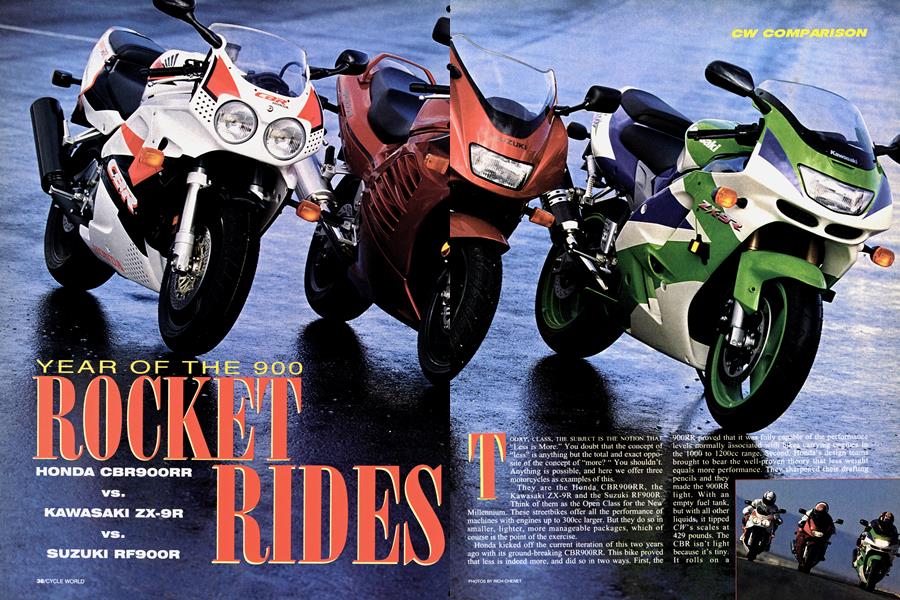

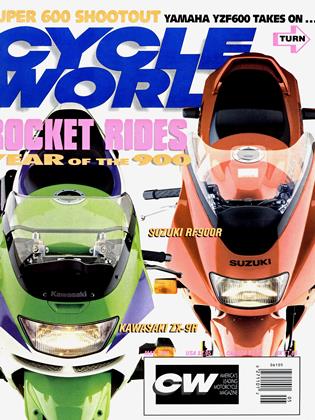

ROCKET RIDES

HONDA CBR900RR VS. KAWASAKI ZX-9R VS. SUZUKI RF900R

YEAR OF THE 900

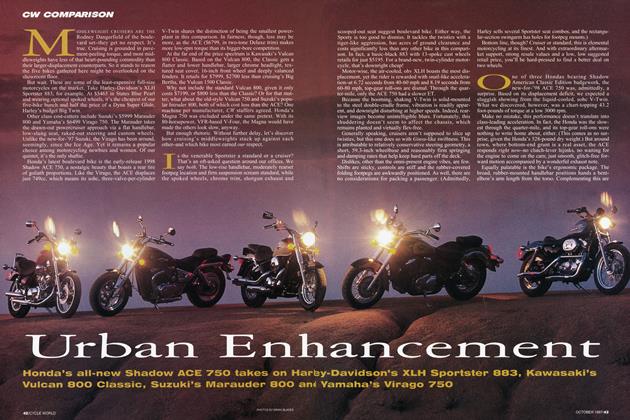

CW COMPARISON

TODAY, CLASS, THE SUBJECT IS THE NOTION THAT "Less is More." You doubt that the concept of "less" is anything but the total and exact opposite of the concept of "more? " You shouldn’t. Anything is possible, and here we offer three motorcycles as examples of this. They are the Honda CBR900RR, the Kawasaki ZX-9R and the Suzuki RF900R. Think of them as the Open Class for the New Millennium. These streetbikes offer all the performance of machines with engines up to 300cc larger. But they do so in smaller, lighter, more manageable packages, which of course is the point of the exercise. Honda kicked off the current iteration of this two years ago with its ground-breaking CBR900RR. This bike proved that less is indeed more, and did so in two ways. First, the

leveT^'rtormally associatd«§H| the 1Ó00 to 120ÜCC range.^Seci brought to bear the well-proÿj equals more performance. Tné

pencils and they made the 900RR light. With an empty fuel tank, but with all other liquids, it tipped CfV's scales at 429 pounds. The CBR isn’t light because it’s tiny. It rolls on a wheelbase of 55.1 inches, after all. It weighs as little as it does because Honda didn’t add material where it wasn’t needed. What isn’t there cannot impede the side-to-side flicks, the hard braking and the elbow-stretching acceleration expected of a sportbike in this class. As a result, the Honda wins Olympic gold in all those disciplines.

The CBR900RR not only is the essence of the less-is-more philosophy, it also is the essence of the Open-class repliracer. Its 893cc engine, which operates at an 11:1 compression ratio and inhales through 38mm flat-slide carbs to produce 114 rear-wheel horsepower, revs with very little flywheel effect. Power production is softest of these three below 7500 rpm, but there’s still enough meat in its midrange that the motor doesn’t have to be spinning a billion, with exactly the right gear selected, to explode out of your favorite comer. As strong as it is, though, the CBR recorded the “slowest” quarter-mile performance of this trio-10.842 seconds at 127.6

miles per hour.

As you use the CBR’s capabilities, you find that it has benefited from some very clever suspension tuning. Its ride quality brings to mind not the harshness you might associate with racebike suspension, rather the plushness of a touring bike. But it’s plushness with control. This is not merely because the bike’s suspension is adjustable-the 45mm cartridge fork for preload and rebound damping, the shock for the same plus compression damping. It’s because the technicians who specified the base spring and damping rates got their sums exactly right. The 900RR is capped with terrific brakes that offer great feel and good stopping power.

The bike makes no bones about what it is. It’s the ultimate hard-core street weapon, right down to the very aggressive riding position it demands. Its pegs are high and back, and its bars low and splayed forward. The bar position seems odd, and earned the wrath of several test riders. But there’s a reason for that position: At very high cornering speeds, the bike begins to feel nervous and front-end-light.

In those situations the CBR becomes as intense as a Superbike, as single-minded as an M-16. Ridden aggressively, then, what’s wanted is the rider to be well forward, placing weight over the front suspension. The Honda is a steel fist in a chainmail glove, and if there’s one thing it does badly, it is coddle its riders. That’s where the competition enters the picture.

If you were Honda’s competitors viewing the success and acceptance of a machine like the CBR900RR, would you seek to copy the bike, or would you do something entirely different? Would you perhaps build an anti-Honda?

An anti-Honda is exactly what Kawasaki and Suzuki both have introduced in the 900cc class for the 1994 model year. But in coming up with a machine completely different from Honda’s, each company also came up with a bike completely different from each other’s.

Where the CBR900RR is light, the ZX-9R (see the detailed preview in the March, 1994, edition of CW) isn’t. It tipped our scales at 501 pounds with an empty fuel tank but with all other liquids. And where the CBR demands a roadrace tuck on the part of its pilot, the ZX-9R doesn’t.

In some ways, the ZX-9R is essentially Kawasaki, and in some ways it isn’t. It is true to its heritage, and to the company’s traditions, in that it produces truly impressive horsepower—a whopping 125 at the rear wheel, enough to blast the bike through the quarter-mile in 10.658 seconds at 130.8 miles per hour, the fastest time from any member of this trio. Its 899cc engine uses Bat combustion chambers and concave piston crowns to produce an 11.5:1 compression ratio, and draws its air-fuel mixture through 40mm carbs and a sophisticated ram-air system not unlike that of the ZX-1 1. This is an engine tuned for peak power. Between 4000 and about 7500, the engine is mellow but ridable. Beyond about 8000 rpm, it’s afterburner-time.

The ZX-9R also is true to Kawasaki’s traditions in that its six-speed transmission is notchy in feel, with long shift throws. Those long throws combine with the lack of feel at the lever of the bike’s hydraulic clutch to induce an especially unfortunate false neutral, all too easily found on backshifts between fourth and third.

Two important characteristics stand out as very different from previous Kawasaki practice. First, the ZX-9R’s Fit and finish is excellent. The quality of the bike’s bodywork, and of its paint and detailing, is fully on a par with that of

Honda, the acknowledged industry leader. Congratulations are in order.

Also most unKawasaki-like is the feel of the ZX-9R’s suspension. Front and rear, this is the most compliant, plush Kawasaki sportbike we’ve sampled in a long, long time. Overall feel from the bike’s suspension systems-a 4lmm cartridge fork adjustable for preload and for rebound and compression damping, and a shock also adjustable for the same parameters—is marvelously controlled. The ride is firm but plush, like that of a German sports car. The inverted 4lmm fork legs are very rigid, so the impressive power and sensitivity of the ZX-9R’s brakes can be exploited to the maximum, even over bumpy comer entrances in racing conditions, with no feel of fork flex. For coming up with a chas sis with this level of excellence, Kawasaki's designers again deserve congratulations.

In keeping with its apparent anti-Honda intent, the ZX-9R feels completely different from the CBR900RR. In spite of its very high performance, once you get past the bike’s race-replica paint job, you find a thoroughly comfortable grand-touring motorcycle that offers a riding position somewhere between that of the ZX-7 and the ZX-11, and a well-padded seat that is complemented by the bike’s carefully calibrated suspension systems.

The ZX-9 lacks the Honda's lightweight feeL Not surpris ing, since its wheelbase is 1.6 inches longer than the CBR's, and the bike weighs a tidy 72 pounds more. Steering effort is highest, and steering feel slowest, of this bunch, and the ZX is sluggish in side-to-side flicks. This in spite of its relatively steep 24degree steering-head angle-the Honda's also is 24, and the Suzuki's is 24.5 degrees. Trail is a conservative 3.7 inches. Compare that with the Honda's 3.5 inches and you begin to get a sense that the ZX-9R's designers intended for the bike to steer in a deliberate manner while delivering exceptional straightline stability with no tendency whatso ever to wag its head exiting bumpy corners.

The Kawasaki's heaviness and horse power translate to a bit of front-end push and some big-time rear-tire wear when the bike is ridden on a racetrack. Raising the fork tubes 10mm in the triple-clamps reduces the push, but there's not much help for the bike's awesome ability to shred rear tires. With Cycle World tester and World Endurance champ Doug Toland at the controls, the bike lapped 2.5-mile Willow Springs raceway in

1:33.30. The more nervous but more focused Honda lapped at 1:32.68, and the much softer-edged Suzuki did a 1:34.08 lap. So in showroom form, ____________________________ the ZX-9R isn't quite a racebike, but it's close. The Kawasaki's true character is revealed away from the racetrack's hard-core con fines. It rewards its rider with a comfortable seat and riding position and is the only bike of the three to have a fuel gauge. Call it a steel fist in a velvet glove. Suzuki's all-new RF900R is more like a velvet fist in a velvet glove. This newest

Suzuki might be an anti-Honda, but it's also an anti-GSX-R streetbike with the role-in Suzuki showrooms, at least-of filling the sport-touring vacuum created by the departure of

the Katana 1100 from Suzuki's 1994 model line. The RF's engine, canted for ward 19 degrees and used as a stressed member, is based on that of last year's GSX-R1 100. It uses the cases, crankshaft and five-speed gearbox of the GSX-R1 100, but instead of the 1100's bore/stroke of 75.5 x 60.0mm, the 900 uses measurements of 73.0 x 56.0mm to deliver a capacity of 937cc. In a continu ation of the clever mix-and-match engi neering philosophy Suzuki has employed with success over the years, the 900's cylinder head is the same basic unit used on the RF600R, but with larger ports and valves, and with a compres sion ratio of 11.3:1. In keeping with the engine's mission as a producer of broad banded power-a mission fulfilled by production of 118 rear-wheel horsepow er-it is fed by four 36mm carbs, the same units that fuel the RF600R. Because of their position in relation to that of the fuel tank, the carbs are supplied by an electric fuel pump.

That fuel tank-a gallon larger than the one supplying the RF600R-sits atop the same basic pressed-steel twin-spar frame used by the 600. The frame is uprated for 900 power by additional bracing and bracketry, including a different subframe to support the large one-piece seat the 900 uses in place of the 600’s thin two-piece affair. Because the 900’s shock uses a bit more spring and a bit more preload than specified for the 600, the 900’s effective rake is, at 24.5 degrees, one-half degree steeper than the 600’s. The 900 uses an aluminum swingarm instead of the 600’s steel unit, and because it uses a different rear sprocket and a 1 10-link chain instead of the 600’s 108-link chain, its wheelbase is a couple of tenths longer than the 600’s-56.7 inches, or the same as that of the ZX-9R. And at 484 pounds dry, it’s 17 pounds lighter than the ZX.

The Suzuki has even more trail than the ZX-9R-a full 4 inches-but it is, on its stock Dunlops, the lightest and fastest-steering of the bunch, and the most nervous at speed. Ascribe that to the fact that the contour of the Suzuki’s front Dunlop is different from that of the Bridgestones on the other two bikes. Whipping a set of Battlaxs onto the RF900 for our track sessions and raising the fork tubes 5mm increased stability at the cost of steering quickness, and placed it between the Flonda and the Kawasaki in these categories.

Rear suspension is fully adjustable, and the 43mm standard-style cartridge fork is adjustable only for preload. Brakes use a pair of four-piston calipers and a pair of 12.2inch rotors up front, a two-piston caliper and a 9.4-inch rotor out back.

That swoopy bodywork certainly gets the looks from bystanders. Its designer is said to have been inspired toward this look by a visit to an aquarium, where he spent his time watching stingrays glide around their tanks. Whatever the inspiration, the RF900R is a handsome brute.

With a suggested retail of $8099, the RF is a full 1200 bucks less expensive than the Kawasaki, and 900 samolians less than the Honda. That’s good. But perhaps Suzuki should have spent a little more time and money on development, even at the cost of raising its price. First, that fairing may be beautiful, but it looks better than it works. Weather protection is good, but wind buffeting off the windscreen can be a problem for riders over 6 feet tall. Riding position is comfortable otherwise, except for a seat that is a trifle on the firm side for the tastes of some riders. Brakes are nicely powerful, but lacked the lever feel and sensitivity delivered by the other two machines.

The Suzuki’s engine makes lots of power and needs only the five transmission ratios it’s got,

instead of the six ratios of the other bikes. Unfortunately, the gearbox isn’t as smooth-shifting as most Suzuki transmissions, causing one of our testers to quip, “Suzuki must have transferred somebody out of the transmission department.” If so, it needs to transfer that person back in.

You want horsepower and rollon capability? The RF900’s got those things, but in exchange for them, it exacts a toll that is paid in the currency of vibration. The engine is fairly crisp at low rpm, and from 5000 rpm on, pulls like a circus elephant. Indeed, there’s enough power on hand to ship the RF through the quarter-mile in 10.726 seconds at 128 miles per hour. Suzuki technicians say the company used the Katana 1 100’s torque curve as the model for that of the RF900R, and we don’t doubt it. Trouble is, while at lower speeds the engine is very smooth, from 7500 rpm up to about 9500 rpm, it vibrates hard-this in spite of the fact that the cylinder-head-to-frame mounting points are cushioned by rubber. For the comfortable, versatile sporttourer the RF is supposed to be, this is less than ideal.

The action of the suspension could also be better. Even with all preload dialed out of the fork, and with compression and rebound damping backed out of the shock, the ride is harsh. Lighter fork oil would minimize the fork’s overly harsh compression damping, but it would exacerbate its insufficient rebound damping, and of the two values, rebound damping is more important for a streetbike than compression damping. On the positive side, the steering is light and neutral, thanks in part to the Dunlop D203 radiais fitted as standard.

In spite of its suspension harshness, the RF is an easy bike to ride quickly. But if you go too quickly-enter a comer too hot, for instance-you notice things like the lack of feel in the brake lever, the flexibility of the fork when braking over bumps. That didn’t stop the RF from posting its 1:34 lap around Willow Springs, however, plenty quick for a softly focused streetbike capable of long-range two-up use.

Other than that, how’d we like the RF900R? Overall, the bike’s got great looks and terrific mirrors. Its vibration levels and suspension, however, are not terrific, especially for hard riders. Nevertheless, we predict that at its price, the Suzuki will make a lot of friends, particularly among riders who stay mostly on smooth roads, and who appreciate the Suzuki’s torque production.

The Honda, holding the ground at the take-no-prisoners, road-weapon end of the spectrum, is terrific; we’ve all known that for the past two years. If you’re looking for the most intense street-Superbike there is, stop at the Honda shop.

And then there’s the ZX-9R. Comfortable enough and smooth enough to pull sport-touring duty, powerful enough to ripple pavement, poised enough to circulate around a racetrack within a half-second of the acknowledged class hot-shot, this may be the most balanced big sportbike ever, a rocket-plushmobile.

So there you have it. That’s today’s lecture in the philosophy of Less is More. These three bikes prove the conundrum’s viability by providing Open-class performance from engines that sneak in under the lOOOcc line drawn in the actuarial sand by insurance companies. Even better, they cover the spectrum. No matter your tastes or riding style, there’s a bike here for you. Isn’t philosophy, and technological diversity, wonderful?

HONDA

CBR900RR

$8999

KAWASAKI

ZX-9

$9299

SUZUKI

RF900R

$8099

View Full Issue

View Full Issue