UP FRONT

David Edwards

Love at first ride

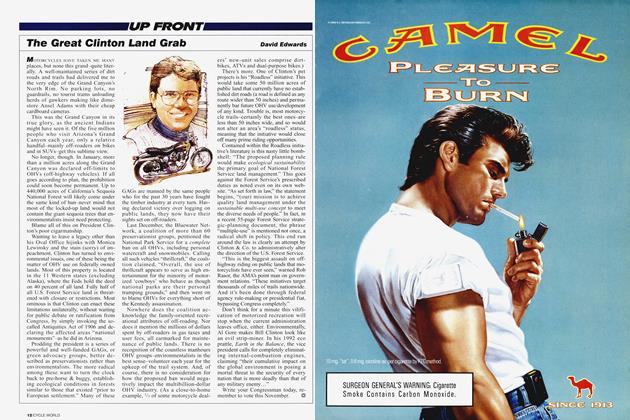

HARD FOR ME TO BELIEVE, BUT IT’S closing in on 25 years since I bought my first streetbike.

I was 15 that spring of 1971, about to graduate from my sophomore year at Thomas Stone High School, but still a good six months away from that holiest of grails, a driver’s license. A strange period, the early-’70s. The Age of Aquarius was in full psychedelic swing, as was the war in Vietnam, but in tiny Waldorf, Maryland, smack-dab in rural, tobacco-growing country, we were pretty isolated from both the weirdness of Haight-Ashbury and the body bags piling up in Southeast Asia. Walter Cronkite and company brought the flickering images of war into our homes each night, of course, but I remember no peace protests nor the names of any local boys among the dead or missing, though I’m sure there were both. Sounds shallow today, I know, but I was more concerned with whether I should go out for the varsity wrestling team in the fall, if Lenora Charpentier even knew I existed, how wide a flare I wanted on my plaid hip-huggers, and, of course, Mrs. Eller, the school’s French teacher, who sent parents’ tongues wagging-not to mention our pubescent boys’ hormones raging-by wearing see-through blouses to class. Our fantasies were further fueled when she came careening into the teacher’s parking lot one day in a new Datsun 240Z sports car, one of the first in the county. But I digress.

What I really wanted back then-besides Mrs. Eller-was a motorcycle.

I'd been riding since I was 12, on minibikes mostly, first those crude Briggs & Stratton-powered affairs, followed by Honda Mini Trail 50s (surely, the world’s most prolific beginner bike), then a Yamaha 90 and a few wrangled rides on the kid-nextdoor's brand-new Honda SL125, a forreal motorcycle.

Obviously, I was ready for a big bike. It would come in the form of a used 1970 Honda CB175 K4, a clean, low-mileage example up for sale because its owner, a Navy man, was shipping out for a tour of duty in the Gulf of Tonkin. I remember the price as $400, raised through my paperroute savings and a loan from my parents. Honda propaganda of the time claimed the 175cc vertical-Twin churned out 20 horsepower at 10,000 rpm, enough to propel it to an alleged top speed of 87 mph (maybe downhill with a tailwind if you believed the overly optimistic speedo).

Cycle World magazine liked the CB175. “The feeling is quite classic as you snick down through the cogs, slowed quickly by a responsive pair of brakes, and then bend it over for a turn, eliciting that sweet four-stroke drone as you dial in a smooth, responsive throttle,” said the editors in a November riding impression. “Just the thing for the beginning rider, or even for the more seasoned road man who likes to...steal away and capture the feeling of what it is like to ride a light Twin over a prettily curving piece of pavement.”

Even today, looking at faded snapshots of my 175, it comes across as a thing of beauty: a two-tone white-andtangerine gas tank that I waxed religiously; graceful megaphone-style exhausts that glinted in the sun; an earnest-looking overhead-cam motor that revved to 10,500 rpm.

Included in the CB’s purchase price was a blue metal-flake helmet and a license plate with 8 months validity left on its registration sticker. The latter turned out to be my ticket to ride. While my younger brother and his friends had to content themselves with spinning donuts in nearby construction sites and vacant lots, I was hustling my Honda down gravel roads that linked up to the county's extensive network of paved farm roads. Freedom!

I racked up something like 5000 absolutely illegal road miles on the CB before I turned 16 and got a license, and never was stopped once. My friend Gary Langley and I even set out twoup for his parents’ cabin on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay one weekend, a round trip of several hundred miles, feeling very much like a pair of young Steve McQueens fleeing from the Germans in The Great Escape.

I learned much in my 18 months of 175 ownership. When it left me stranded in the countryside one day, I learned the value of regular tune-ups, and with instruction from my dad, quickly acquired the skills to set timing, gap sparkplugs, adjust valve clearance, tighten the cam chain and fiddle with fuel-mixture and idle screws. I learned how to lube control cables, how to tighten spokes, how to change tires, how to adjust brakes and how to make a drive chain last.

I also learned about riding from the 175. Perhaps because I was on the lookout for cops, I became very adept at scanning the road ahead, a skill that serves me well to this day. I learned how to hoard momentum on steep downhills like a squirrel gathering acorns, just to make ascending the other side that much easier-I appreciate it all the more today when something like a ZX-11 blasts its way up a mountain pass as if there was no such thing as a steep grade. I learned how to slingshot around corners with the footpegs and centerstand showering sparks, even if the downside of that enthusiasm was also learning that pressing much further levered a motorcycle's wheels plumb off the ground. In that same incident, I painfully learned that riding with your jacket neatly folded and bungeed to your Triple A luggage rack didn’t do much to fight off the ill-effects of road rash.

Most importantly, though, my Honda taught me about the romance of motorcycling, about the joy of taking the road less traveled-both literally and figuratively. Nothing I’ve ever done has had the impact of those first clandestine miles aboard my CB175. A life lesson.

For that, I owe the little bike a huge debt of gratitude. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsGlowing Inspirational Restoration Messages

May 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Mpg Papers

May 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1995 -

Roundup

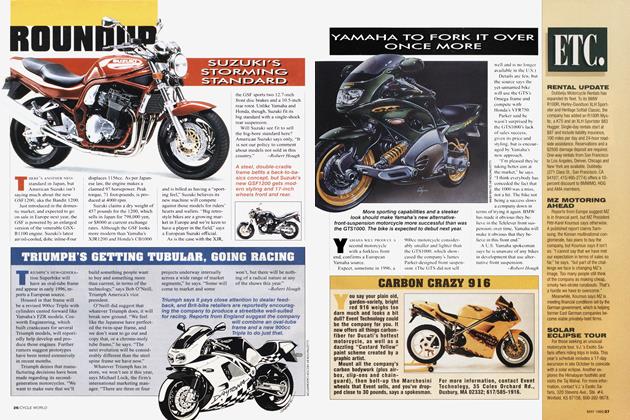

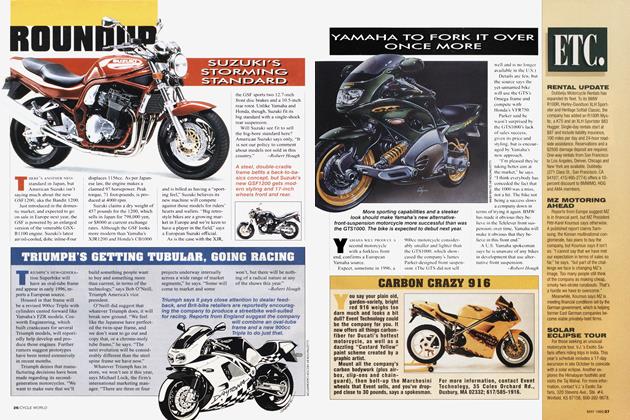

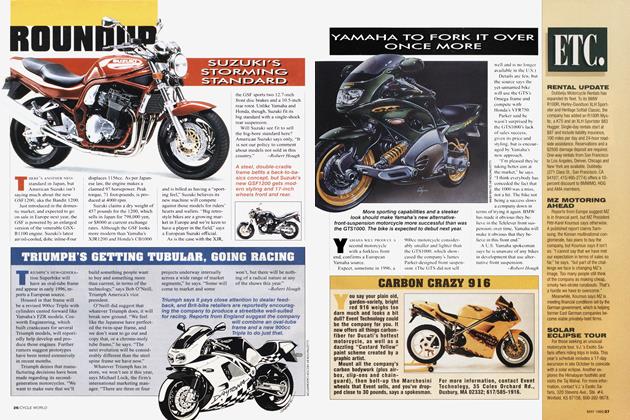

RoundupSuzuki's Storming Standard

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph's Getting Tubular, Going Raging

May 1995 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Fork It Over Once More

May 1995 By Robert Hough