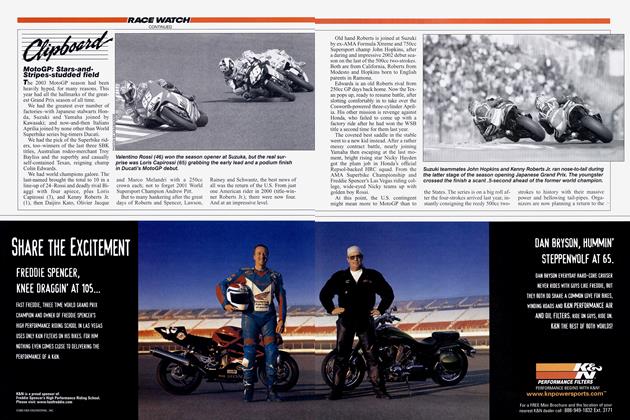

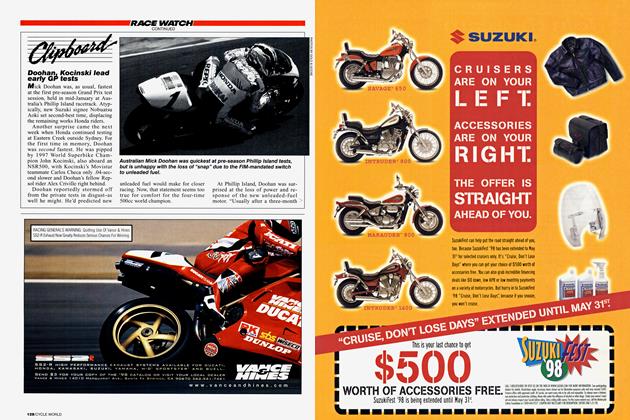

GRAND PRIX CROSSROADS

RACE WATCH

TROUBLE FOR RACING'S BIGGEST LEAGUE?

MICHAEL SCOTT

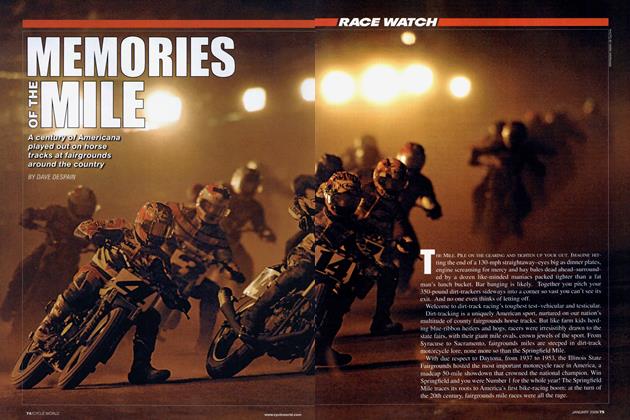

BY MICHAEL SCOTT SOME DESPERATE AND UNCOMFORTABLE QUESTIONS ARE BEING ASKED AT grand prix races lately, questions like these: Whatever happened to the new golden age? Why are we losing, rather than gaining, sponsors? What's the point of racing bikes that bear little relation to the real world? And, perhaps most poignant of all, where have all the spectators gone?

The questions are new because the nature of GP racing was, in 1991, fundamentally changed from the way it had been since 1949, when the Geneva-based Fédération Internationale Motocycliste-the amateur body that sanctions mo torcycle sport-first gathered under one crown the so-called grand prix events in various European countries to create the ultimate motorcycle title. Now, 45 years later, it remains the pinnacle of roadracing, every red-blooded racer’s ultimate target.

Technically the GPs represent a major battleground between three of the Japanese Big Four (Kawasaki opted out after dominating the 250 and 350cc classes but failing to conquer the 500 class in the mid-’70s), enlivened by an increasingly competitive challenge from Italy’s Cagiva. Added spice for ’94 comes from another Italian factory, Aprilia, mounting a giant-killer operation with a lightweight 400cc V-Twin “super250” that will, at least in theory, run rings round the more powerful VFours at some tight circuits. It hardly sounds like a sport, or a business, in crisis. Yet GP racing has never been so precariously balanced.

The political and commercial changes that brought racing to this situation take some unraveling, and that unraveling must begin with a look at the friction between the money men and the sport’s traditionalists.

There had been friction for years. The FIM was, by its nature, remote, high-handed and ponderously slow to react. Meanwhile commercial and TV opportunities were growing rapidly. Various power groups tried to put the world championship on a more businesslike footing, and early efforts crystallized around then-star-rider and always-visionary Kenny Roberts. Fie joined forces with British journalist Barry Coleman to form the breakaway “World Series” of 1980. This madefor-TV closed championship had support from riders, teams and (in a somewhat guarded Japanese sort of way) factories. But it failed to clear the final hurdle when the FIM exerted a stranglehold over the circuits.

IRTA, the International Racing Teams Association, made up primarily of the major works teams but also enjoying support from various smallfry teams, seized control in 1991. Before long, outraged FIM officials were calling IRTA “a bunch of rebels,” and under Road Racing Commission chief Jo Zegwaard, who since has been discredited, mounted a campaign to reduce the influence of the big teams and supposedly bring GP racing back within the reach of less well-funded riders. Zegwaard’s plan was to kill off the two-stroke 500s and bring back MV Agusta-style four-strokes, linked somehow with production machines for privateers. This idea meant that bikes in the top class would be slower than the twostroke 250s. Also, four-strokes are potentially far costlier than twostrokes, if only because of their greater mechanical complexity.

This and other absurdities triggered IRTA into action, and into the arms of Formula One car-racing mogul Bernie Ecclestone, a former motorcycle racer from Britain who took control of F-l after a teams-versus-sanctioning-body battle. He turned it into a multi-million-dollar operation with a huge worldwide TV audience. He seemed just the man to do the same for bikes.

Ecclestone and IRTA had their rebel championship ready to run for 1992. They had the teams, bikes and riders, the tracks, the sponsors and the TV outlets. They only lacked a sanctioning body, and if the FIM wouldn’t play ball, Ecclestone’s car-racing connections gave him some options.

But while IRTA and Ecclestone hatched their plot, the FIM hatched its own. It sold the TV rights of the GP series to Dorna, an influential Spanish TV-rights marketing company partowned by Spain’s Banesto Bank. To Dorna’s considerable alarm, it found it had bought one package and been delivered another.

By the end of it all, with time running short before the start of whichever world championship season was going to happen, Dorna switched sides and entered a partnership with the plotters, who then paid off the FIM to the tune of $52 million over 10 years for all rights to the FIM World Championship. This was about $10 million less than Dorna’s original deal, but still far more than Ecclestone had planned to pay a sanctioning body, and remains a running sore on Dorna’s budget as very difficult economic times continue to choke Europe.

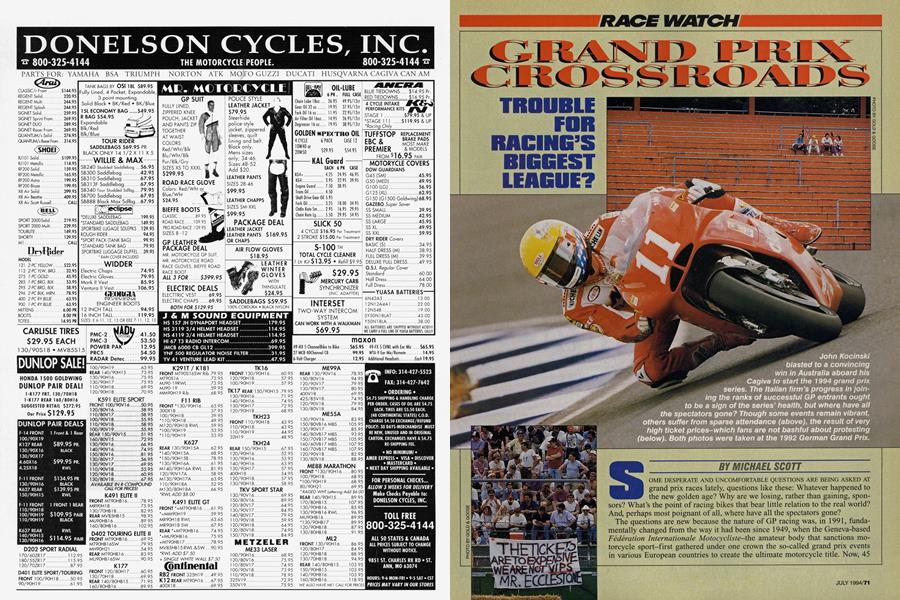

According to Ecclestone’s plan, GPs would attract a new type of eventgoer: champagne sports fans who would mark their national bike GP into their diaries along with the car GP, Wimbledon tennis and the World Cup soccer final. Thus, quite distinct from his management role, Ecclestone became one of several promoters who signed five-year contracts to run newstyle GPs, in his case the German Grand Prix at the Hockenheimring. These promoter contracts have since turned out to be deeply flawed, except in cases where some sort of government backing makes good the inevitable shortfall. For as well as paying a hugely increased fee for the race, generally $1 million, promoters signed away all their rights for sponsorship, track signage and TV. Their only income is from spectators.

Ecclestone’s German GP was among > the events that were especially hard-hit. Ticket prices were doubled as promoters attempted to make their financial nuts; the old crowds stopped coming, and the new well-heeled spectators turned out not to exist. Simple as that. The vast stadium section of the atmospheric Hockenheimring, which a year before had echoed to the enthusiastic roars of capacity crowds, turned instead into row upon row of empty seats.

Ecclestone recognized the writing on the wall before most people. At the start of only his second season, he quietly sold his shares in motorcycle racing to Dorna. He was out. But as a promoter he was locked in, condemned to keep on losing money by the terms of a contract he had negotiated with himself.

Ecclestone remains highly critical of the financial structure of the new regime, and would like nothing more than to be rid of his German GP contract. “The original plan with IRTA would have been much cheaper for promoters, but we ran short of time and were forced to compromise with Dorna,” he explained. This left a topheavy management structure with too many people taking too much money. “What racing needs is a dictator,” Ecclestone added.

He is, by implication, still a candidate for the job. One possible scenario has him selling out profitably to Dorna, watching as it staggers on towards inevitable collapse, then picking up the pieces cheap to restructure the world championship the way he had planned it in the first place. Part of this came uncomfortably close to happening at the turn of the year when the Banesto Bank collapsed. But Dorna-in the short term, at least-disentangled itself from the financial disaster and was last reported fighting off a bid by Reuters, the international news group, to buy Banesto’s 50-percent holding.

The problem remains: Too many chiefs, too little wampum. Certainly Dorna’s executives feel they could run the show without IRTA, while IRTA would gladly get back into bed with Ecclestone, and leave Dorna and the FIM to stew.

The next question concerns the relevancy of the two-stroke GP bikes, and the strength of commitment the factories feel towards them. There are strong links with road-going machines in the 125 class, and to an extent in the 250 class. But the V-Four 500s are a different matter. Real sportbikes are whopping great four-strokes. So what is the point of a factory devoting engineering resources to a commercial irrelevancy? Pure research alone is quite a good reason, and there are others. I recall being much heartened, some six years ago, by the words of Nobuhiko Kawamoto, who has since succeeded the late Soichiro Honda to head Honda Motor Corporation. He enumerated “company spirit” as one important reason for going GP racing. Both these reasons, however, remain on the “luxury” side of any bean-counter’s budget analysis, and in times of recession must be a prime target for the axe.

One curious fact hardly helps the cause of the two-stroke 500s. For the past two years they have been getting slower, rather than faster. Development has somehow peaked, and while there has been enormous developments in improving ridability, so that more riders can circulate at close to lap-record speeds, lap times have failed to improve at several circuits. Since the same problem has not afflicted the 250 class, the smaller bikes are getting uncomfortably close to the big ones at twisty tracks like Eastern Creek and Jerez. This is the reason for the 400cc Aprilia—basically an upgraded 250 that lags in power output (130 horsepower to more than 165) but benefits from a lower weight limit for Twins.

There is a nugget of hope that the big V-Fours will turn out to have relevance after all. It came when Honda introduced programmable electronic fuel injection to its GP race team in 1993. In a world automotive context, the timing could hardly have been better. It coincided with a huge upsurge in interest in two-strokes for cars. Electronic fuel injection combined with some sort of forced induction had turned the smog-making bang-and-pop two-strokes of yesteryear into cleanburning paragons of efficiency, offering strong performance from compact, light and simple engines. Ford, GM, Toyota and Volkswagen are some of the big-time auto-makers who see twostrokes in their near future. With Honda’s fuel injection expected to be followed by Yamaha this year, and surely by the others in the near future, a path of cross-fertilization comes shining into view. Now perhaps the au> tomobile industry will come shopping in the bike world, and all that apparently pointless two-stroke development will suddenly make sense both commercially and morally, even though so far, because of technical differences in their respective systems, there has been no direct bike-to-car technology sharing. But who knows what the future may bring.

That’s assuming the current generation of two-stroke racers have a future. There are other influences that suggest the glorious V-Fours may be living on borrowed time. It may already be very tempting for cash-strapped Japanese factories to switch off this particular stream of development. The 500 GP racers now are almost completely isolated following Japan’s unexpected switch from 500cc GP bikes to a Superbike format for its premier national championship series. The U.S. was one of the first to drop two-strokes as the premier class, which it did as of 1986; Australia has long had a thriving Superbike scene.

In 1990 the FIM dropped the 500 class from the European championships as well, summarily cutting off an important training ground for would-be 500-class GP riders.

The All-Japan Series was the last place a would-be 500 rider could go to learn the business. It was also a highly prestigious series, supported by the factories and heavily sponsored. True, in 1993 these races were contested only by works teams and there were sometimes as few as 10 bikes on the grid. But a new supply of the same privateer Rocand HarrisYamahas that had saved the GP class from a similar fate was about to come on-stream. Instead, the Japanese fed> eration axed the class at the end of 1993. It is hard not to imagine the factories did not connive at least to some degree in this decision.

That may not be the end of the story. After all, other people can also build motors, and the Roc and Harris exercises were a reminder that other people can build chassis, as well. There are several rumors of engine projects, many of them involving Kenny Roberts, who was also highly influential in getting the privateer-chassis effort off the ground. Perhaps isolation will not mean the end of the 500s.

Big-time sponsors still favor GPs, but their numbers are small, and shrunk ominously when Rothmans abandoned Honda in favor of the Williams Formula One car team at the end of last year. The Honda team failed to find a replacement sponsor. Suzuki still has Lucky Strike, Yamaha has Marlboro. European cigarette brands, including HB and Ducados, are still faithful. But these days, tobacco backing poses problems in Europe, with opposition to cigarette advertising putting races like the French GP under serious threat, and imposing “cover-up” paint rules in Britain and Germany. Meanwhile, the smoking moguls have turned their collective gaze to their remaining growth markets in Southeast Asia, the Far East, the former Iron Curtain countries and Latin America, where no such restrictions apply. Perhaps the world championship will be a Pacific Rim series sooner rather than later.

Competition for the dwindling sponsorship pool is acute. The big teams have until now had the lion’s share, but Honda’s experience in ending up unsponsored has sobered everybody. Meantime, others have their eyes on the cash-most especially Dorna, in direct competition for sponsors’ money in one important area and holding a trump card that amounts to a major conflict of interest, especially since the Spanish company now clearly needs to recoup some of its investment over the past two years.

Dorna controls not only the tracksignage rights, but also the TV signal. Thus it can offer the same sponsors guaranteed screen-time via trackside banners, rather than their having to take chances on whether their billboard-bikes will feature heavily in the show or not. Perhaps you’ve noticed the GPs on TV have a heavy emphasis on long shots of the pack coming through a distant corner, and along the straight towards the camera. Strategically placed across the top of the shot is the sponsor’s name. This doesn’t do much for the TV show, especially when you remember that the editors generally have access to excellent, indeed breathtaking, action via onboard cameras. Viewers seldom see it, because there’s no immediate money in it. Meantime, the quality of the show suffers badly at a time when growth of appeal is far more important than the quick buck.

Not everything in GP racing is wrong. The above catalog of doom should be read against a background of a vibrant championship series that still enjoys a number of highly successful and, to be fair, increasingly glamorized meetings. Spain attracts huge crowds to its two races each year; the Ferrari-count among the Italian crowds is always impressive; the Dutch TT at Assen has survived as a major festival of bike racing, drawing huge numbers of fans to a superlative two-wheeler track; TV audiences are on the rise; and while the fat days may be gone, there is still plenty of money wheeling around among the paddock transporters.

So for the moment, at least, GP racing’s problems remain potential rather than acute. Whether they’ll reach that stage and bring suffering and disorder to the sport, or whether they ultimately are solved, remains anybody’s guess. □

British journalist Michael Scott is a long-time GP watcher and one of racing ’s most respected reporters.