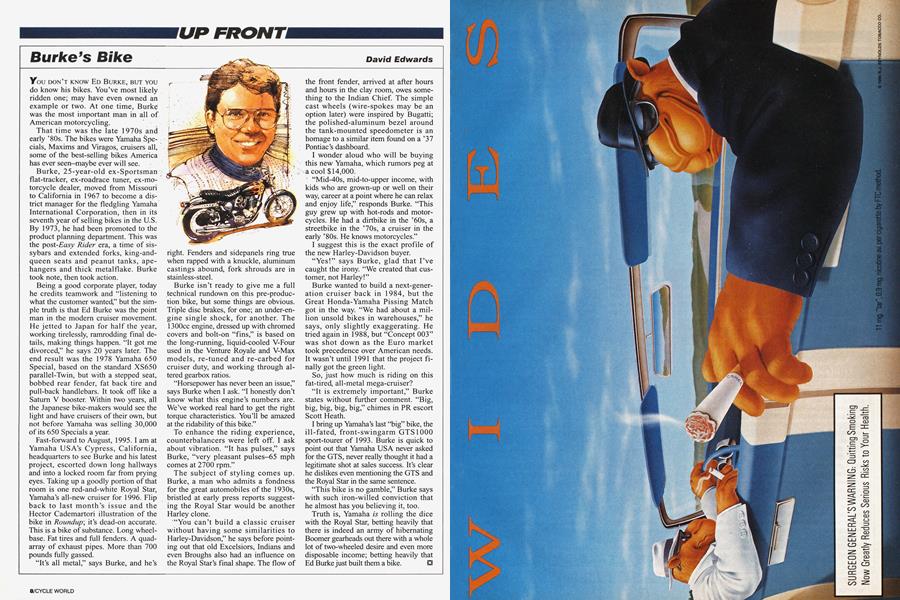

Fast-forward to August, 1995. I am at Yamaha USA’s Cypress, California, headquarters to see Burke and his latest project, escorted down long hallways and into a locked room far from prying eyes. Taking up a goodly portion of that room is one red-and-white Royal Star, Yamaha’s all-new cruiser for 1996. Flip back to last month’s issue and the Hector Cademartori illustration of the bike in Roundup; it’s dead-on accurate. This is a bike of substance. Long wheelbase. Fat tires and full fenders. A quadarray of exhaust pipes. More than 700 pounds fully gassed.

“It’s all metal,” says Burke, and he’s right. Fenders and sidepanels ring true when rapped with a knuckle, aluminum castings abound, fork shrouds are in stainless-steel.

Burke isn’t ready to give me a full technical rundown on this pre-production bike, but some things are obvious. Triple disc brakes, for one; an under-engine single shock, for another. The 1300cc engine, dressed up with chromed covers and bolt-on “fins,” is based on the long-running, liquid-cooled V-Four used in the Venture Royale and V-Max models, re-tuned and re-carbed for cruiser duty, and working through altered gearbox ratios.

“Horsepower has never been an issue,” says Burke when I ask. “I honestly don’t know what this engine’s numbers are. We’ve worked real hard to get the right torque characteristics. You’ll be amazed at the ridability of this bike.”

To enhance the riding experience, counterbalancers were left off. I ask about vibration. “It has pulses,” says Burke, “very pleasant pulses-65 mph comes at 2700 rpm.”

The subject of styling comes up. Burke, a man who admits a fondness for the great automobiles of the 1930s, bristled at early press reports suggesting the Royal Star would be another Harley clone.

’“You can’t build a classic cruiser without having some similarities to Harley-Davidson,” he says before pointing out that old Excelsiors, Indians and even Broughs also had an influence on the Royal Star’s final shape. The flow of

the front fender, arrived at after hours and hours in the clay room, owes something to the Indian Chief. The simple cast wheels (wire-spokes may be an option later) were inspired by Bugatti; the polished-aluminum bezel around the tank-mounted speedometer is an homage to a similar item found on a ’37 Pontiac’s dashboard.

I wonder aloud who will be buying this new Yamaha, which rumors peg at a cool $14,000.

‘ “Mid-40s, mid-to-upper income, with kids who are grown-up or well on their way, career at a point where he can relax and enjoy life,” responds Burke. “This guy grew up with hot-rods and motorcycles. He had a dirtbike in the ’60s, a streetbike in the ’70s, a cruiser in the early ’80s. He knows motorcycles.”

I suggest this is the exact profile of the new Harley-Davidson buyer.

“Yes!” says Burke, glad that I’ve caught the irony. “We created that customer, not Harley!”

Burke wanted to build a next-generation cruiser back in 1984, but the Great Honda-Yamaha Pissing Match got in the way. “We had about a million unsold bikes in warehouses,” he says, only slightly exaggerating. He tried again in 1988, but “Concept 003” was shot down as the Euro market took precedence over American needs. It wasn’t until 1991 that the project finally got the green light.

So, just how much is riding on this fat-tired, all-metal mega-cruiser?

“It is extremely important,” Burke states without further comment. “Big, big, big, big, big,” chimes in PR escort Scott Heath.

I bring up Yamaha’s last “big” bike, the ill-fated, front-swingarm GTS 1000 sport-tourer of 1993. Burke is quick to point out that Yamaha USA never asked for the GTS, never really thought it had a legitimate shot at sales success. It’s clear he dislikes even mentioning the GTS and the Royal Star in the same sentence.

“This bike is no gamble,” Burke says with such iron-willed conviction that he almost has you believing it, too.

Truth is, Yamaha is rolling the dice with the Royal Star, betting heavily that there is indeed an army of hibernating Boomer gearheads out there with a whole lot of two-wheeled desire and even more disposable income; betting heavily that Ed Burke just built them a bike. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsCafe Racing

November 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCExtremes

November 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1995 -

Special Section

Special SectionCalifornia Specials

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

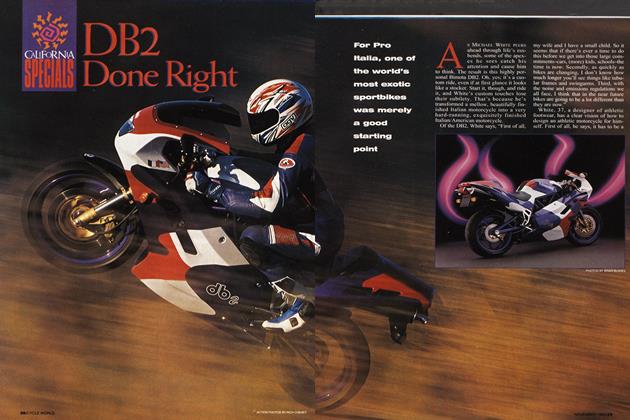

California Specials

California SpecialsDb2 Done Right

November 1995 By Jon F. Thompson -

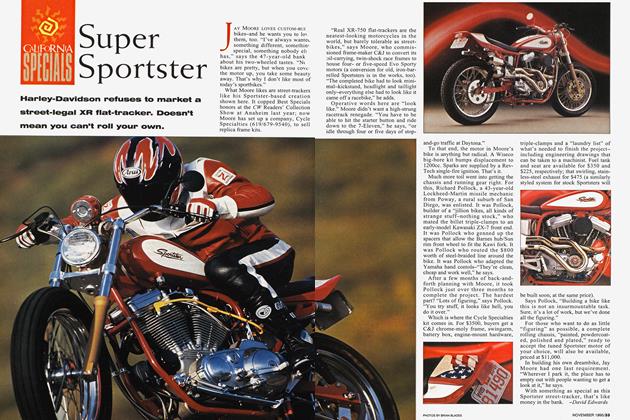

California Specials

California SpecialsSuper Sportster

November 1995 By David Edwards